Functional Proteomics: The Definitive Guide to Mapping Protein Function and Cellular Mechanisms

In the landscape of modern multi-omics, we have reached a critical realization: the genome is the "blueprint," but the proteome is the "machinery" that executes the work. However, simply knowing which proteins are present—the focus of classical expression proteomics—is no longer sufficient to solve the complex puzzles of drug resistance, disease progression, and synthetic biology.

To truly understand life at a molecular level, we must turn to Functional Proteomics. By shifting the focus from "what is there" to "what is it doing," functional proteomics allows researchers to map the intricate networks of protein-protein interactions, post-translational modifications, and enzymatic activities that drive health and disease. For pharmaceutical companies and clinical researchers, this field is the key to identifying the next generation of drug targets and precision biomarkers.

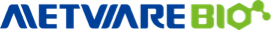

What is Functional Proteomics and Why is it important?

Functional Proteomics is the large-scale, systematic study of protein functions, activities, and regulations. Unlike classical expression proteomics, which quantifies protein abundance (the "inventory"), functional proteomics seeks to characterize the "proteomes in action." This field goes beyond counting molecules to map the dynamic properties of the proteome, including:

1) Three-Dimensional Structures: Understanding how folding dictates function.

2) Subcellular Localization: Mapping exactly where a protein resides (e.g., nucleus vs. cytoplasm).

3) Interactomics: Identifying how proteins form complexes with DNA, RNA, and other proteins.

4) Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): Deciphering chemical "switches" like phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation.

The transition from "Expression" to "Function" represents a significant evolution in systems biology. While a gene might be highly expressed, the resulting protein may remain inactive due to the absence of a specific phosphorylation site or because it is sequestered in an organelle where it cannot reach its substrate. Functional proteomics provides the "context" that expression data lacks. As we move toward 2026, functional proteomics has become the cornerstone of advanced biological research for several reasons:

i. Decoding Complex Disease Mechanisms: It allows researchers to see how signaling pathways are "rewired" in diseases like Alzheimer’s or cancer, even when total protein levels remain unchanged.

ii. Accelerating Drug Discovery: By identifying the active state of a protein, functional proteomics helps pinpoint "ligandable" pockets for new drugs and confirms Mechanism of Action (MoA).

iii. The Bridge Between Genotype and Phenotype: It provides the missing link between our genetic code (genomics) and the actual physical traits or symptoms (phenotype) of an organism.

iv. Enabling Precision Medicine: Functional signatures (such as specific PTM patterns) act as high-accuracy biomarkers that can predict how a patient will respond to a specific therapy, far more accurately than DNA alone.

The proteomics techniques classification.

Image reproduced from Gholap et al., (2023). Proteomics in Oncology: Retrospect and Prospects. In: Kulkarni, S., Haghi, A.K., Manwatkar, S. (eds) Novel Technologies in Biosystems, Biomedical & Drug Delivery. Springer, Singapore.

Functional Proteomics vs. Expression Proteomics: The Difference

When discussing functional proteomics, the concept of expression proteomics naturally comes into play, as the two approaches are often used side by side and complement each other in many studies. Expression proteomics primarily focuses on changes in protein abundance and is a core component of quantitative proteomics, enabling comparisons of protein levels across different biological conditions. However, changes in abundance alone do not necessarily reflect whether a protein is active, modified, or engaged in specific molecular interactions—questions that lie at the heart of functional proteomics. Together, these approaches provide a more complete view of cellular biology: one answers “how much,” while the other reveals “what the protein actually does.” The table below highlights the key differences between expression and functional proteomics.

|

Feature |

Expression Proteomics |

Functional Proteomics |

|

Primary Question |

"Which proteins are present and at what levels?" |

"Which proteins are active and how are they regulated?" |

|

Data Focus |

Relative Abundance: Fold-change in protein concentration. |

Biological State: PTM status, interactome, and enzymatic activity. |

|

Methodological Core |

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with TMT or Label-Free tagging. |

