Choosing the Best Proteomics Quantification Strategy: A Comprehensive Guide

Proteomics is an indispensable tool in contemporary biological research, providing critical insights into the complexity of the proteome and its alterations under various conditions. Accurately quantifying proteins is essential for understanding disease mechanisms, identifying potential biomarkers, monitoring therapeutic responses, and elucidating cellular processes. However, selecting the appropriate quantification strategy is crucial for obtaining meaningful results, as each method has distinct advantages, limitations, and optimal use cases.

This article explores three major proteomics quantification strategies—label-based quantification, label-free quantification, and targeted quantification—by examining their underlying principles, technologies, strengths, limitations, and applications. Additionally, we offer guidance on how to choose the most appropriate proteomics strategy for your specific research objectives and provide real-world application scenarios that further illustrate the practical use of each method.

1. Label-based Quantification: Achieving Precision Through Labeling

Principle and Core Technologies

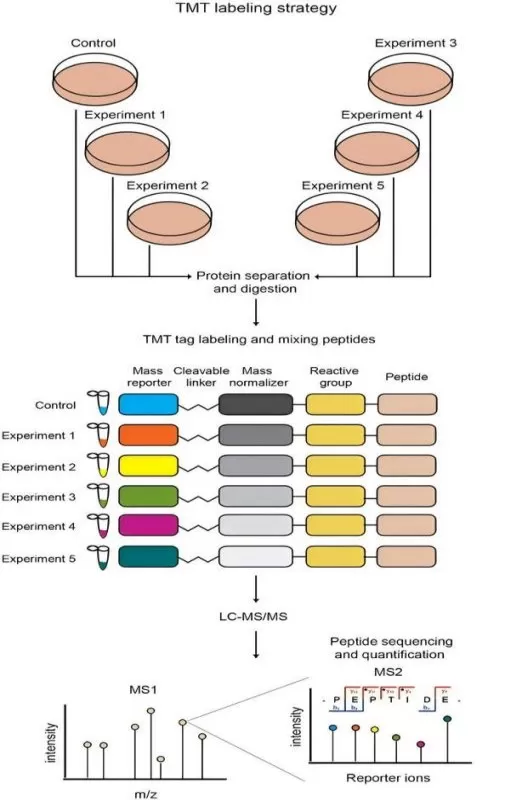

Label-based quantification techniques involve incorporating stable isotope labels or chemical tags into proteins or peptides, enabling the pooling of multiple samples for simultaneous analysis. These labels facilitate precise quantification by distinguishing samples based on mass shifts introduced by the labels. The two primary label-based approaches are Isobaric Chemical Labeling and Metabolic Labeling.

· Isobaric Chemical Labeling (e.g., TMT, iTRAQ): Isobaric labels are chemical tags that share the same nominal mass but differ in the mass of reporter ions released upon fragmentation during mass spectrometry. These labels allow for the multiplexing of up to 16 samples in a single experiment, significantly enhancing throughput [1]. The intensity of the reporter ions correlates directly with protein abundance.

· Metabolic Labeling (e.g., SILAC): Metabolic labeling involves the incorporation of isotopically labeled amino acids into proteins during cell culture. This method enables direct comparison between labeled and unlabeled proteins, making it particularly useful in systems where isotope incorporation is feasible, such as cell cultures.

Both techniques rely on tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) to quantify proteins based on the intensity of reporter ions or isotope-labeled peptides. (Learn more at: Label-based Protein Quantification Technology—iTRAQ, TMT, SILAC)

Comparison of Chemical (TMT) and Metabolic (SILAC) Quantitative Proteomics Strategies.

Image reproduced from Giambruno, R., Mihailovich, M., Bonaldi, T, 2018, Frontiers in molecular biosciences, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

Strengths, Limitations, and Best Use Cases

Strengths

Label-based quantification offers high precision and reproducibility, particularly when comparing multiple experimental conditions. By pooling labeled samples, experimental variability is minimized, ensuring reliable results. This approach is especially beneficial for studies requiring accurate comparisons across multiple experimental groups. Additionally, isobaric chemical tagging facilitates high-throughput analysis, enabling the simultaneous examination of up to 16 samples in a single run.

