Gut Microbes' Chemical Dialogue: How Metabolomics Decodes the "Second Brain" Health Code

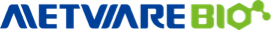

Your gut is home to a microbial ecosystem so vast and adaptive that it is often nicknamed a “second brain.” Trillions of microbes live along the intestinal tract and continuously transform what we eat—together with host secretions such as bile—into thousands of small molecules called metabolites. These metabolites are not just waste. Many behave like chemical signals: they bind host receptors, tune immune activity, regulate barrier integrity, and alter metabolic pathways across the body. When this dialogue stays balanced, these signals help maintain homeostasis. When the dialogue shifts, the same chemical language can contribute to chronic inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and cancer risk [1].

Think of the microbiome as a network of factories. Metabolites are the products and emissions leaving those factories. Your organs—the liver, immune system, adipose tissue, and even tumors—are the city’s infrastructure responding to those outputs. Cataloguing factories is useful, but it does not reveal what is being produced or which products are driving health outcomes. [2,3].

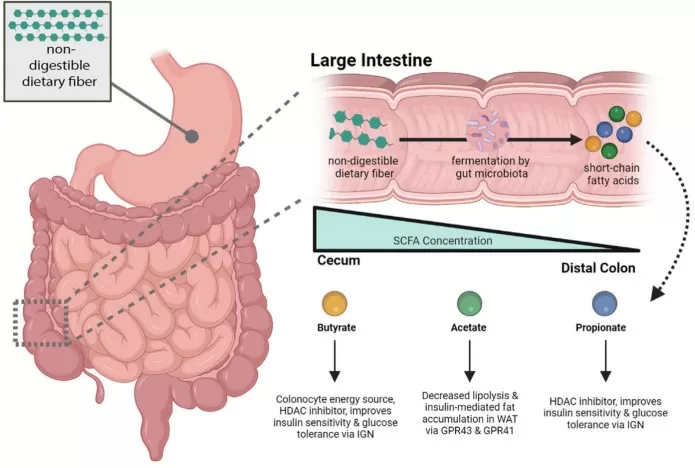

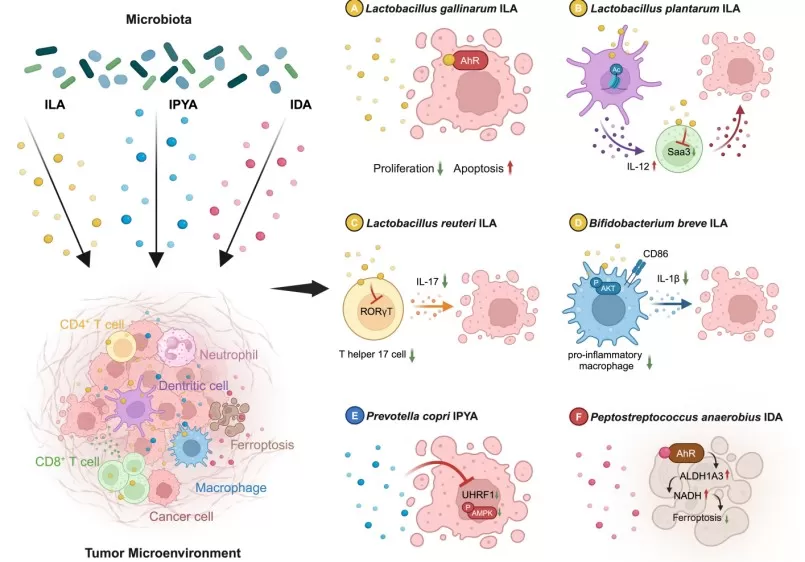

Ways gut microbiota metabolites act on targets

Image reproduced from Liu et al., 2022, Aging Dis, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution.

Why Integrate the Gut Microbiome and the Metabolome?