Activity-Based Probes (ABPP), Affinity Purification (AP-MS), and Proximity Labeling. |

|

Sensitivity to Dynamics |

Captures slow changes (e.g., protein synthesis/degradation). |

Captures rapid signaling events (e.g., phosphorylation bursts in milliseconds). |

|

Spatial Awareness |

Usually "bulk" analysis (average of the whole cell/tissue). |

Spatial Proteomics: Mapping function to specific organelles or tissue microenvironments. |

|

Systems Biology Impact |

Provides a static "parts list" of the cell. |

Provides a dynamic wiring diagram of cellular signaling networks. |

|

Computational Burden |

Standard statistical analysis (p-values, heatmaps). |

High-level Network Analysis and AI-driven structural modeling. |

|

Clinical Value |

General biomarker discovery. |

Target identification and Mechanism of Action (MoA). |

Core Pillars and Methodologies of Functional Proteomics

At its core, functional proteomics seeks to answer a fundamental biological question: what are proteins actually doing inside the cell? Unlike approaches that focus primarily on protein abundance, functional proteomics defines protein function through multiple interrelated dimensions. In practice, the functional state of a protein is largely determined by four major parameters: post-translational modifications, protein–protein interactions, enzymatic activity, and spatial localization. Each of these parameters reflects a different layer of regulation, and together they provide a multidimensional view of protein behavior in complex biological systems. Mapping these functional attributes requires specialized proteomic workflows that go beyond conventional expression or quantitative proteomics.

A. Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): The Molecular Switches

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) represent one of the most direct and dynamic mechanisms by which protein function is regulated. Chemical modifications such as phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, and methylation can rapidly alter a protein’s activity, stability, localization, or interaction partners without changing its expression level. For this reason, PTMs are often described as molecular “on/off” switches that enable cells to respond swiftly to environmental cues and signaling events.

In many canonical signaling pathways, including the MAPK and PI3K/Akt cascades, pathway activity is dictated not by the total amount of kinase present, but by its phosphorylation state at specific regulatory residues. A kinase may be highly expressed yet functionally inactive if it is not properly modified. Functional proteomics makes it possible to capture these regulatory events at a systems level, revealing how signaling networks are rewired in processes such as cancer progression, immune activation, or drug response.

Technologically, PTM-focused functional proteomics relies on selective enrichment strategies combined with high-resolution mass spectrometry. Techniques such as immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) or metal oxide affinity chromatography (MOAC) are routinely used to enrich phosphopeptides, while antibody-based or chemical enrichment approaches enable large-scale analysis of ubiquitination or acetylation. When coupled with LC-MS/MS, these workflows allow researchers to identify and quantify thousands of modification sites in a single experiment, providing a global view of signaling dynamics that cannot be inferred from protein abundance alone.

within the mammalian cell._1768355710_WNo_1007d791.webp)

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) within the mammalian cell.

Image reproduced from Dunphy et al., 2021, Cancers, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

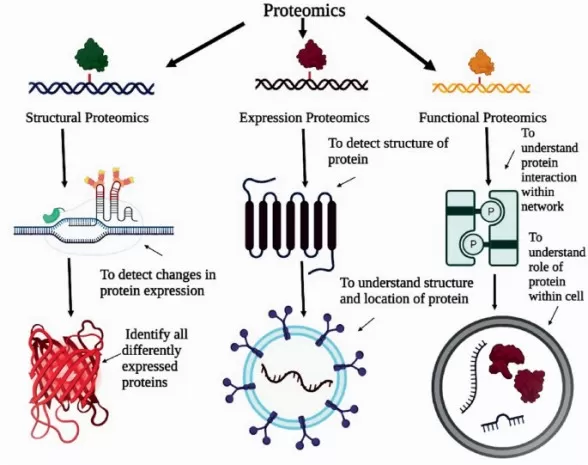

B. Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs): The Molecular Machines

Proteins rarely act in isolation. Instead, they assemble into dynamic complexes and interaction networks that carry out essential cellular functions such as DNA replication, transcriptional regulation, vesicle trafficking, and protein folding. From a functional perspective, understanding who interacts with whom is just as important as knowing how much of a protein is present.