Limitations

However, label-based quantification is limited by its high cost and constraints in sample multiplexing. The isotopic or chemical reagents needed for labeling can be expensive, and the number of conditions that can be multiplexed is constrained by the availability of these reagents. Co-isolation interference can also occur when peptides with similar ionization efficiencies are co-isolated during the same MS scan, potentially leading to inaccurate quantification. Moreover, these methods require careful optimization to avoid issues such as reduced sensitivity or poor labeling efficiency.

Best Use Cases

Label-based quantification is particularly effective for multi-group comparison studies or time-course experiments that demand high precision. It is commonly applied in clinical studies involving multiple treatment groups or large-scale biomarker discovery efforts, where comparing various experimental conditions is necessary.

2. Label-free Quantification: Flexibility, Scalability, and Cost-effectiveness

Principle and Core Technologies

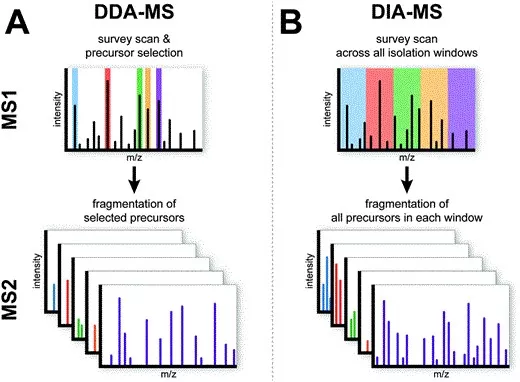

Label-free quantification (LFQ) determines protein abundance without the use of isotopic or chemical labels. Instead, it relies on signal intensities or spectral counts derived from mass spectrometry data. There are two main approaches to LFQ: Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) and Data-independent acquisition (DIA).

· DDA (Data-dependent Acquisition): In DDA, the mass spectrometer selects the most abundant ions for fragmentation based on their intensity. This method is widely used in discovery proteomics, enabling deep proteome profiling and capturing both abundant and low-abundant proteins. However, DDA can suffer from stochastic sampling, where peptides with low ionization efficiencies may be missed, leading to missing data and reduced reproducibility, particularly in complex samples.

· DIA (Data-independent Acquisition): DIA overcomes the limitations of DDA by fragmenting all ions within a predefined m/z window during each cycle. This ensures that no peptide is excluded, improving reproducibility and quantification accuracy. DIA is particularly valuable for large-scale studies, as it reduces the likelihood of missing data, leading to more consistent measurements across runs. While DIA’s sensitivity is somewhat lower than DDA due to the fragmentation of all ions, it provides more reliable and comprehensive data for cohort analyses, ensuring consistency across samples.

The main distinction between DDA and DIA lies in the ion selection process: DDA selectively fragments ions based on intensity, while DIA fragments all ions within a given m/z range, enhancing consistency and minimizing missing values. (Learn more at: DIA Proteomics vs DDA Proteomics: A Comprehensive Comparison)

Comparison of DDA (Data-dependent acquisition) and DIA (Data-independent acquisition) Strategies.

Image reproduced from Krasny and Huang, 2021, Molecular Omics, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 International License (CC BY 3.0).

Strengths, Limitations, and Best Use Cases

Strengths

Label-free quantification is cost-effective, eliminating the need for expensive labeling reagents. This makes LFQ especially advantageous for large-scale studies with numerous samples. Additionally, LFQ is scalable, enabling the analysis of large numbers of samples in parallel. DIA, in particular, offers superior reproducibility compared to DDA, especially in large clinical studies, where consistency is crucial.