The limits of microbiome-only profiling

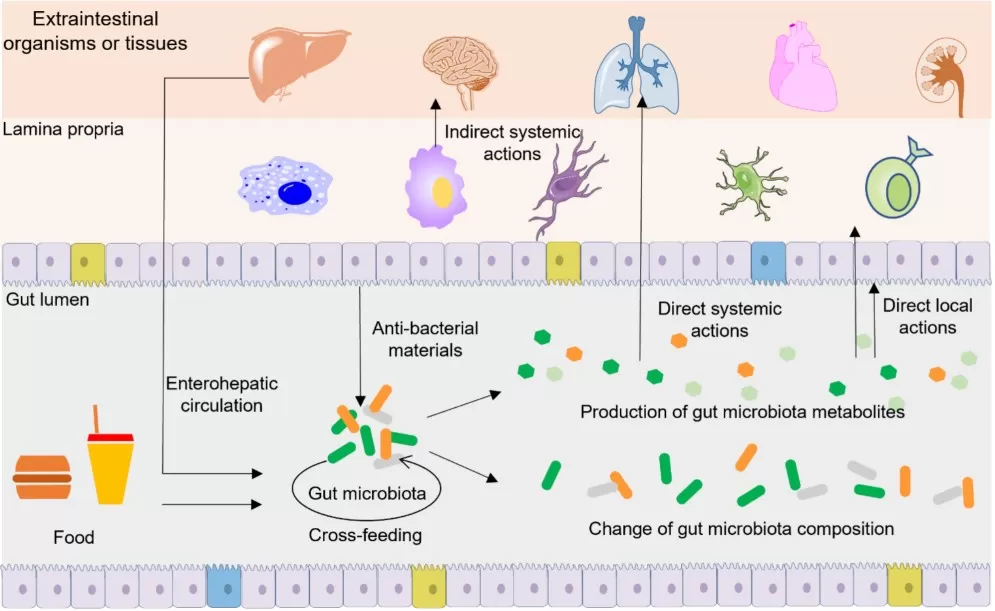

16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomics answer “who is there” and “what genes exist.” But diseases are often driven by function: altered immune signaling, dysregulated inflammation, and rewired metabolic circuits such as impaired insulin signaling. The same taxonomic pattern can lead to different outcomes across individuals because diet, medication exposure, and host genetics change which microbial pathways are active and which metabolites accumulate. This is one reason microbiome findings can look inconsistent across cohorts if taxonomy is treated as a direct proxy for function [4].

Metabolomics as the functional readout

Metabolomics measures the biochemical end products of host–microbe interactions and therefore answers a more actionable question: what physiological changes are occurring right now? Fecal metabolomics reflects the chemical environment in the gut lumen. Plasma or serum metabolomics reports which microbial chemicals (or host–microbial co-metabolites) reach systemic circulation and potentially act on distant organs. Because major signal molecules—short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), secondary bile acids, and tryptophan derivatives—are often co-produced by microbes and host metabolism, the metabolome naturally bridges “microbial potential” and “host phenotype” [2,3].

The synergy advantage: what you gain by combining both layers

When microbiome and metabolome are analyzed together, several practical benefits emerge.

Mechanistic clarity improves. Microbial genes encode metabolic potential, but metabolomics confirms whether a pathway is active and whether its products are accumulating. For example, metagenomes may suggest bile acid conversion capacity; metabolomics can confirm a bile acid pool shift that changes host FXR/TGR5 signaling, with downstream effects on glucose and lipid metabolism [5,6].

Biomarkers become more clinically relevant. Metabolites often sit closer to phenotype and can be measured in accessible biofluids. In colorectal cancer (CRC), an integrated fecal metagenome plus serum metabolome study reported that gut microbiome-associated serum metabolite panels can improve detection performance relative to microbiome-only models, illustrating how “microbial chemistry in blood” can serve as a clinically usable window [7].

Patient stratification becomes more robust. Even if bacterial taxa differ across populations, some microbe–metabolite relationships are reproducible across cohorts. Those stable associations can define functionally similar subgroups and help explain heterogeneity in clinical outcomes [4].

Validation becomes more straightforward. If the data suggest “microbe → metabolite → host pathway,” mechanistic experiments can test each link using strain culture, ex vivo fermentation, metabolite supplementation, or fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). Modern metabolomics pipelines are increasingly designed to support this discovery-to-validation loop [8,9].

gut microbiome metabolome associations

Image reproduced from Muller et al., 2021, Microbiome, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Spotlight Applications: Metabolic Disease and Cancer

1) Metabolic diseases: turning diet into endocrine and inflammatory signals

Obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D), and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD/NAFLD) share core features: insulin resistance, ectopic lipid accumulation, and chronic low-grade inflammation. The gut microbiome sits upstream of these phenotypes because it converts dietary inputs into chemical signals that act on host receptors and metabolic tissues. Microbiome–metabolome integration is powerful here because it can trace a mechanistic chain from diet to microbial metabolism to host pathways [1,10].

