Comprehensive Overview of Single-Cell Proteomics: Methods, Technologies, and Workflow

Single-cell proteomics has transformed our understanding of cellular biology by allowing us to study proteins at the resolution of individual cells. This rapidly advancing field is reshaping how we investigate cellular heterogeneity, offering critical insights into cellular function, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic responses. In this blog, we provide a comprehensive overview of single-cell proteomics, examining its key methods, technologies, workflows, as well as the challenges and opportunities it presents.

What Is Single-Cell Proteomics and How Did It Emerge?

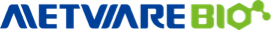

Proteomics is the large-scale characterization of proteins and their functions within biological systems. Single-cell proteomics is a specialized branch of proteomics that focuses on analyzing the protein content and functional activity within individual cells. Traditional bulk proteomics analyzes pooled populations of thousands to millions of cells to obtain an averaged protein profile [1]. While bulk analysis has greatly advanced biological research, it inherently masks cell-to-cell heterogeneity. In many contexts, this hidden variation is biologically significant—for example, rare tumor subpopulations (sometimes <0.1%) may drive drug resistance, yet their distinct protein signatures are lost within bulk averages. Single-cell proteomics aims to overcome this limitation by profiling proteins in individual cells, revealing differences that bulk analysis would obscure.

Fig. 1 Bulk vs. single-cell analysis. Bulk measurements average signals from many cells, obscuring distinct cell subpopulations. Single-cell proteomics isolates individual cells (via targeted or non-targeted approaches) and produces profiles (e.g. heat maps) for each cell, allowing identification of heterogeneous subpopulations[2]

The motivation for single-cell proteomics parallels the revolution brought by single-cell genomics and transcriptomics. Single-cell DNA and RNA sequencing have revealed extensive molecular heterogeneity across tissues [1]. However, understanding true cellular function requires direct measurement of proteins—the molecules that execute biological processes. Protein abundance, activity, and post-translational modifications (PTMs) often diverge from mRNA levels, making transcriptomics an incomplete proxy for cellular phenotype [1]. By resolving proteins at single-cell resolution, researchers can more accurately characterize signaling pathways, enzyme activities, and functional cell states.

Achieving this depth of analysis at the single-cell scale is technologically challenging. Unlike nucleic acids, proteins cannot be amplified, and a single mammalian cell contains only picograms of total protein. Individual protein copy numbers span up to seven orders of magnitude, complicating the detection of low-abundance targets—sometimes referred to as the dark proteome. Despite these barriers, rapid advances in ultrasensitive sample preparation, nano-flow liquid chromatography, and high-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) have enabled the emergence of robust single-cell proteomics workflows. State-of-the-art methods now routinely identify over 4,000 proteins per individual cell using advanced MS technologies [3, 4].

Why Single-Cell Proteomics Matters: Core Values and Impact

Single-cell proteomics emerges from the recognition that biological systems are inherently heterogeneous. Even genetically identical cells can exhibit significant differences in protein expression due to stochastic gene expression, microenvironmental factors, or variations in cell cycle and differentiation states. In both health and disease, rare cell types or outlier cells often have disproportionate effects. For example, in cancer, a small subset of cells may harbor a unique protein expression profile that drives metastasis or confers drug resistance. In the immune system, rare antigen-specific lymphocytes or activated cells are crucial for initiating and regulating responses. Bulk proteomic analysis, by averaging these signals, would obscure such critical variations, whereas single-cell proteomics can precisely identify and measure them.

Another key reason is the disconnect often observed between mRNA and protein levels. mRNA transcripts are sometimes used as proxies for protein, but mRNA abundance does not always predict protein abundance in the same cell[1]. It also detects PTMs (like phosphorylation, acetylation, etc.) that modulate protein function but are invisible to transcriptomic assays. This is crucial for understanding signaling networks and functional state – for instance, whether a cell’s signaling protein is in an active (phosphorylated) form or not. Single-cell proteomics therefore complements single-cell genomics and transcriptomics.

Another key factor driving the need for single-cell proteomics is the frequent disconnect between mRNA and protein levels. While mRNA is often used as a proxy for protein expression, mRNA abundance does not always correlate with protein levels in the same cell [1]. Moreover, mRNA-based approaches cannot capture post-translational modifications (PTMs)—such as phosphorylation or acetylation—that are essential for regulating protein function. These modifications are critical for understanding signaling networks and the functional state of a cell. For instance, whether a signaling protein is in an active (phosphorylated) form or not is crucial for its role in cellular processes, yet this cannot be inferred from transcriptomic data alone.