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) analysis is therefore a central pillar of functional proteomics. Mapping the interactome—the complete set of interactions within a cell—provides critical insight into how biological processes are organized and regulated. Disruption of these interaction networks is a hallmark of many diseases, particularly cancer and neurodegenerative disorders.

Mass spectrometry-based methods have become the workhorses of large-scale PPI mapping. Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS) enables the identification of stable protein complexes by isolating a bait protein together with its binding partners. Complementary to this, proximity labeling approaches such as BioID and TurboID capture transient or weak interactions by labeling proteins in the immediate spatial neighborhood of a target protein inside living cells. From a translational standpoint, interactome analysis is also highly relevant for drug discovery, as highly connected “hub” proteins within interaction networks often represent attractive therapeutic targets.

MS-based approaches to studying interactomes.

Image reproduced from Liu et al., 2026, Mass Spectrometry Reviews, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

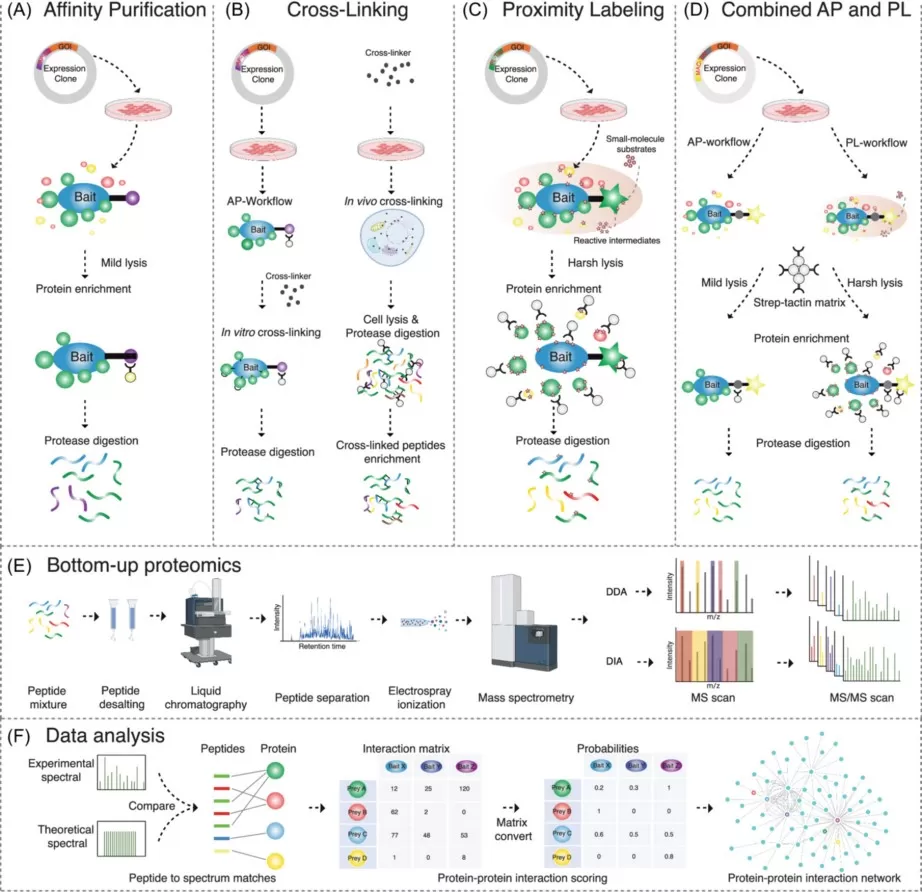

C. Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP): Measuring Enzymatic Function

While PTMs and interactions provide indirect indicators of protein function, enzymatic activity represents the most direct functional readout for many protein classes. Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) addresses this need by using small-molecule chemical probes that covalently bind to the active sites of enzymes in a mechanism-dependent manner.