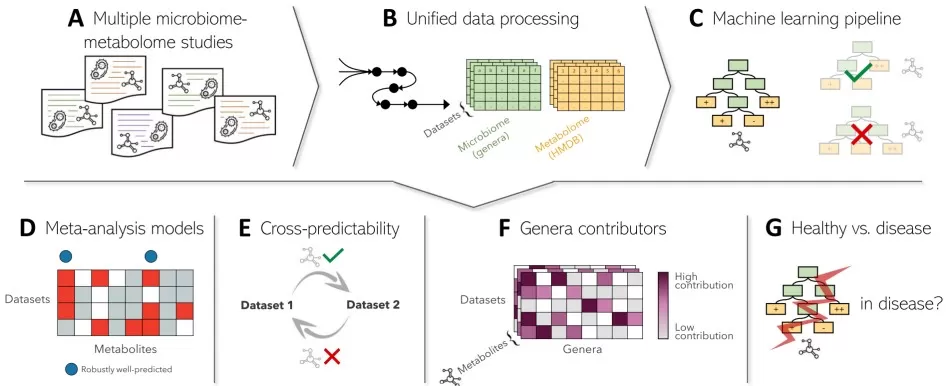

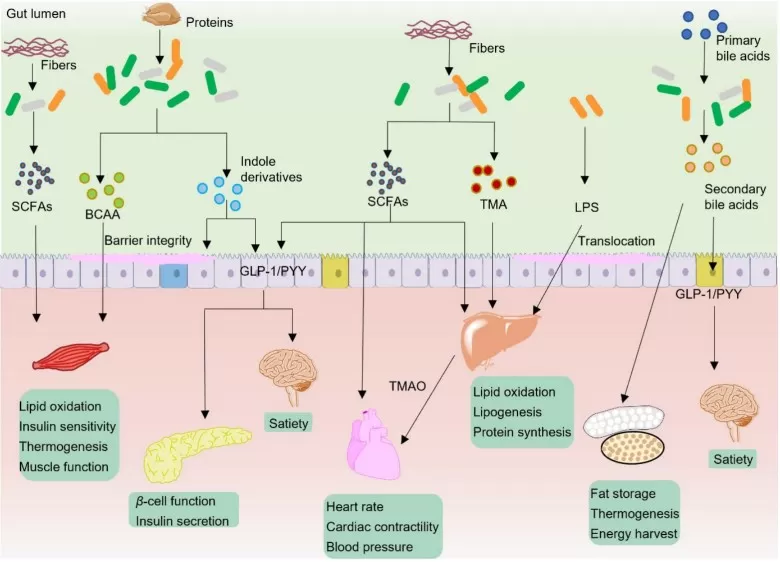

Microbially produced SCFAs and their key effects on host metabolism

Image reproduced from Fogelson et al., 2023, Gastroenterology, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

SCFAs: from fiber fermentation to host signaling

SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate) are produced when microbes ferment dietary fibers. SCFAs can engage G-protein-coupled receptors in the gut and on immune cells, influencing gut hormone secretion (including GLP-1) and inflammatory tone. Butyrate also acts as an epigenetic regulator: as an HDAC inhibitor, it can shift transcriptional programs toward epithelial repair and anti-inflammatory states. These mechanisms matter because barrier integrity and low-grade inflammation are central drivers of metabolic dysfunction: when the barrier is weakened, microbial products can enter circulation and amplify systemic inflammatory signaling, reinforcing insulin resistance [6,10,11].

A key translational point is that SCFAs are not just associations. They offer a direct intervention handle: dietary fiber, prebiotics, or therapeutic delivery strategies can be designed to restore SCFA signaling. Reviews on metabolite-based therapeutics emphasize that “delivering the function” (the metabolite) can sometimes be more controllable than trying to force stable taxonomic shifts in the microbiome [11].

Bile acids: metabolic switches controlled by microbial enzymes

Bile acids are not only detergents for fat absorption; they are endocrine signals. The liver produces primary bile acids, and gut microbes deconjugate and transform them into secondary bile acids, reshaping the bile acid pool that activates receptors such as FXR and TGR5. FXR signaling influences hepatic lipid synthesis, gluconeogenesis, and bile acid homeostasis. TGR5 signaling can modulate energy expenditure and gut hormone release. When microbial bile acid conversion is perturbed, receptor signaling can shift in ways that align with MAFLD/NAFLD and insulin resistance phenotypes [5,6,10]. Changes in microbial steps such as deconjugation and 7α-dehydroxylation can reshape bile acid pools and downstream signaling [5]. This is precisely where multi-omics adds value: microbiome profiling can suggest which taxa or enzymes are present, but metabolomics is needed to confirm whether bile acid pools actually changed in the relevant direction and compartment.

