Urine Metabolomics: Urinary Metabolites and Testing Best Practices

Urine metabolomics is an increasingly powerful tool for extracting biochemical information from a non-invasive biofluid. The urine metabolome – the complete set of metabolites in urine – offers a unique window into both systemic metabolism and kidney-specific processes. In this post, we’ll explore why urine is a valuable sample for metabolomics, how to design and normalize urine metabolite studies, and what insights can be gained across health, nutrition, exposure, and stress domains. Urinary metabolites can reveal diet and microbiome influences, kidney function, toxic exposures, and hormone fluctuations. Read on for best practices (from first-morning urine collections to creatinine normalization), and learn how cutting-edge LC–MS urine metabolomics and NMR techniques translate raw data into actionable metabolic insights.

- Why Urine?Advantages and Limitations for Metabolomics

- Urine Metabolomics Study Design &Sample Collection Best Practices

- Normalization Strategies That Matter

- Analytical Platforms &Coverage in Urine Metabolomics

- Quality Control &Data Integrity in Urine Metabolomics

- Kidney and Urological Applications of Urine Metabolomics

- Nutritional and Microbiome-Derived Signatures in Urine

- Toxicological and Occupational Exposure Biomarkers in Urine Metabolomics

- Using Urinary Metabolites for Stress and Endocrine Monitoring

- Get Started with Urine Metabolomics and Urine Metabolite Testing

Why Urine for Metabolomics? Advantages and Limitations

Urine vs Plasma/Serum vs Feces

Compared with plasma or serum, urine metabolomics offers a non-invasive, stress-free sampling option that reflects cumulative metabolic activity rather than a single time point. The urine metabolome captures excreted end-products, diet-derived molecules, and microbiome metabolites that may not appear in blood. While plasma metabolomics better represents real-time physiological processes, urine provides higher sensitivity for detecting subtle biochemical changes. Compared with feces, urine has lower matrix complexity, simpler extraction, and fewer microbial contaminants, making it ideal for quantitative LC–MS urine metabolomics or NMR profiling.

What Types of Metabolites Are Detectable in Urine

The urinary metabolome encompasses thousands of compounds, including amino acids, organic acids, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bile acids (BAs), steroids, and xenobiotics. These metabolites originate from host pathways (energy metabolism, hormone synthesis) and microbiome-derived transformations such as indoles, hippurate, and phenolic derivatives. This chemical diversity makes urine a valuable biofluid for studies spanning nutrition, toxicology, and metabolic disease.

Confounders: Hydration, Diet, Circadian Rhythm, Menstrual Cycle, Medications

Despite its advantages, urine composition is highly dynamic. Hydration and fluid intake dilute or concentrate metabolites, while diet and circadian rhythms alter metabolic flux. Hormonal variations and medications also influence urinary excretion patterns. To ensure data reliability, consistent sampling—preferably first-morning urine—and creatinine normalization are recommended to correct for variability and improve cross-sample comparability in urine metabolite testing.

Figure 1. Distribution of metabolite classes in the human urine metabolome compared with other biofluids.

Source: Bouatra S, Aziat F, Mandal R, et al. “The Human Urine Metabolome.” PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e73076. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073076. Reused under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). No endorsement implied.

Urine Metabolomics Study Design & Sample Collection Best Practices

First-Morning vs Spot vs 24-Hour: When to Choose Which

Choosing the right collection type is essential for reproducible urine metabolomics results. First-morning urine is preferred for metabolomics because it is concentrated, reflects overnight metabolism, and reduces variation from diet or hydration. Spot urine is convenient for large studies but needs creatinine normalization to correct dilution. Twenty-four-hour collections capture total excretion, useful for renal or pharmacokinetic research, but are logistically demanding. Choose based on study aim, balancing precision and feasibility.

Preservatives, Storage, Freeze–Thaw, Aliquots

Collect urine into sterile tubes, keep on ice, and freeze at −80 °C within two hours. Avoid preservatives unless validated for the assay. Use aliquots to prevent repeated freeze–thaw cycles and ship on dry ice to maintain integrity. Consistent handling safeguards metabolite stability across samples.

Blinding, Replicates, Power Tips

Randomize and blind samples to reduce bias. Include technical and biological replicates to assess variability. Plan statistical power before data collection to ensure meaningful results. Implement pooled QCs throughout runs for performance monitoring. Careful design and standardized workflows are essential for robust and reproducible urine metabolomics outcomes.

Normalization Strategies for Urine Metabolomics Data

Urine concentration varies widely among individuals and time points, making normalization essential for meaningful urine metabolomics data. The goal is to correct for dilution effects so that observed differences in metabolites in urine reflect biology, not hydration.

Creatinine Normalization: Pros & Pitfalls

The most common approach expresses metabolites relative to creatinine concentration. It works well in healthy subjects because creatinine excretion is steady. However, it may bias results in CKD, elderly, or low–muscle-mass participants, where creatinine production is reduced.

Specific Gravity & Osmolality: When Hydration Varies Widely

These physical measures reflect total solute content and are valuable when hydration status fluctuates strongly—such as in field or pediatric studies. They’re less affected by muscle mass but require calibrated refractometry or osmometry.