A key advantage of ABPP is that it distinguishes between active and inactive forms of an enzyme. Unlike antibodies, which typically recognize surface epitopes regardless of functional state, ABPP probes only label enzymes that are catalytically competent. This makes ABPP particularly powerful for studying proteases, kinases, hydrolases, and metabolic enzymes, whose activities are often tightly regulated and poorly correlated with expression levels.

In functional proteomics, ABPP has become a gold-standard approach for linking enzymatic activity to biological phenotypes, drug mechanisms of action, and off-target effects. By combining ABPP with quantitative mass spectrometry, researchers can monitor global changes in enzyme activity across conditions, providing insights that are inaccessible through traditional quantitative proteomics alone.

A model workflow for comparative ABPP.

Image reproduced from Porta et al., 2023, Current research in pharmacology and drug discovery, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

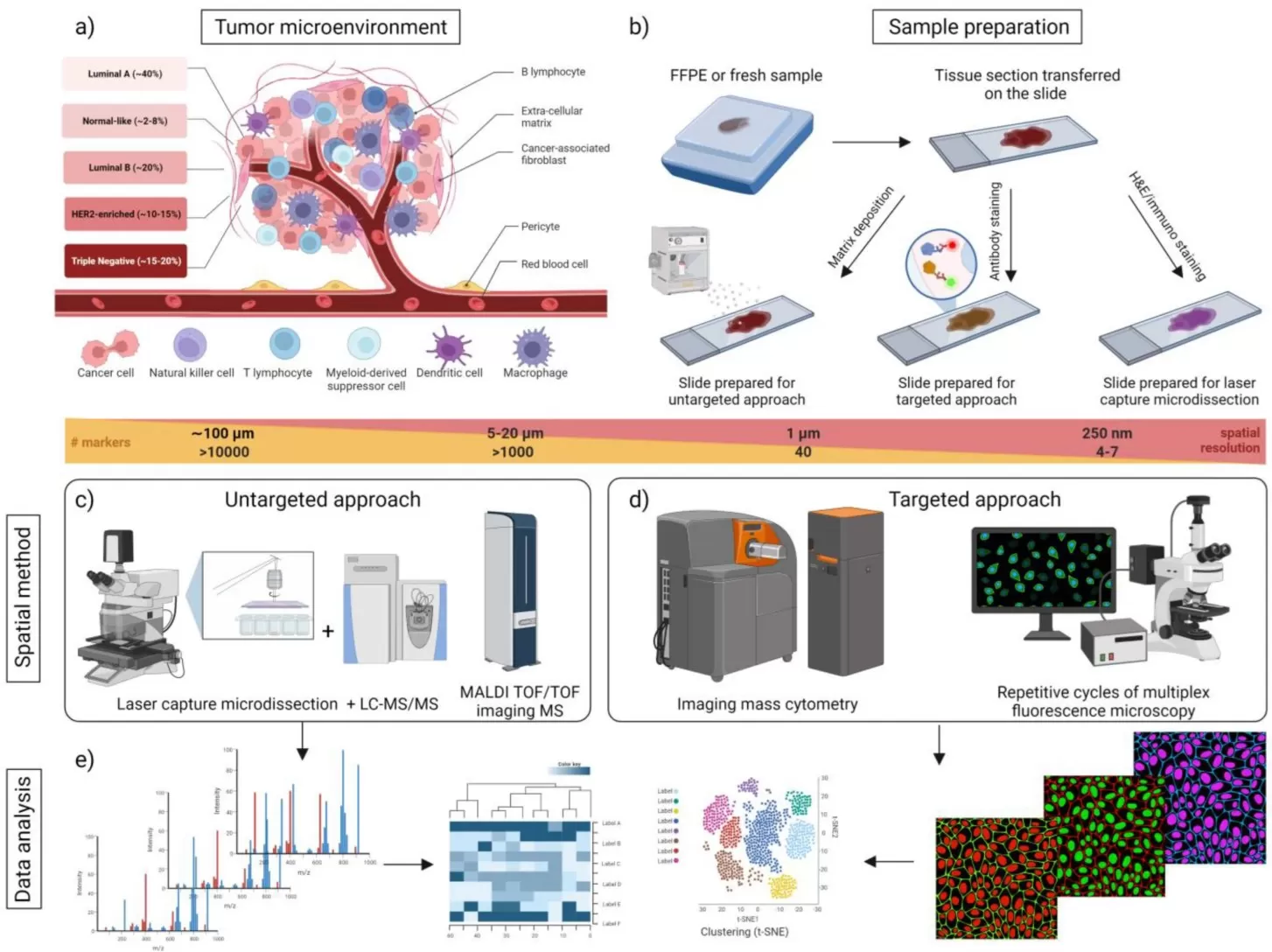

D. Spatial Proteomics: Location Defines Function

Beyond modification, interaction, and activity, protein function is also profoundly influenced by spatial context. A protein’s cellular location often determines whether it can perform its biological role. A classic example is the transcription factor NF-κB, which remains functionally inactive in the cytoplasm but becomes active upon translocation to the nucleus during immune or inflammatory responses.

Spatial proteomics focuses on mapping protein distribution across cellular compartments, tissues, or even subcellular microenvironments. Approaches such as subcellular fractionation followed by mass spectrometry allow quantitative comparison of proteomes from the nucleus, mitochondria, cytosol, or membrane fractions. More recently, imaging-based proteomics technologies, including multiplexed ion beam imaging (MIBI) and Deep Visual Proteomics, have enabled high-resolution, spatially resolved analysis of protein expression and function directly within intact tissues.

By integrating spatial information with PTM, PPI, and activity data, functional proteomics provides a context-aware view of protein function that closely reflects biological reality. This spatial dimension is especially important in complex systems such as tumors, immune tissues, and developing organs, where cellular heterogeneity and microenvironmental cues play decisive roles.

Overview of spatial proteomics approaches in breast cancer.

Image reproduced from Brožová et al., 2023, Proteomes, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

The Functional Proteomics Workflow: From Sample to Insight

