The New Frontier of Liquid Biopsy: How Blood Exosomal (EV) Proteomics Is Advancing Early Disease Diagnosis

Liquid biopsy has reshaped cancer diagnostics by enabling the non-invasive detection of tumor-derived signals in blood. For years, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) have been the primary focus. However, their performance in early-stage disease remains constrained: when tumor burden is low, ctDNA abundance often falls below detection thresholds, limiting sensitivity. This has accelerated interest in extracellular vesicles (EVs), commonly referred to as exosomes.

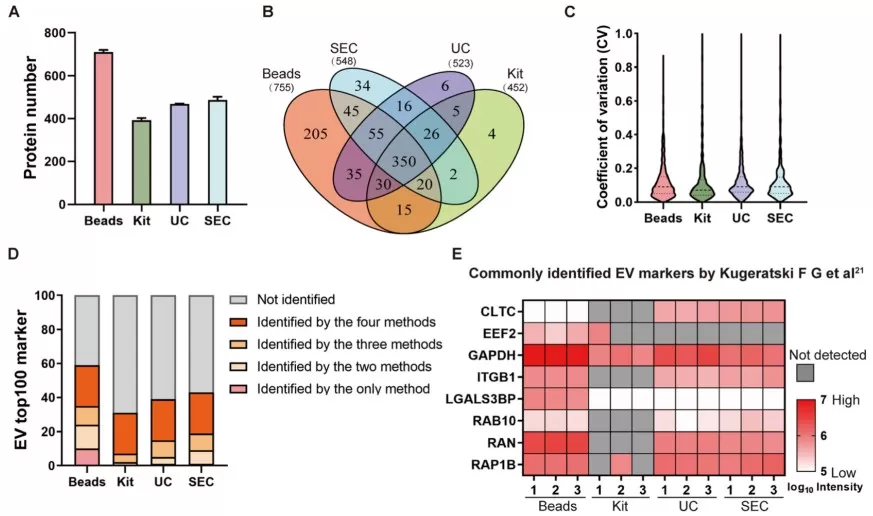

EVs are nanoscale, membrane-bound particles secreted by cells. They transport a diverse molecular payload—including proteins, RNAs, and lipids—and thereby capture “snapshots” of the physiological or pathological state of their cells of origin. Unlike ctDNA, which reflects genomic alterations, EV proteins report on ongoing cellular programs and functional activity in near real time. This makes EV proteomics particularly compelling for detecting diseases such as cancer at stages when clinical symptoms are absent. In this article, we explore the emerging landscape of EV proteomics, its role in early diagnosis, key methodological challenges, and future directions informed by recent scientific progress.

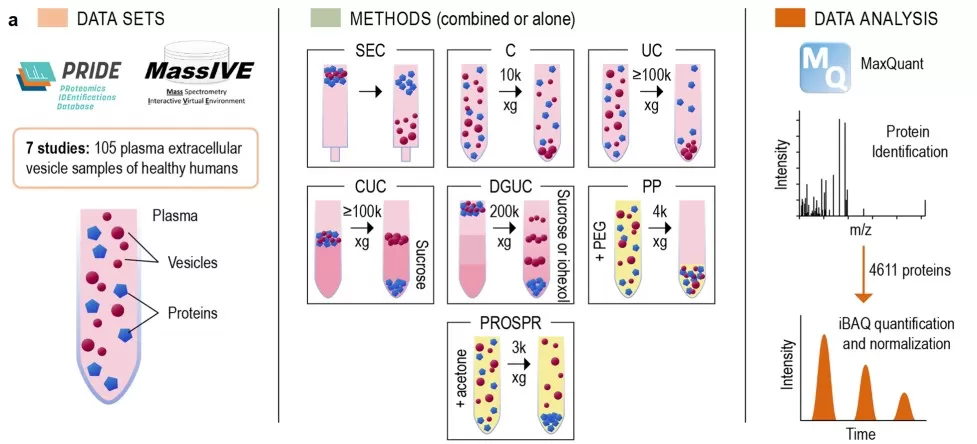

Why EV Proteins, Not Just Plasma Proteins?