Tryptophan metabolites: controlling mucosal repair and inflammatory set-points

Microbial metabolism of tryptophan generates indole derivatives that can activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), a transcriptional regulator coordinating mucosal immunity and barrier repair. In metabolic disease, this is important because barrier dysfunction amplifies inflammatory signaling. When indole–AhR signaling is reduced, inflammatory cascades can intensify, reinforcing insulin resistance and liver inflammation. Conversely, restoring indole pathways has been proposed as a strategy to stabilize mucosal homeostasis and reduce chronic inflammatory tone [6,12].

2) Cancer: metabolites that shape barrier function, genotoxic stress, and immunity

Cancer biology is shaped by chronic inflammation, epithelial integrity, and immune surveillance—each of which can be influenced by microbial metabolites. In CRC, dysbiosis is frequently linked to altered microbial outputs that affect barrier function and inflammatory tone; more broadly, microbial metabolites are discussed as contributors to heterogeneity in disease progression and treatment response. Microbiome–metabolome integration helps translate “dysbiosis” into concrete chemical mechanisms [13,14].

Indoles and the tumor-adjacent immune landscape

Indole metabolites influence epithelial repair programs and mucosal immunity through AhR signaling. In tumor contexts, this matters because barrier disruption and chronic inflammation promote carcinogenesis. Reviews focusing on microbial indole metabolites in tumors describe how indole–AhR pathways shape cytokine programs and immune-cell differentiation, potentially shifting the balance between inflammatory and regulatory states in ways that influence tumor initiation and progression [12].

Indole metabolites that can act directly on tumor cells

Image reproduced from Jia et al., 2024, Gut Microbes, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Secondary bile acids and oxidative/genotoxic stress

Certain secondary bile acids discussed in CRC contexts are associated with oxidative stress and DNA damage responses under dysbiotic conditions, while bile acid receptor signaling also affects epithelial renewal and immune tone. This dual role is exactly why metabolomics is needed: it quantifies which bile acids dominate, in which compartment, and in which clinical context, allowing researchers to distinguish potentially pro-tumorigenic bile acid signatures from more homeostatic bile acid pools [5,14].

Polyamines and proliferative wiring

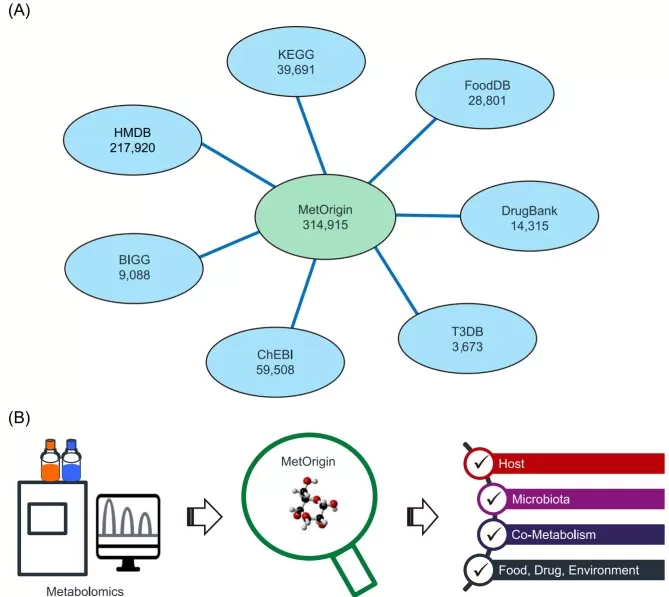

Polyamines sit at the intersection of microbial metabolism and host proliferation programs. Because polyamines can arise from both microbial and host pathways, origin-aware integration approaches improve interpretability and reduce over-attribution. Functionally, polyamines support cell growth and intersect with inflammatory pathways, making them plausible mediators that connect microbial ecosystem shifts to tumor-promoting environments [3,4].

Turning microbial chemistry into a blood test.

A representative integrated analysis combining fecal metagenomics with serum metabolomics reported that a panel of gut microbiome-associated serum metabolites could distinguish CRC/adenoma from controls with strong performance, improving on models built from microbiome features alone [7]. The practical value is twofold: serum metabolites are clinically accessible biomarkers, and the metabolite panel highlights which chemical axes are most linked to disease state, guiding both biomarker translation and mechanistic follow-up.