Compared with conventional quantitative proteomics, functional proteomics follows a distinctly different analytical logic. Rather than introducing the entire proteome into the mass spectrometer, functional proteomics typically focuses on a defined, functionally relevant subset of proteins, such as modified peptides, active enzymes, or interaction partners. This targeted input strategy allows deeper coverage and higher sensitivity for biologically meaningful events that are often diluted or missed in global protein abundance analyses.

1) Sample Preparation: Functional proteomics begins with careful protein extraction from cell lines, tissues, or clinical biofluids, with particular attention to preserving labile post-translational modifications. The use of protease and phosphatase inhibitors is essential to maintain the native functional state of proteins during sample handling.

2) Enrichment and Targeted Capture: Because functional features such as PTMs or enzyme activity often occur at low abundance, selective enrichment is a defining step of the workflow. Antibody-based approaches, activity-based chemical probes, or affinity matrices are used to isolate specific functional sub-proteomes, such as the phosphoproteome or active enzyme pools.

3) Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Enriched protein fractions are digested into peptides and analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). High-resolution mass spectrometers provide the sensitivity and accuracy required to confidently identify modification sites, interaction partners, or activity-labeled proteins.

4) Bioinformatics and Functional Interpretation: Advanced bioinformatics tools are applied to map mass spectra to protein databases, localize PTM sites, and quantify functional changes across experimental conditions. Pathway enrichment and network analyses then translate these data into biological insight, linking protein function to signaling pathways, cellular processes, and disease mechanisms.

Cutting-Edge Technologies Powering Functional Proteomics

Behind the rapid expansion of functional proteomics lies a convergence of innovations across multiple technological layers. From next-generation mass spectrometry hardware, to advanced data acquisition strategies, and finally to AI-driven computational algorithms, these developments collectively enable deeper, more reproducible, and more biologically meaningful functional protein analysis.

Hardware Innovation: High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS)

At the hardware level, advances in high-resolution mass spectrometry have laid the foundation for modern functional proteomics. Platforms such as the Orbitrap Exploris™ and timsTOF HT deliver exceptional sensitivity, mass accuracy, and resolving power, enabling reliable detection of low-abundance signaling proteins and precise discrimination of subtle post-translational modifications. These capabilities are essential for capturing functional protein states that are often invisible in conventional proteomic analyses.