Limitations

Despite its cost-effectiveness, LFQ faces challenges such as batch effects and variability between runs, as each sample is analyzed separately. These variations can impact the accuracy of quantification, especially in studies with large sample sizes. Missing values also remain a challenge, particularly in DDA-based LFQ, where peptides may not be detected in all runs.

Best Use Cases

LFQ is ideal for large-scale cohort studies, clinical proteomics, and biomarker discovery where cost efficiency and throughput are priorities [2]. It is particularly beneficial when analyzing biological samples from diverse biological contexts (e.g., plasma, tissues, extracellular vesicles) since it does not require specialized sample preparation beyond standard proteomics workflows.

3. Targeted Quantification: High Sensitivity for Specific Proteins and Peptides

Principle and Core Technologies

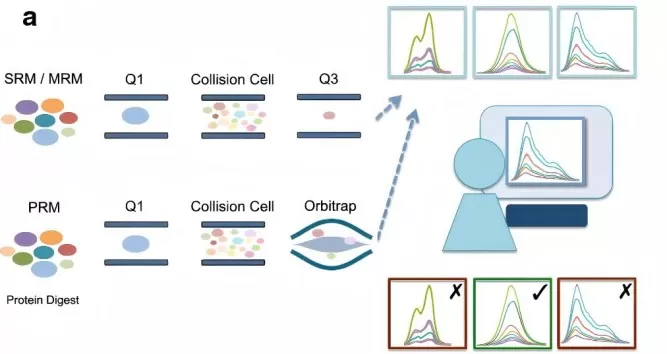

Targeted proteomics focuses on quantifying predefined proteins or peptides with high sensitivity and specificity. Rather than profiling the entire proteome, targeted approaches focus only on specific analytes, providing highly accurate measurements of low-abundance proteins. The two primary targeted methods are:

· SRM/MRM (Selected/Multiple Reaction Monitoring): SRM (or MRM) uses a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer to scan specific transitions of precursor and fragment ions. This method measures one transition per peptide at a time, offering high sensitivity and reproducibility, even for low-abundance proteins. SRM is ideal for biomarker validation and large-scale proteomics but may struggle with complex samples due to its limited ability to resolve co-eluting peptides.

· PRM (Parallel Reaction Monitoring): PRM, similar to SRM, utilizes high-resolution mass spectrometry to monitor multiple transitions from a single precursor ion in parallel. This increases selectivity and accuracy, particularly in complex samples, by distinguishing co-eluting peptides. PRM’s parallel analysis offers higher sensitivity and quantification accuracy compared to SRM, making it better suited for biomarker validation and large peptide panels.

The key difference between SRM/MRM and PRM is that SRM/MRM uses a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer to monitor one transition at a time, while PRM employs high-resolution instruments to monitor multiple transitions, offering superior sensitivity and accuracy in complex proteomic studies. (Learn more at: PRM vs MRM: A Comparative Guide to Targeted Quantification in Mass Spectrometry)

Comparison of SRM and PRM Techniques for Targeted Quantitative Proteomics.

Image reproduced from Toghi Eshghi, S., Auger, P., Mathews, W. R., 2018, Clinical Proteomics, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

Strengths, Limitations, and Best Use Cases

Strengths

Targeted quantification is the most sensitive method for detecting low-abundance proteins. By focusing on specific peptides or proteins, these techniques ensure accurate and reproducible quantification, even in complex biological samples. Additionally, absolute quantification is achievable through the use of isotope-labeled internal standards.

Limitations

The main limitation of targeted quantification is its narrow scope. Unlike label-based or label-free approaches, which profile the entire proteome, targeted methods are limited to predefined peptides or proteins. This makes targeted quantification unsuitable for discovery proteomics, where the identification of novel proteins is required. Additionally, the development of targeted assays can be time-consuming and resource-intensive.

Best Use Cases

Targeted quantification is particularly effective for biomarker validation, where the goal is to confirm the abundance of specific proteins or peptides identified in discovery proteomics. It is also ideal for monitoring low-abundance proteins in clinical applications or for verifying candidate biomarkers in large cohorts. Targeted methods are crucial when quantitative accuracy and reliability are necessary, particularly in highly regulated environments like clinical diagnostics.