Single-cell proteomics thus complements single-cell genomics and transcriptomics, together forming a comprehensive multi-omics toolkit. This integration provides a holistic view of cellular identity and functional states. While single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) can define cell types and transcriptional states across thousands of cells, revealing gene expression patterns and subpopulations, single-cell proteomics adds another critical layer. It bridges the gap between gene expression and protein function by showing how these expression patterns translate into protein networks and cellular phenotypes. For example, scRNA-seq can identify a new subpopulation of cells in a tissue, and targeted single-cell proteomic assays can then characterize the proteins (such as surface markers and signaling proteins) that define and regulate this subpopulation. This dual approach is particularly valuable in clinical research and diagnostics, where understanding how small clusters of cells differ at the protein level can illuminate disease mechanisms and inform treatment responses.

Finally, single-cell proteomics is essential for studying cell–cell interactions and spatial biology. Cells in tissues do not exist in isolation but communicate via secreted proteins and direct physical contacts. To decode these complex interactions, both single-cell resolution and spatial information are required. Emerging spatial proteomics techniques aim to map proteins within intact tissue sections at single-cell or even sub-cellular resolution. This enables researchers to study how the microenvironment or the proximity of different cell types influences protein expression—for example, how tumor cells differ from immune cells at the invasive edge of a tumor versus its core.

In summary, single-cell proteomics offers a powerful tool to:

- Uncover cellular heterogeneity in protein expression that is hidden in bulk analyses.

- Directly measure functional molecules—proteins and their post-translational modifications—that drive cellular phenotypes, complementing genomic data.

- Identify rare cells or subpopulations (e.g., resistant cancer cells, specific immune cell clones) that are critical in both research and clinical contexts.

- Provide spatial context to proteomic data, linking cell location with protein function in tissues.

How to Perform Single-Cell Proteomics: Key Methods and Workflows

At the single-cell level, two primary approaches for proteome analysis have emerged: antibody-based methods [5] and mass spectrometry-based methods [6]. More recently, hybrid techniques, imaging-based methods, and emerging single-molecule protein sequencing approaches have broadened the available toolkit. Each method differs in how it detects proteins and in the trade-offs between proteome coverage, sensitivity, throughput, and spatial resolution. Below, we discuss each approach, its principles, and provide a comparative analysis of their key characteristics.

Antibody-Based Single-Cell proteomics Methods (Targeted Proteomics)

Antibody-based single-cell proteomics uses affinity reagents (such as antibodies or similar binders) to specifically recognize target proteins. These methods are inherently targeted, meaning the proteins (antigens) to be measured must be predetermined, and corresponding antibodies must be available. The readout typically involves light or mass signals attached to each antibody, indicating the presence and quantity of the protein in each cell.

Technological Principles of Antibody-Based Single-Cell Proteomics Methods

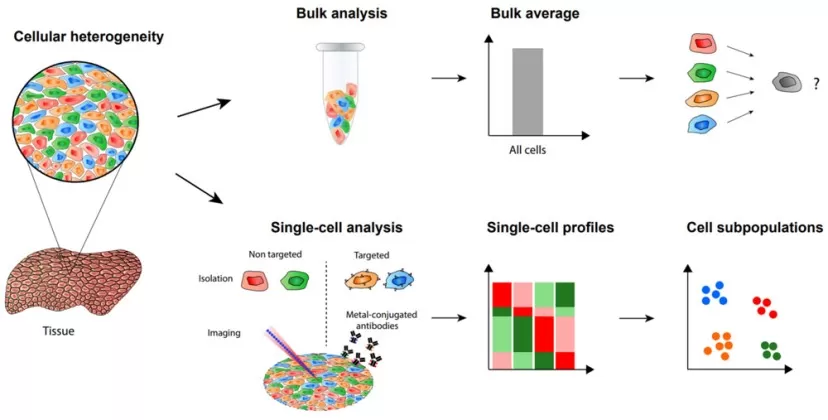

- Mass Cytometry (CyTOF) – An advanced form of cytometry that increases multiplexing by using heavy metal isotopes as antibody labels instead of fluorophores[7,8]. Mass cytometry (CyTOF) uses metal-tagged antibodies and time-of-flight mass spectrometry to quantify ~40 proteins per cell with minimal overlap, enabling high-throughput, multiplexed single-cell profiling of surface/intracellular targets, but is constrained by the finite set of metal labels and validated antibodies.