Acquisition Strategy: Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA)

At the data acquisition level, Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA), including SWATH-MS, has transformed proteomic reproducibility and depth. By fragmenting all ions within predefined mass windows rather than stochastically selecting precursors, DIA proteomics generates comprehensive and consistent datasets with minimal missing values. This makes DIA particularly well suited for large-scale functional proteomics and clinical cohort studies where quantitative robustness is critical.

Algorithmic Intelligence: AI and Machine Learning

At the computational level, artificial intelligence and machine learning are reshaping how functional proteomics data are interpreted. Tools such as AlphaFold2 enable high-confidence protein structure prediction, while deep learning models like Prosit improve peptide identification and intensity prediction from MS data. Together, these AI-driven approaches increasingly allow researchers to predict how genetic variants or point mutations affect protein structure, interactions, and function, directly bridging genomics and functional proteomics.

Biomedical Applications of Functional Proteomics

Functional proteomics has emerged as a cornerstone of translational medicine and biological engineering, moving research beyond simple molecular counting to deep functional interpretation. By integrating high-resolution mass spectrometry with advanced bioinformatics, this discipline is redefining the landscapes of pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and metabolic optimization.

Drug Discovery and Development: Mapping the Ligandable Proteome

In modern pharmaceutical R&D, functional proteomics accelerates the identification of "ligandable" pockets on proteins previously considered undruggable. By utilizing reactive chemical probes, researchers can map binding sites across the entire proteome to pinpoint novel therapeutic targets with high precision. This chemoproteomic approach not only speeds up lead discovery but also elucidates a drug’s Mechanism of Action (MoA) at the molecular level.

In a 2025 study published in Nature Communications, Tian et al. leveraged a library of 70 covalent drugs to screen over 24,000 cysteine sites, creating the first comprehensive proteome-wide ligandability map across diverse chemotypes. The researchers identified 279 high-value novel targets and uncovered functional pockets within proteins that were historically difficult to target. These findings provide a precise roadmap for designing next-generation covalent inhibitors to treat complex diseases like cancer.

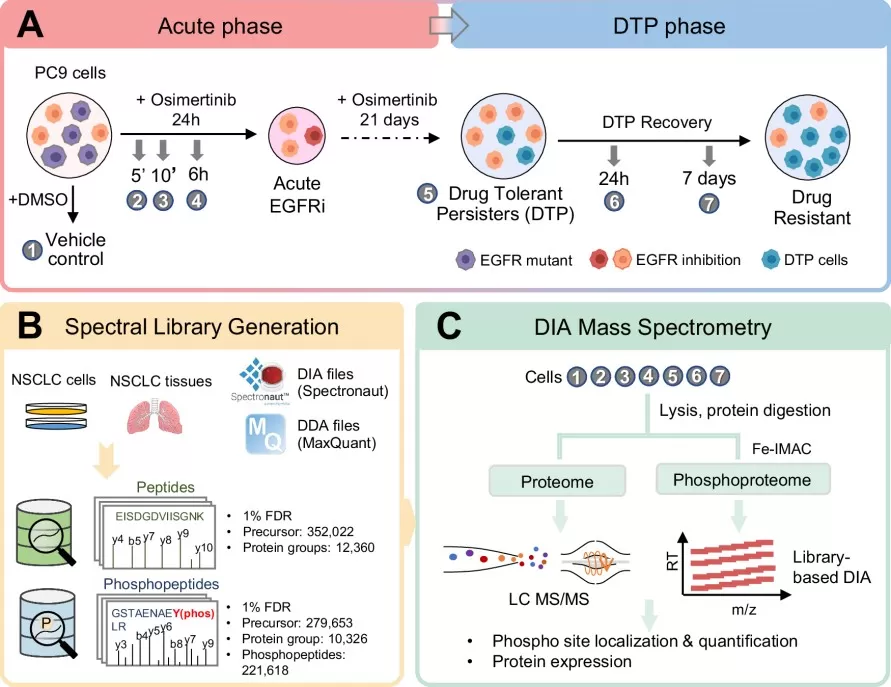

Biomarker Discovery: Decoding Signaling Signatures

Functional proteomics excels in clinical research by capturing dynamic post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, which often predict disease progression more accurately than total protein levels. These "functional signatures" serve as high-sensitivity biomarkers that inform personalized treatment strategies and the early detection of drug resistance. By analyzing clinical samples at the functional level, scientists can identify the specific signaling hubs driving a patient's unique disease phenotype.