Chemical Messengers: How Microbial Metabolites Influence Signaling and Physiology

Microbial metabolites influence disease because they engage host biology through concrete mechanisms: receptor binding, epigenetic regulation, barrier maintenance, and immune cell programming. The table below summarizes representative metabolite classes and the best-supported signaling “handles” described.

|

Metabolite class |

Major producers (examples) |

Disease relevance |

Mechanistic handle |

|

Fiber fermenters such as Faecalibacterium and Roseburia |

Obesity/insulin resistance, NAFLD, colonic inflammation, CRC risk modulation [10,11,15] |

Activate host GPCR signaling and modulate gene expression (e.g., via HDAC inhibition), supporting barrier integrity and immune/metabolic regulation [6,11,15]. |

|

|

Indole derivatives (tryptophan metabolites) |

Indole-producing anaerobes (pathway dependent) |

Tumor-associated inflammation and CRC biology; metabolic inflammation [10–12] |

Signal through AhR-related pathways to shape mucosal immunity and epithelial repair, influencing inflammatory tone [12]. |

|

Secondary bile acids (pool shifts; e.g., DCA/LCA) |

Bile acid-transforming pathways (enzyme dependent) |

Digestive diseases, NAFLD, CRC [5,10,14] |

Remodel bile acid receptor signaling (FXR/TGR5) and stress/inflammatory responses, linking gut chemistry to host metabolism and epithelial homeostasis [5,6]. |

|

TMAO and related methylamines |

TMA-producing pathways enriched in some communities |

Cardiometabolic risk and systemic inflammation [1,16] |

Reflect microbial choline/carnitine metabolism and associate with systemic inflammatory and cardiometabolic signaling pathways [16]. |

|

Polyamines |

Multiple taxa plus host co-metabolism |

Inflammation and CRC biology [4,13] |

Support growth and inflammatory programs; origin-aware integration helps distinguish microbial vs host contributions [3]. |

Typical gut microbiota metabolites in modulation of host metabolism

A Practical Research Roadmap: From Discovery to Translation

1) Study design: match evidence level to your question

Cross-sectional cohorts (disease vs. control) are efficient for discovery and biomarker screening, but they mainly provide association. Longitudinal designs—following individuals over time, or sampling before and after therapy—help establish temporal ordering and strengthen causal hypotheses. Multi-stage designs that move from human association to experimental validation are increasingly recommended for microbiome–metabolome research [8,9].

2) Sampling and measurement: pick the compartment that matches the biology

Fecal samples capture the microbial community and luminal metabolites; serum/plasma reflects systemic exposure; urine can provide an additional lens on excretion and broader metabolic effects. For CRC detection, pairing stool and blood has proven particularly informative because it connects local microbial ecosystems to clinically accessible systemic biomarkers [2,7]. Untargeted LC-MS enables broad discovery, while targeted assays (for SCFAs or bile acids) provide quantitative anchors for mechanistic work and clinical translation [2,9].

3) Integration: three tiers that keep analysis interpretable and testable

Tier 1 — Association and pathway mapping. Start with reproducible microbe–metabolite associations and pathway annotation. Tools designed to discriminate metabolite origin help clarify whether a metabolite is likely microbial, host, or co-metabolic [3].

Tier 2 — Prediction and stratification. Use models to identify robust features that generalize across cohorts. Meta-analytic work on microbiome–metabolome associations emphasizes that robustly predicted metabolites—often bile acids, polyamines, and related pathway outputs—can anchor stratification even when taxa differ [4].

Tier 3 — Causal validation. Once candidate pathways are identified, mechanistic pipelines can test production and impact via strain cultivation, ex vivo fermentation, isotope tracing, or transplantation approaches. Standardized metabolomics workflows support this step by making metabolite identification and quantification reliable enough for mechanistic inference [8,9].

Applying MetOrgin for metabolite classifications

Image reproduced from Yu et al., 2022, Imeta, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Conclusion: Metabolomics Helps Us Listen to the “Second Brain”

The gut microbiome speaks in molecules. Metabolomics turns that chemical conversation into measurable signals, allowing us to move beyond “who is there” to “what are they doing, and why does it matter?” In metabolic disease, microbial metabolites convert diet into endocrine and immune signals that shape insulin sensitivity and liver fat pathways. In cancer, the same chemical messengers can influence barrier integrity, oxidative stress, and immune surveillance—offering new angles for diagnosis and therapy [1,13,14].