A central challenge in plasma proteomics is the extreme dynamic range of blood proteins. Highly abundant proteins (e.g., albumin and immunoglobulins) dominate the sample matrix, frequently masking low-abundance biomarkers that may indicate early disease. This unfavorable signal-to-noise ratio can obscure subtle but clinically relevant protein changes.

EVs offer a strategic advantage because they act as endogenous “information carriers,” selectively packaging proteins that reflect cellular pathways and disease-associated phenotypes. EV membranes, for example, often contain functional surface proteins such as CD47 and ITGB1 involved in intercellular communication; these can become enriched under pathological conditions, including cancer, providing a more disease-relevant biomarker source [1].

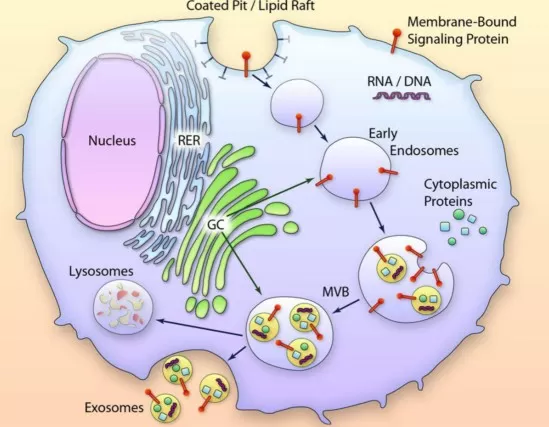

Exosome formation

Why concentrate on EVs specifically?

Reduced complexity relative to whole plasma. EV proteomes are generally less dominated by a few high-abundance plasma proteins because vesicles selectively package proteins depending on cellular origin and disease context. This selectivity supports the identification of coherent disease signatures—for example, a 10-protein panel enabling colorectal cancer detection—that might otherwise be diluted in bulk plasma proteomics [2].

Improved molecular stability. Encapsulation protects EV cargo from enzymatic degradation, supporting reliable downstream analysis.

That said, EV proteomics must address a critical technical confounder: contamination. Plasma-derived EV preparations can be mixed with lipoproteins and protein aggregates, which may mimic EV signals and generate false biomarker discoveries. Meta-analyses of public proteomics datasets have underscored the importance of separating bona fide EV proteins (e.g., proteins clustering with canonical EV markers) from likely contaminants to refine the “true” EV proteome and reduce misinterpretation [3]. In short, EV proteomics provides a clearer view of disease biology—provided the purification and analytical lens is sufficiently clean.

Beyond Genes: Why Proteins?

ctDNA captures genomic alterations—what may be aberrant in a cell—whereas proteins describe what is functionally occurring in real time. As the direct executors of biological processes, proteins drive signaling, metabolism, immune modulation, and cellular interactions. For early diagnosis, this functional layer is particularly valuable because proteomic perturbations can precede overt clinical manifestations and mirror active disease mechanisms.

Evidence across tumor types supports this point. In breast cancer, EV proteins such as TALDO1 have been associated with metastasis and invasion, offering prognostic and mechanistic insight that DNA-centric assays may not provide [4]. In pancreatic cancer, EV proteins including PDCD6IP and RUVBL2 correlate with tumor presence and aggressiveness, delivering an actionable readout of disease activity and progression [5].

This functional dimension matters clinically: a ctDNA assay may detect a mutation, but it cannot determine whether the tumor is actively proliferating, remodeling its microenvironment, or evading therapy. EV proteomics helps bridge this gap by capturing dynamic changes in vesicular protein cargo across disease states, including the enrichment of metastasis-associated proteins in advanced cancers [4]. Accordingly, EVs can be viewed as “protein intelligence packages” that transport decision-relevant biological information for earlier and more informed intervention.

From Blood to EV Protein Signatures: What Does the Workflow Look Like?

For EV proteomics to become clinically deployable, workflows must be standardized, scalable, and reproducible. A representative pipeline typically includes the following stages:

EVtrap isolation of extracellular vesicles

Image reproduced from Bockorny et al., 2024, eLife, licensed under the Creative Commons CC0 public domain dedication.