4. How to Choose the Right Proteomics Quantification Strategy

Selecting the most appropriate proteomics quantification strategy depends on several key factors, including sample size, the type of analysis (discovery vs. validation), and the need for relative or absolute quantification. Below is a guide to help determine the best strategy for your research.

Sample Size Considerations

For small to moderate sample sizes (e.g., tens to a few hundred samples), label-based methods like TMT or SILAC are ideal. These methods provide high-throughput analysis and enable accurate multi-group comparisons with minimal batch-to-batch variability. The ability to pool labeled samples reduces experimental error and enhances reproducibility, making label-based methods well-suited for smaller experiments or time-course studies. However, as the number of samples increases, the cost of labeling reagents can become prohibitive.

In large-scale studies (e.g., hundreds of samples), label-free quantification methods such as DDA or DIA are more scalable and cost-effective. These techniques allow for the analysis of a large number of samples without the need for labeling reagents. While label-free methods are easier to implement for large cohorts, it is essential to carefully address data normalization and batch effects to maintain accuracy across experiments.

Discovery vs. Validation

For discovery-based studies, where the objective is to identify novel proteins, pathways, or biomarkers, both label-free and label-based methods are suitable. These approaches allow for comprehensive proteome profiling and the detection of new proteins or biomarker candidates. Label-free methods are particularly beneficial when flexibility and scalability are needed, as they can handle large sample sets without the complexities associated with labels.

If your focus is on validation—such as confirming previously identified biomarkers or quantifying specific proteins—targeted quantification methods like SRM or PRM are the best options [3]. These techniques provide high sensitivity and quantification precision, enabling reliable measurement of target proteins, even at low abundance. Targeted methods are essential for biomarker confirmation and targeted validation in clinical or high-accuracy proteomics studies.

Relative vs. Absolute Quantification

All three strategies—label-based, label-free, and targeted quantification—can be used for relative quantification, which involves comparing protein abundances across conditions or time points. These methods provide insights into how proteins vary in response to different experimental variables.

However, if absolute quantification is required, targeted methods are the preferred choice. Techniques like SRM and PRM, which utilize stable isotope-labeled internal standards, allow for precise, absolute measurements of protein concentrations. This is especially important in clinical studies, where exact protein levels are necessary for diagnostic purposes or therapeutic monitoring.

In summary, the optimal strategy for your study will depend on your sample size, whether the focus is on discovery or validation, and the need for relative or absolute quantification. By aligning your objectives with the appropriate method, you can ensure the generation of reliable and meaningful proteomics data.

Comparison of Proteomics Quantification Methods

|

Feature |

Label-based (TMT/iTRAQ, SILAC) |

Label-free (DDA/DIA) |

Targeted (SRM/MRM, PRM) |

|

Sample Size |

Best for moderate sizes (tens to a few hundred) |

Ideal for large-scale studies (hundreds) |

Suitable for moderate to large sets |

|

Discovery vs. Validation |

Primarily for discovery (protein identification) |

Primarily for discovery and profiling, less suited for validation |

Best for validation (biomarker confirmation) |

|

Relative vs. Absolute Quantification |

Relative quantification |

Primarily relative, can do absolute with standards |

Best for absolute quantification |

|

Throughput |

Limited throughput due to multiplexing |

High throughput, ideal for large datasets |

Medium-to-high throughput |

|

Reproducibility |

High within multiplexed samples, variable across batches |

High, especially with DIA ensuring consistency across runs |

Very high for targeted peptides |

|

Cost |

Higher due to labeling reagents |

Lower, no labeling needed |

Moderate, depends on assay design |

5. Typical Application Scenarios: From Multi-group Screening to Clinical Cohorts

Scenario 1: TMT for Multi-group Differential Screening

For studies involving the comparison of multiple experimental groups (e.g., treatment vs. control), TMT (Tandem Mass Tag) provides a high-throughput, multiplexed solution. TMT allows for the simultaneous analysis of multiple conditions in a single experiment, making it an excellent choice for clinical trials or time-course experiments where precision and efficiency are crucial. By labeling and pooling samples before mass spectrometry analysis, TMT minimizes experimental variation and enhances comparability across conditions. This is particularly advantageous for identifying protein expression differences between multiple groups, especially when many conditions need to be compared efficiently.