As integration methods mature, the field is moving from descriptive dysbiosis narratives to mechanism-grounded models with testable targets: metabolite–receptor interactions, pathway bottlenecks such as bile acid remodeling, and serum metabolite panels that translate into clinically accessible biomarkers. The “second brain” holds the code; metabolomics is one of the best ciphers we have to read it without losing the complexity that makes it so powerful [2,6].

References

[1] Liu J, Tan Y, Cheng H, Zhang D, Feng W, Peng C. Functions of Gut Microbiota Metabolites, Current Status and Future Perspectives. Aging Dis. 2022 Jul 11;13(4):1106-1126. doi: 10.14336/AD.2022.0104.

[2] Bauermeister A, Mannochio-Russo H, Costa-Lotufo LV, Jarmusch AK, Dorrestein PC. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics in microbiome investigations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022 Mar;20(3):143-160. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00621-9.

[3] Yu G, Xu C, Zhang D, Ju F, Ni Y. MetOrigin: Discriminating the origins of microbial metabolites for integrative analysis of the gut microbiome and metabolome. Imeta. 2022 Mar 21;1(1):e10. doi: 10.1002/imt2.10. Erratum in: Imeta. 2023 Nov 06;2(4):e149. doi: 10.1002/imt2.149.

[4] Muller E, Algavi YM, Borenstein E. A meta-analysis study of the robustness and universality of gut microbiome-metabolome associations. Microbiome. 2021 Oct 12;9(1):203. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01149-z.

[5] Fogelson KA, Dorrestein PC, Zarrinpar A, Knight R. The Gut Microbial Bile Acid Modulation and Its Relevance to Digestive Health and Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jun;164(7):1069-1085. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.02.022.

[6] Chang PV. Microbial metabolite-receptor interactions in the gut microbiome. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2024 Dec;83:102539. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2024.102539.

[7] Chen F, Dai X, Zhou CC, Li KX, Zhang YJ, Lou XY, Zhu YM, Sun YL, Peng BX, Cui W. Integrated analysis of the faecal metagenome and serum metabolome reveals the role of gut microbiome-associated metabolites in the detection of colorectal cancer and adenoma. Gut. 2022 Jul;71(7):1315-1325. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323476.

[8] Han S, Van Treuren W, Fischer CR, Merrill BD, DeFelice BC, Sanchez JM, Higginbottom SK, Guthrie L, Fall LA, Dodd D, Fischbach MA, Sonnenburg JL. A metabolomics pipeline for the mechanistic interrogation of the gut microbiome. Nature. 2021 Jul;595(7867):415-420. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03707-9.

[9]. Jin WB, Li TT, Huo D, Qu S, Li XV, Arifuzzaman M, Lima SF, Shi HQ, Wang A, Putzel GG, Longman RS, Artis D, Guo CJ. Genetic manipulation of gut microbes enables single-gene interrogation in a complex microbiome. Cell. 2022 Feb 3;185(3):547-562.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.035.

[10] Cai J, Rimal B, Jiang C, Chiang JYL, Patterson AD. Bile acid metabolism and signaling, the microbiota, and metabolic disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2022 Sep;237:108238. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108238.

[11] Williams LM, Cao S. Harnessing and delivering microbial metabolites as therapeutics via advanced pharmaceutical approaches. Pharmacol Ther. 2024 Apr;256:108605. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2024.108605.

[12] Jia D, Kuang Z, Wang L. The role of microbial indole metabolites in tumor. Gut Microbes. 2024 Jan-Dec;16(1):2409209. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2409209.

[13] Gou H, Zeng R, Lau HCH, Yu J. Gut microbial metabolites: Shaping future diagnosis and treatment against gastrointestinal cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2024 Oct;208:107373. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107373.

[14] Xie Y, Liu F. The role of the gut microbiota in tumor, immunity, and immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2024 Jun 5;15:1410928. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1410928.

[15] Vich Vila A, Zhang J, Liu M, Faber KN, Weersma RK. Untargeted faecal metabolomics for the discovery of biomarkers and treatment targets for inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2024 Oct 7;73(11):1909-1920. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-329969.

[16] Li C, Stražar M, Mohamed AMT, Pacheco JA, Walker RL, Lebar T, Zhao S, Lockart J, Dame A, Thurimella K, et al. Gut microbiome and metabolome profiling in Framingham heart study reveals cholesterol-metabolizing bacteria. Cell. 2024 Apr 11;187(8):1834-1852.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.03.014.

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.