1) Sample Preprocessing and Standardization

Blood is collected in anticoagulant tubes and processed promptly to isolate plasma or serum, minimizing degradation and pre-analytical variability. Standardization is essential, as differences in collection time, processing delays, and handling can introduce systematic bias. Many studies use cohorts of >100 individuals to ensure statistical power, with samples stored at −80°C to preserve integrity [2].

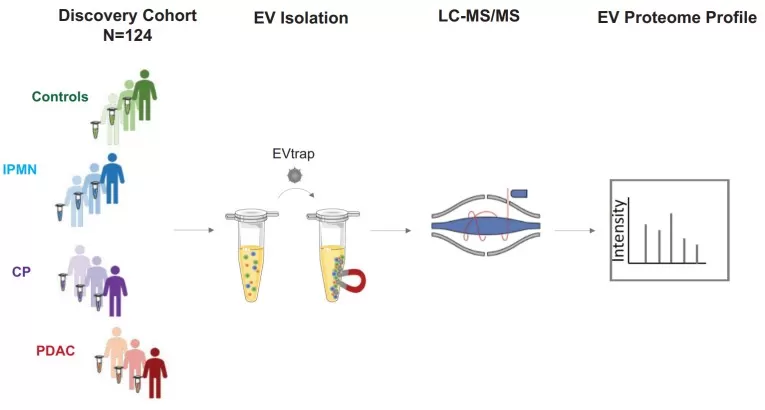

2) EV Isolation/Enrichment

Obtaining sufficiently pure EVs from plasma is often the most technically challenging step. Ultracentrifugation, density gradients, and bead-based capture are commonly used to separate EVs from non-vesicular contaminants. A notable advance is DSPE-functionalized bead capture, enabling direct EV enrichment from plasma within ~10 minutes with high reproducibility, as demonstrated in colorectal cancer studies. Density gradients—validated using proteomics and electron microscopy—can further separate EV-enriched fractions containing markers such as CD63 [2][6]. Without robust isolation, contamination can compromise downstream discovery and validation.

3) Mass Spectrometry Proteomics

Purified EVs are lysed, proteins are digested into peptides, and samples are analyzed using data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry. DIA supports comprehensive and quantitative profiling at scale, enabling measurement of hundreds to thousands of proteins per sample. In breast cancer research, DIA-based EV proteomics identified >800 EV proteins per sample, facilitating diagnostic classifier development [2][4]. High-resolution MS can also reveal biologically meaningful trends, such as depletion of nuclear proteins and enrichment of membrane proteins in exosomes [1].

4) Training–Validation–Blind Testing

Machine learning (ML) models are trained on discovery cohorts to identify optimal diagnostic panels, followed by validation in independent cohorts and blinded testing to assess generalizability. For colorectal cancer, a 10-protein panel achieved 89.3% accuracy for early-stage detection in a blinded validation cohort [2]. This multi-cohort strategy is critical for translating discovery signals into clinically robust assays.

Collectively, this workflow underscores that EV proteomics is not a single experimental step, but a multi-stage system designed to extract biologically meaningful signals from a complex background—where each stage materially affects diagnostic reliability.

Representative Case Studies: How Far Has EV Proteomics Advanced in Early Diagnosis?

EV proteomics has demonstrated strong performance across multiple malignancies, with an increasing emphasis on validation and clinical realism.

Colorectal Cancer (CRC) and Precancerous Lesions: From Discovery to Simplification

A landmark study introduced a streamlined bead-based EV enrichment plus DIA-MS workflow to profile plasma EVs from early-stage CRC patients, individuals with adenomatous polyps, and healthy controls. The study quantified >800 EV proteins and identified dysregulated signatures. A machine learning classifier using only 10 proteins achieved 89.3% accuracy in a blinded validation cohort, supporting feasibility for cost-effective population screening [2].

Performance evaluation of DSPE-functionalized beads to isolate EVs

Image reproduced from Zhao et al., 2024, Chem Sci.