- DNA-Barcoded Antibody Assays (CITE-seq and others) – DNA-barcoded antibody assays like CITE-seq label antibodies with unique DNA oligos; after cell binding, the tags are sequenced to quantify proteins alongside scRNA-seq, enabling ~10–100 protein measurements per cell. They provide targeted, multimodal single-cell data but are limited by antibody specificity, cross-reactivity, and panel validation effort.

- Highly Multiplexed Imaging (Imaging Mass Cytometry, CODEX, MIBI, etc.) – These methods extend antibody-based proteomics into the spatial domain, allowing protein mapping in tissues at single-cell resolution. Antibody-driven spatial proteomics—Imaging Mass Cytometry (laser ablation of metal-tagged antibodies plus CyTOF, ~40-plex), Multiplexed Ion Beam Imaging (ion beam sputtering of metal labels, ~100-plex, sub-cellular resolution), and CODEX (iterative cycles of DNA-barcoded antibodies with fluorescence, 10–60-plex)—map dozens of proteins across thousands of single cells within native tissue architecture, yet remain constrained by antibody specificity, predefined target panels, and limited imaging area/throughput.

Fig. 2 Schematic representation of a workflow of high-throughput single-cell proteomics analysis using CyTOF[2]

Workflow of Antibody-Based Single-Cell Proteomics Methods

In summary, antibody-based single-cell proteomics works by labeling each cell’s proteins of interest with specific probes, then detecting those probes one cell at a time. Whether the readout is fluorescence, metal isotopes, or DNA sequencing (fig. 2), the core workflow involves:

1) Cell Labeling – Isolated cells or tissue sections are incubated with a cocktail of antibodies against the target proteins.

2) Single-Cell Resolution Detection – The labeled cells are then processed through flow cytometers, CyTOF instruments, sequencers (for DNA-barcoded tags), or imaging systems to detect the proteins.

3) Data Readout – A quantitative signal per protein is obtained from each individual cell. The result is a matrix of protein abundances for each single cell, but only for the proteins targeted in the initial panel.

Advantages and Limitations of Antibody-Based Single-Cell Proteomics Methods

A major advantage is that these methods can be highly high-throughput (flow/CyTOF can analyze thousands to millions of cells in an experiment) and often cheaper/faster per cell than mass spectrometry. The major drawback is they are not comprehensive – you might measure 20, 40, or 100 proteins per cell, but not discover new proteins beyond the panel. They are best suited for hypothesis-driven studies (e.g., checking known markers, clinical phenotyping panels) or when you need to profile very large numbers of cells. Antibody-based methods also require high-quality antibodies for every target, and issues like non-specific binding or differing antibody affinities can complicate quantitative interpretation.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Single-Cell Proteomics Methods (Unbiased Proteomics)

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based single-cell proteomics takes an untargeted approach, distinguishing it from antibody-based methods. Rather than pre-selecting proteins for measurement, MS-based techniques aim to identify and quantify as many proteins as possible from a single cell's protein extract. This approach mirrors traditional shotgun proteomics used for larger samples, but scaled down to the nanogram or sub-nanogram protein levels found in a single cell.

Technological Principles of MS-Based Single-Cell Proteomics Methods

- SCoPE-MS (Single-Cell ProtEomics by Mass Spectrometry): A foundational implementation, SCoPE-MS[9], labels each single-cell lysate with a discrete TMT channel and supplements the multiplex with a 100-cell “carrier” aliquot. The carrier elevates ion currents to ensure reliable peptide identification; its constant contribution is subsequently deconvoluted, leaving the single-cell reporters to encode relative abundance. This strategy routinely quantifies ~1,000 proteins per cell and resolves distinct cell-type proteomic signatures. SCoPE-MS overcame two bottlenecks: (i) near-lossless delivery of single-cell protein cargo via manual picking and nanolitre lysis, and (ii) confident peptide ID/quantification by carrier-augmented TMT multiplexing. Its successor, SCoPE2[10], automated and miniaturized sample prep (mPOP: freeze–heat lysis in sub-μL volumes), raising throughput to ~200 cells day⁻¹ on conventional instruments and covering ~3,000 proteins in 1,500 immune cells—an order-of-magnitude advance over SCoPE-MS.