In a 2025 publication in Molecular Systems Biology, Hsu et al. employed DIA-based phosphoproteomics to investigate the molecular landscape of osimertinib resistance in lung cancer. They discovered that drug-tolerant persister cells survive treatment by activating a specific CDK1-SAMHD1 signaling axis, which acts as a key driver of acquired resistance. This research identified a robust functional biomarker for predicting treatment failure and demonstrated that combining CDK1 inhibitors can significantly delay the onset of resistance.

Phosphoproteomics DIA analysis workflow.

Image reproduced from Hsu et al., 2025, Molecular Systems Biology, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Synthetic Biology: Optimizing Microbial Factories

Synthetic biology relies on the precise regulation of metabolic pathways, where functional proteomics provides a global view of cellular resource allocation and metabolic bottlenecks. By quantifying protein distribution and enzymatic load across different cellular compartments, researchers can tune microbial factories with the precision of an engineered circuit. This proteome-informed modeling significantly shortens the "Design-Build-Test-Learn" cycle in industrial biotechnology.

Sanchez et al. (2022) demonstrated the power of proteome constraints in optimizing metabolic strategies for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. By developing a whole-cell model (pcYeast) integrated with extensive quantitative proteomics data, the team successfully predicted protein allocation patterns across varying environmental conditions. The study revealed that cellular growth is often limited by functional factors like mitochondrial space, leading to new metabolic engineering strategies that markedly improve production yields.

Challenges and Limitations in Functional Proteomics

Despite its transformative potential, functional proteomics faces significant hurdles that researchers and service providers must navigate to ensure data quality and biological relevance.

Technical Challenges: The "PCR-Gap" and Sample Complexity

Unlike genomics, proteomics lacks a method like Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) to amplify low-abundance proteins. This makes detecting rare signaling molecules or transient PTMs (Post-Translational Modifications) in complex matrices—such as blood plasma—extraordinarily difficult. The dynamic range of the proteome (spanning over 10 orders of magnitude) requires advanced enrichment strategies and ultra-high-sensitivity mass spectrometry to avoid losing critical functional data in the "background noise" of high-abundance proteins.

Biological Complexity: Capturing a Moving Target

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) and enzymatic activities are highly dynamic and context-dependent. A protein’s function in a neuron may differ drastically from its role in a lymphocyte. Capturing these "snapshots" of cellular activity requires sophisticated chemical cross-linking or proximity labeling techniques, yet these methods often struggle to differentiate between stable functional complexes and transient "background" collisions.

Standardization and Reproducibility

Ensuring inter-laboratory reproducibility remains a primary concern for the field. Variability in sample preparation, protease digestion, and MS acquisition parameters can lead to "missing values" in large-scale datasets. Establishing standardized operating procedures (SOPs) and using Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) are essential steps toward making functional proteomics a routine tool in clinical diagnostics.

Future Directions and Innovations in Functional Proteomics

The next decade will see functional proteomics evolve from a specialized research tool into a mainstream diagnostic and engineering platform, driven by three major technological shifts.

Single-Cell and Spatial Functional Proteomics

The most anticipated breakthrough is the shift toward single-cell functional proteomics. While bulk analysis provides an average view, single-cell techniques allow us to understand how functional heterogeneity—such as varying phosphorylation states within a single tumor—drives therapy resistance. When combined with spatial proteomics, which maps protein activity within the native architecture of a tissue, we can finally observe the "molecular conversations" occurring at the cellular interface.