Breast Cancer: DIA Proteomics with Multi-Cohort Validation

In a large-scale study, serum EVs from 126 breast cancer patients and 70 healthy donors were profiled via DIA proteomics. The investigators derived EV protein classifiers capable of diagnosing breast cancer and distinguishing metastatic disease. TALDO1 emerged as a biomarker linked to distant metastasis and was experimentally validated for its role in tumor invasion. Importantly, results were confirmed across five independent cohorts, reinforcing generalizability [4].

Pancreatic Cancer: Large Cohorts and Biomarker Expansion

A study profiling circulating EVs from 124 individuals (including PDAC and benign disease) combined efficient EV isolation with proteomics to identify a 7-protein diagnostic signature (e.g., PDCD6IP, RUVBL2). The panel achieved ~89% prediction accuracy against benign conditions, with additional markers associated with metastasis and poor prognosis. The work also provided an open proteomic atlas to accelerate downstream biomarker development [5].

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA): Precision Diagnostics for High-Risk Populations

Focusing on high-risk cohorts (e.g., primary sclerosing cholangitis), EV proteomics identified diagnostic panels such as CRP/FIBRINOGEN/FRIL for early-stage CCA, achieving AUC values up to 0.947. These markers were validated in total serum and mapped to tumor cell origin via single-cell RNA-seq integration. Machine learning models further supported risk prediction and early diagnosis in both sporadic and high-risk CCA settings [7].

Together, these studies indicate that EV proteomics has moved beyond conceptual promise and is increasingly delivering clinically meaningful accuracy, particularly when paired with rigorous validation design.

How Close Are We to Clinical Early Screening? Key Challenges

Despite rapid progress, several barriers must be addressed for broad clinical adoption:

· Standardization of preprocessing and isolation. Different isolation approaches (e.g., bead capture vs. ultracentrifugation) enrich different EV subpopulations and produce distinct contaminant profiles, limiting cross-study comparability. The MISEV2023 guidelines emphasize stricter reporting requirements and validation steps, including the use of multiple EV markers to assess purity [8].

· Contamination and “pseudo-differences.” Lipoproteins and protein aggregates can be erroneously interpreted as EV biomarkers. Meta-analytic proteomics has addressed this by clustering proteins into EV-enriched versus contaminant-depleted groups, refining the plasma EV proteome and improving discovery specificity (e.g., clusters containing ~71% true-positive EV markers) [3].

Proteomics meta-analysis of plasma extracellular vesicles

Image reproduced from Vallejo et al., 2023, Sci Data, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

· Heterogeneity and rare tumor-derived EVs. In early disease, tumor-derived EVs may be rare and diluted by vesicles from healthy tissues, complicating sensitivity. Potential solutions include immune-capture enrichment for tumor-specific EVs and single-EV analysis to resolve subpopulations [6][9].

· Big data and AI dependence. EV proteomics generates high-dimensional datasets. Machine learning is essential for extracting stable diagnostic patterns and selecting minimal protein panels, as demonstrated in CRC and breast cancer classifiers [2][4].

These challenges highlight that EV proteomics remains an evolving field—but one in which methodological innovation is actively converting bottlenecks into opportunities.

Where the Field Is Going: Targeted Panels, Multicenter Validation, and Multi-Omics

Several trends are likely to accelerate clinical translation:

1. Clinically feasible, simplified protein panels. The field is shifting from broad discovery screens toward targeted panels (typically 10–30 proteins) that can be measured with high-throughput assays. CRC work demonstrates that small panels can retain accuracy when validated under blinded conditions, improving scalability and cost-effectiveness [2].

2. Large cohorts and multicenter validation with DIA. Multi-cohort and multicenter validation is increasingly viewed as a gold standard for generalizability. Breast cancer studies using DIA proteomics across five independent cohorts exemplify this trajectory [4].

3. Standardization and shared community resources. Frameworks such as MISEV2023 and refined EV proteome databases from meta-analysis are helping harmonize methods, reduce contamination-driven artifacts, and accelerate reproducible biomarker development [3][8].

4. Multi-omics integration and functional interpretation. Integrating EV proteomics with transcriptomics and other molecular layers can improve specificity and illuminate mechanism. Multi-omics studies (e.g., in cardiovascular disease) show that paired proteomic and small RNA profiling can reveal disease-modulating pathways and therapeutic targets [6].