- NanoPOTS (Nanodroplet Processing in One Pot for Trace Samples): Beyond SCoPE, microfluidic innovations such as NanoPOTS[11] (Nanodroplet Processing in One Pot for Trace Samples) shrink reaction volumes to nanolitres, confining lysis and digestion to a single droplet within a micro-well chip and thereby eliminating transfer losses and surface adsorption. Coupled to ultrasensitive LC-MS, NanoPOTS routinely quantifies 1,500–3,000 proteins from 10–100 cells, and its nested successor (N²) is being engineered to deliver true single-cell sensitivity while integrating on-chip multiplexed labelling[12].

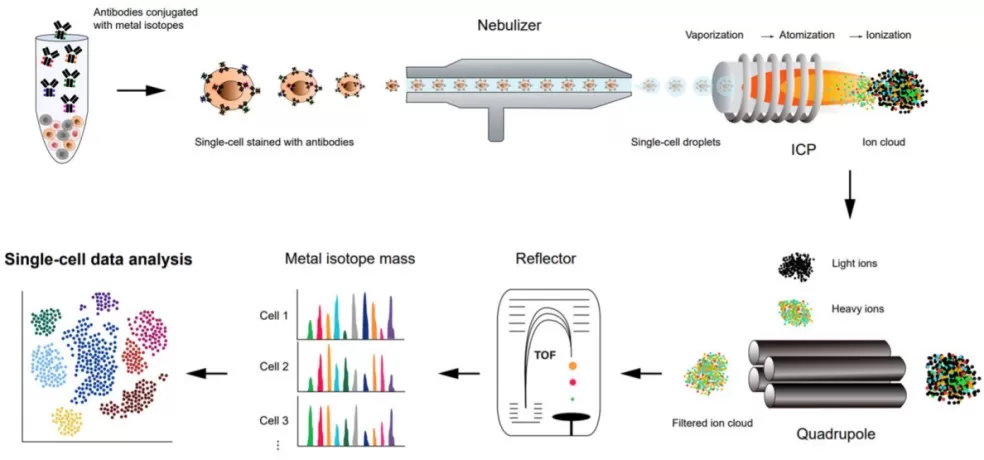

Fig. 3 MS-based single cell proteomics workflow[6]

Workflow of MS-Based Single-Cell Proteomics Methods

The general workflow for single-cell MS proteomics is (Fig. 3):

1) Single-cell isolation: Individual cells are isolated from a suspension (commonly by FACS sorting or micro-manipulation) and deposited into tiny containers (like a well of a microwell plate or a nano-vial on a microchip). Cells can also be isolated by micromanipulation or laser capture microdissection from tissues. Each cell is kept separate for the rest of the process.

2) Cell lysis and protein digestion: Cells are lysed using specialized protocols to minimize protein loss, employing small volumes and avoiding adsorptive surfaces. Proteins are digested into peptides with enzymes (e.g., trypsin) for easier separation and identification in mass spectrometry. All steps are meticulously executed in one container to prevent material loss.

3) Peptide separation and MS analysis: Peptides from a single cell are analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS). They are typically first separated using liquid chromatography (nanoLC) based on chemical properties. In the MS, peptides are ionized, their mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios measured, and fragmented to generate sequence data for identification. This identifies the originating proteins. Due to minute peptide quantities, single-cell MS requires instruments with ultra-high sensitivity and optimized settings. Recent studies achieve identification of ~4000 or more proteins per cell on average by using Orbitrap Astral or timsTOF instrument[3, 4].

4) Data acquisition strategies: Mass spectrometry data acquisition uses two main modes: data-dependent (DDA) and data-independent (DIA). In DDA (used in early single-cell proteomics), the instrument fragments the top N peptide signals per scan, potentially missing lower-abundance peptides due to stochastic sampling. This causes "missing values" when peptides are inconsistently detected across cells. DIA overcomes this by fragmenting all peptides within predefined m/z windows, ensuring consistent detection. For example, diaPASEF combining DIA with parallel accumulation-serial fragmentation on timsTOF instruments—quantified >2,000 proteins per single cell with high completeness (low missing data). This marks a major improvement in single-cell proteomics data quality.