AI-Driven Predictive Proteomics and Multi-Omics Integration

Artificial Intelligence is no longer just for data processing; it is now used for functional prediction. Algorithms like AlphaFold2 are being integrated with MS data to predict how mutations disrupt protein-protein interfaces. The future lies in Multi-omics Integration, where functional proteomic data is merged with transcriptomic and metabolomic layers to create "digital twins" of cellular systems. This holistic view will allow for the predictive modeling of drug responses before a patient even begins treatment.

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications: The Era of Precision Medicine

We are moving toward a future where functional biomarkers—such as the activation state of a specific kinase pathway—will replace simple protein abundance as the gold standard for clinical decision-making. In Synthetic Biology, functional proteomics will enable the design of smarter microbial factories by providing the feedback loops needed to optimize protein allocation and metabolic flux in real-time.

Conclusion: Bridging the Gap from Data to Insight

Functional proteomics represents the ultimate bridge between the static genetic blueprint and the dynamic reality of human disease. By focusing on what proteins do rather than just what they are, this field provides the high-resolution insights necessary to tackle the most complex challenges in drug discovery, clinical diagnostics, and biotechnology.

At MetwareBio, we are committed to providing the cutting-edge mass spectrometry platforms and bioinformatic expertise required to turn these complex functional datasets into actionable biological breakthroughs.

Ready to explore the functional landscape of your samples?

- Learn more about our DIA-MS Services

- Contact us to request a quote for PTM analysis

- Download our demo report on DIA Proteomics

Reference

1. Gholap, A.D., Hatvate, N.T., Khuspe, P.R., Mandhare, T.A., Kashid, P., Gaikwad, V.D. (2023). Proteomics in Oncology: Retrospect and Prospects. In: Kulkarni, S., Haghi, A.K., Manwatkar, S. (eds) Novel Technologies in Biosystems, Biomedical & Drug Delivery. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-5281-6_10

2. Dunphy, K.; Dowling, P.; Bazou, D.; O’Gorman, P. Current Methods of Post-Translational Modification Analysis and Their Applications in Blood Cancers. Cancers 2021, 13, 1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13081930

3. Liu X., L. Abad, L. Chatterjee, I. M. Cristea, and M. Varjosalo. 2026. “Mapping protein–protein interactions by mass spectrometry”. Mass Spectrometry Reviews, 45: 69-106. https://doi.org/10.1002/mas.21887

4. Porta, E. O. J., & Steel, P. G. (2023). Activity-based protein profiling: A graphical review. Current research in pharmacology and drug discovery, 5, 100164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crphar.2023.100164

5. Brožová, K., Hantusch, B., Kenner, L., & Kratochwill, K. (2023). Spatial Proteomics for the Molecular Characterization of Breast Cancer. Proteomes, 11(2), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes11020017

6. Tian, C., Sun, L., Liu, K. et al. Proteome-wide ligandability maps of drugs with diverse cysteine-reactive chemotypes. Nat Commun 16, 4863 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60068-x

7. Hsu, HE., Martin, M.J., Weng, SH. et al. Phosphoproteomics of osimertinib-tolerant persister cells reveals targetable kinase-substrate signatures. Mol Syst Biol 21, 1547–1562 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44320-025-00141-1

8. Elsemman, I.E., Rodriguez Prado, A., Grigaitis, P. et al. Whole-cell modeling in yeast predicts compartment-specific proteome constraints that drive metabolic strategies. Nat Commun 13, 801 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28467-6

Learn more

· Proteomics Quality Control: A Practical Guide to Reliable, Reproducible Data

· Protein Complexes: What They Are and Why They Matter in Biomedical Research

· Blood Proteomics: Serum or Plasma – Which Should You Choose?

· Proteomics and Metabolomics/Lipidomics in Metabolic Disease Research: Insights and Applications

· Mass Spectrometry Acquisition Mode Showdown: DDA vs. DIA vs. MRM vs. PRM

· Proteomics Platform Showdown: MS-DIA vs. Olink vs. SomaScan

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.