Scenario 2: DIA for Large-Scale Clinical Proteomics

In large cohort studies, particularly in clinical settings where many patient samples must be analyzed, DIA (Data-independent Acquisition) offers robust quantification and excellent reproducibility. DIA systematically fragments all ions within predefined m/z windows, ensuring comprehensive proteome analysis with reduced missing data. This systematic approach enhances result consistency across multiple runs, making it ideal for large-scale clinical studies or population-wide proteomics research. The ability to provide consistent and reproducible data is vital for studying complex biological processes across many samples while ensuring high accuracy in quantification.

Scenario 3: PRM for Biomarker Validation

For biomarker validation, where previously identified biomarkers need to be confirmed across multiple samples, PRM (Parallel Reaction Monitoring) is the preferred technique. PRM uses high-resolution mass spectrometry to monitor multiple transitions from a single precursor ion in parallel, improving selectivity and quantification accuracy. This method is particularly valuable for quantifying low-abundance biomarkers in complex biological samples, such as plasma or tissue extracts. PRM’s high sensitivity allows for the precise quantification of proteins, even at very low concentrations, making it an indispensable tool for confirming biomarkers identified in earlier discovery phases or verifying protein signatures in clinical applications.

These application scenarios illustrate how each proteomics quantification method is optimized for different experimental needs, from high-throughput differential screening and large-scale cohort profiling to biomarker validation. Each technique offers unique advantages depending on the research focus, providing accurate and reproducible results across diverse proteomics studies.

References:

1. Thompson, A., Schäfer, J., Kuhn, K., Kienle, S., Schwarz, J., Schmidt, G., Neumann, T., Johnstone, R., Mohammed, A. K., & Hamon, C. (2003). Tandem mass tags: a novel quantification strategy for comparative analysis of complex protein mixtures by MS/MS. Analytical chemistry, 75(8), 1895–1904. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac0262560

2. Gillet, L. C., Navarro, P., Tate, S., Röst, H., Selevsek, N., Reiter, L., Bonner, R., & Aebersold, R. (2012). Targeted data extraction of the MS/MS spectra generated by data-independent acquisition: a new concept for consistent and accurate proteome analysis. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP, 11(6), O111.016717. https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.O111.016717

3. Picotti, P., & Aebersold, R. (2012). Selected reaction monitoring-based proteomics: workflows, potential, pitfalls and future directions. Nature methods, 9(6), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2015

4. Giambruno, R., Mihailovich, M., & Bonaldi, T. (2018). Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics to Unveil the Non-coding RNA World. Frontiers in molecular biosciences, 5, 90. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2018.00090

5. Krasny, L., & Huang, P. H. (2021). Data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) for proteomic applications in oncology. Molecular omics, 17(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0mo00072h

6. Toghi Eshghi, S., Auger, P., & Mathews, W. R. (2018). Quality assessment and interference detection in targeted mass spectrometry data using machine learning. Clinical proteomics, 15, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-018-9209-x

Read more:

- Mass Spectrometry Acquisition Mode Showdown: DDA vs. DIA vs. MRM vs. PRM

- Proteomics Platform Showdown: MS-DIA vs. Olink vs. SomaScan

- Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Proteomics: Unraveling the Secrets of Protein Analysis

- Comprehensive Guide to Basic Bioinformatics Analysis in Proteomics

- Strategies for Selecting Key Interacting Proteins in IP-MS Studies

- Peptide and Protein De Novo Sequencing by Mass Spectrometry

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.