5) Quantification: Identified peptides act as proxies for parent proteins. Quantification is either label-free—single-cell runs yield ion-current intensities—or multiplexed via isobaric tags. Label-free single-cell measurements suffer from low abundance and high variability. TMT multiplexing overcomes this: each cell is derivatised with a mass-balanced tag, samples are pooled, and after co-isolation and co-fragmentation, reporter ions encode cellular origin. Pooling accumulates signal from identical peptides across cells, boosting sensitivity and throughput (10–16-plex) while eliminating run-to-run variance.

Advantages and Limitations of MS-Based Single-Cell Proteomics Methods

MS-based single-cell proteomics remains constrained by low throughput, high cost, and limited sensitivity. Analyzing a few hundred cells demands weeks of instrument time and expert labor, in contrast to sequencing-based assays that profile thousands of cells in parallel. Individual runs require ~1–2 h per cell, although multiplexing and methods such as PlexDIA[13, 14] are accelerating acquisition. Instrumentation is expensive and restricted to specialized labs, and data interpretation requires sophisticated algorithms to extract signals from low-input, noisy spectra. Critically, many low-abundance regulators (e.g., transcription factors) evade detection. Advances in sample preparation and instrumentation continue to push these boundaries.

Emerging Single-Molecule Protein Sequencing

An exciting frontier in proteomics is the development of single-molecule protein sequencing technologies. These methods aim to identify proteins one molecule at a time, without needing large populations or even amplification. Single-molecule techniques could theoretically detect every protein species in one cell, including 1–10 copy regulators undetectable by MS or antibodies.

Several approaches are being explored. Nanopore strategies[15, 16]—adapting DNA-sensing pores to peptides—aim to decode primary structure from ionic-current modulations, but the 20-letter amino-acid alphabet plus post-translational heterogeneity exceeds the chemical resolution of current pores. Incremental signal fingerprints for selected residues or modifications have been reported, yet single-amino-acid discrimination remains unresolved; materials and sensing chemistry are under active refinement. Stepwise single-molecule Edman degradation[17] and cyclic fluoroselective labeling[18] are being re-engineered for single-residue resolution, coupling sequential N-terminal cleavage or motif-specific tagging to total-internal-reflection microscopy. Parallel implementations confine individual proteins to high-density nanoarrays and subject each molecule to iterative, probe-encoded chemistries (affinity reagents, reactive motifs) that accumulate a diagnostic fingerprint decoded in situ. Nautilus Biotechnology and academic consortia are scaling this concept to >10⁸ single-molecule features per run, aiming for proteome-wide, single-copy sensitivity; however, these platforms remain pre-commercial with undisclosed error rates and limited public validation.

Which Single-Cell Proteomics Method Is Best? A Comprehensive Comparison

Each of the approaches above has distinct advantages and limitations. Below is a summary comparing them:

|

Technology |

Proteins/cell |

Throughput |

Targeted |

Spatial |

Key strengths |

Key limitations |

|

Antibody-based (flow/CyTOF/CITE-seq) |

10–100 |

10⁴–10⁶ cells/run |

Yes |

Optional (imaging variants) |

High throughput; easy coupling to sorting/sequencing; quantitative phenotyping |

Limited to known epitopes; antibody availability/cross-reactivity; multiplex ≤100 |

|

MS-based (LC-MS/MS with isobaric tags) |

1,000–3,000+ |

10²–10³ cells/study |

No |

No |

Untargeted; isoform/PTM detection; discovery power |

Low throughput; complex workflow; missing low-copy proteins; expensive |

|

Imaging spatial proteomics (CyCIF/IMC/MIBI/MALDI) |

10–50 (antibody) or 100s features (MALDI) |

10²–10³ ROIs/day |

Yes/No |

Sub-cellular |

Protein localization in situ; tissue architecture |

Limited multiplex or ID confidence; slow whole-slide acquisition; advanced image analysis |

|

Single-molecule sequencing-style arrays |

Theoretical complete proteome |

<10² cells/run (demo stage) |

No |

No |

Single-molecule sensitivity; digital counting; ultra-rare detection |

Experimental; high error; low throughput; restricted to tagged/accessible proteins |

The Future of Single-Cell Proteomics in Research and Medicine

In conclusion, single-cell proteomics represents the next frontier in understanding biology at the most fundamental level of the cell. It answers questions that could not even be asked before – about how individual cells differ in protein makeup and how those differences drive phenotypic outcomes. The field is rapidly evolving, with multiple complementary technologies pushing the boundaries of detection and throughput. Already, researchers can profile thousands of proteins in a single cell by mass spectrometry, or analyze the distributions of tens of proteins across the cells of a tissue by imaging, among other feats. These technologies are illuminating cellular heterogeneity in new ways, from identifying new cell states in tumors to revealing how protein signaling varies in immune cell subsets.