Conclusion

EV proteomics is redefining liquid biopsy by unlocking the “protein intelligence” of extracellular vesicles, enabling earlier and potentially more accurate disease detection than conventional DNA-centric approaches alone. From metastatic signatures in breast cancer to simplified panels for colorectal cancer screening, EV-derived proteins function as dynamic reporters of cellular state. While standardization and contamination remain major hurdles, the shift toward focused panels, large-scale validation, and shared community resources is steadily paving the way toward clinical implementation. As these tools mature, EV proteomics may convert a routine blood draw into a powerful window for detecting disease at its most treatable stage.

References

1. Kugeratski FG, Hodge K, Lilla S, McAndrews KM, Zhou X, Hwang RF, Zanivan S, Kalluri R. Quantitative proteomics identifies the core proteome of exosomes with syntenin-1 as the highest abundant protein and a putative universal biomarker. Nat Cell Biol. 2021 Jun;23(6):631-641. doi: 10.1038/s41556-021-00693-y.

2. Zhang J, Gao Z, Xiao W, Jin N, Zeng J, Wang F, Jin X, Dong L, Lin J, Gu J, Wang C. A simplified and efficient extracellular vesicle-based proteomics strategy for early diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Chem Sci. 2024 Oct 15;15(44):18419–30. doi: 10.1039/d4sc05518g.

3. Vallejo MC, Sarkar S, Elliott EC, Henry HR, Powell SM, Diaz Ludovico I, You Y, Huang F, Payne SH, Ramanadham S, Sims EK, Metz TO, Mirmira RG, Nakayasu ES. A proteomic meta-analysis refinement of plasma extracellular vesicles. Sci Data. 2023 Nov 28;10(1):837. doi: 10.1038/s41597-023-02748-1.

4. Xu G, Huang R, Wumaier R, Lyu J, Huang M, Zhang Y, Chen Q, Liu W, Tao M, Li J, Tao Z, Yu B, Xu E, Wang L, Yu G, Gires O, Zhou L, Zhu W, Ding C, Wang H. Proteomic Profiling of Serum Extracellular Vesicles Identifies Diagnostic Signatures and Therapeutic Targets in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024 Oct 1;84(19):3267-3285. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-3998.

5. Bockorny B, Muthuswamy L, Huang L, Hadisurya M, Maria Lim C, Tsai LL, Gill RR, Wei JL, Bullock AJ, Grossman JE, Besaw RJ, Narasimhan S, Tao WA, Perea S, Sawhney MS, Freedman SD, Hildago M, Iliuk A, Muthuswamy SK. A large-scale proteomics resource of circulating extracellular vesicles for biomarker discovery in pancreatic cancer. Elife. 2024 Dec 18;12:RP87369. doi: 10.7554/eLife.87369.

6. Blaser MC, Buffolo F, Halu A, Turner ME, Schlotter F, Higashi H, Pantano L, Clift CL, Saddic LA, Atkins SK, et al. Multiomics of Tissue Extracellular Vesicles Identifies Unique Modulators of Atherosclerosis and Calcific Aortic Valve Stenosis. Circulation. 2023 Aug 22;148(8):661-678. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.063402.

7. Lapitz A, Azkargorta M, Milkiewicz P, Olaizola P, Zhuravleva E, Grimsrud MM, Schramm C, Arbelaiz A, O'Rourke CJ, La Casta A, et al. Liquid biopsy-based protein biomarkers for risk prediction, early diagnosis, and prognostication of cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2023 Jul;79(1):93-108. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.02.027.

8. Zhang Y, Lan M, Chen Y. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV): Ten-Year Evolution (2014-2023). Pharmaceutics. 2024 Oct 29;16(11):1394. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16111394.

9. Martin-Jaular L, Nevo N, Schessner JP, Tkach M, Jouve M, Dingli F, Loew D, Witwer KW, Ostrowski M, Borner GHH, Théry C. Unbiased proteomic profiling of host cell extracellular vesicle composition and dynamics upon HIV-1 infection. EMBO J. 2021 Apr 15;40(8):e105492. doi: 10.15252/embj.2020105492.

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.