There are certainly challenges to overcome, as we detailed – from technical hurdles like sensitivity and data completeness to practical issues of standardization. But the trajectory of progress suggests these will be met with ingenuity and collaboration. As an editorial in Nature Methods noted, “these are exciting times for single-cell proteomics, with tremendous potential to unlock new biological insight”. By continuing to improve the methods and integrating them with other single-cell analyses, scientists and clinicians will be able to ask and answer questions about cells that were previously out of reach. Single-cell proteomics is transforming our view of cellular biology from a homogenized ensemble to a rich mosaic, where each cell’s protein landscape can be appreciated in full detail – and that is key to deciphering the complexities of life, health, and disease in the coming years.

References

1. Single-cell proteomics: challenges and prospects. Nat Methods, 2023. 20(3): p. 317-318.

2. Lee, S., et al., Advances in Mass Spectrometry-Based Single Cell Analysis. Biology (Basel), 2023. 12(3).

3. Ye, Z., et al., Enhanced sensitivity and scalability with a Chip-Tip workflow enables deep single-cell proteomics. Nat Methods, 2025. 22(3): p. 499-509.

4. Ctortecka, C., et al., Automated single-cell proteomics providing sufficient proteome depth to study complex biology beyond cell type classifications. Nat Commun, 2024. 15(1): p. 5707.

5. Huang, L., et al., Current Advances in Highly Multiplexed Antibody-Based Single-Cell Proteomic Measurements. Chem Asian J, 2017. 12(14): p. 1680-1691.

6. Beck, L. and T. Geiger, MS-based technologies for untargeted single-cell proteomics. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2022. 76: p. 102736.

7. Tracey, L.J., Y. An, and M.J. Justice, CyTOF: An Emerging Technology for Single-Cell Proteomics in the Mouse. Curr Protoc, 2021. 1(4): p. e118.

8. Bandura, D.R., et al., Mass cytometry: technique for real time single cell multitarget immunoassay based on inductively coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal Chem, 2009. 81(16): p. 6813-22.

9. Budnik, B., et al., SCoPE-MS: mass spectrometry of single mammalian cells quantifies proteome heterogeneity during cell differentiation. Genome Biol, 2018. 19(1): p. 161.

10. Petelski, A.A., et al., Multiplexed single-cell proteomics using SCoPE2. Nat Protoc, 2021. 16(12): p. 5398-5425.

11. Zhu, Y., et al., Nanodroplet processing platform for deep and quantitative proteome profiling of 10-100 mammalian cells. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 882.

12. Woo, J., et al., High-throughput and high-efficiency sample preparation for single-cell proteomics using a nested nanowell chip. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 6246.

13. Derks, J. and N. Slavov, Strategies for Increasing the Depth and Throughput of Protein Analysis by plexDIA. J Proteome Res, 2023. 22(3): p. 697-705.

14. Thielert, M., et al., Robust dimethyl-based multiplex-DIA doubles single-cell proteome depth via a reference channel. Mol Syst Biol, 2023. 19(9): p. e11503.

15. Li, M.Y., et al., Nanopore approaches for single-molecule temporal omics: promises and challenges. Nat Methods, 2025. 22(2): p. 241-253.

16. Afshar Bakshloo, M., et al., Nanopore-Based Protein Identification. J Am Chem Soc, 2022. 144(6): p. 2716-2725.

17. Swaminathan, J., A.A. Boulgakov, and E.M. Marcotte, A theoretical justification for single molecule peptide sequencing. PLoS Comput Biol, 2015. 11(2): p. e1004080.

18. Swaminathan, J., et al., Highly parallel single-molecule identification of proteins in zeptomole-scale mixtures. Nat Biotechnol, 2018.

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.