Probabilistic Quotient Normalization (PQN) for Untargeted Datasets

PQN is a post-acquisition scaling method used in untargeted LC–MS urine metabolomics. It adjusts spectra by referencing each sample to a median profile, effectively correcting global dilution or signal drift without external markers.

To help select the most appropriate normalization method for your urine metabolomics workflow, the table below summarizes the key options at a glance:

|

Normalization Method |

Best Use Case |

Strengths |

Limitations |

Recommended Practice |

|

Creatinine |

Clinical and adult cohorts |

Simple, well established |

Biased by CKD, sex, muscle mass |

Use with renal health check and parallel QC |

|

Specific Gravity |

Field studies, variable hydration |

Fast, noninvasive |

Needs instrument calibration |

Ideal for pediatric or hydration-sensitive studies |

|

Osmolality |

Quantitative hydration control |

Reflects total solute load |

Affected by temperature |

Apply when precise solute normalization required |

|

PQN |

Untargeted datasets |

Corrects signal drift, scalable |

No biological context |

Combine with biological normalization for best results |

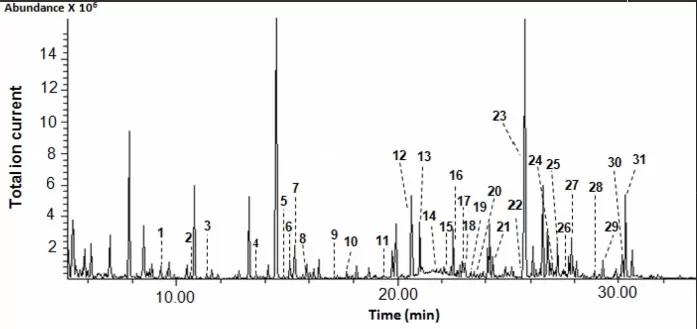

Analytical Platforms & Coverage in Urine Metabolomics

LC–MS urine metabolomics provides the widest metabolite coverage, GC–MS excels for volatiles and derivatizable acids, while NMR urine analysis offers unmatched reproducibility and quantitation. Combining multiple platforms yields a more complete urine metabolome view across chemical classes and biological pathways.

Targeted LC–MS/MS Panels (SCFAs, Amino Acids, Bile Acids, Tryptophan, Steroids)

Targeted LC–MS/MS quantifies predefined metabolites with isotope-labeled internal standards, achieving low LOD/LOQ and strong linearity. Typical urine metabolite test panels include SCFAs and organic acids (energy/microbiome readouts), amino acids and derivatives (nitrogen metabolism), bile acids (liver–gut axis), tryptophan–kynurenine–indole pathways (microbiome/immune crosstalk), and steroid hormones/catabolites (endocrine status). Use targeted panels for validation, clinical translation, and longitudinal monitoring where precision is critical.

Untargeted LC–HRMS (DDA/DIA; ESI±; Libraries & In-Silico)

Untargeted LC–HRMS profiles thousands of features across ESI+ and ESI–, capturing unexpected urinary metabolites and xenobiotics. DDA supports clean MS/MS libraries; DIA boosts coverage and reproducibility for discovery cohorts. Identification leverages spectral libraries, retention-time rules, and in-silico fragmentation, then rolls up to pathway-level enrichment to reveal biological mechanisms.

NMR: Reproducibility & Absolute Quantitation Trade-Offs

NMR urine profiling quantifies tens to ~100 abundant metabolites with exceptional run-to-run stability and straightforward absolute units—ideal for large cohorts, biobanks, and harmonized multi-site studies. Sensitivity is lower than LC–MS (fewer low-abundance hits), but matrix effects are minimal and batch correction is simpler. In practice, pair NMR for robust baseline quantitation with LC–MS/GC–MS to deepen pathway coverage (including volatiles) and capture rare biomarkers.

To summarize the strengths and trade-offs of each urine metabolomics platform:

|

Platform |

Key Features |

Strengths |

Limitations |

Best Application |

|

LC–MS / LC–MS/MS |

Broad metabolite coverage (polar to semi-polar), high sensitivity |

Detects low-abundance biomarkers; versatile for targeted & untargeted workflows |

Matrix effects, instrument variability |

Discovery and validation studies, targeted panels |

|

GC–MS |

Volatile and derivatized metabolites |

Excellent reproducibility; strong for organic acids & xenobiotics |

Requires derivatization; limited to volatile compounds |

Environmental & exposomic profiling, SCFA analysis |

|

NMR |

Quantitative and highly reproducible spectra |

Absolute quantitation; minimal matrix effects; easy standardization |

Lower sensitivity; fewer detected metabolites |

Cohort-scale studies, clinical metabolite reference building |

Quality Control and Data Integrity in Urine Metabolomics

High-quality urine metabolomics data relies on strict and consistent QC procedures. These controls ensure that changes in urinary metabolites reflect true biology rather than analytical drift or sample handling issues. Key QC methods include:

- Internal Standards (IS): Stable-isotope–labeled compounds added to each sample to monitor extraction efficiency, injection consistency, and instrument performance.

- Pooled QC Samples: A composite urine sample injected regularly (e.g., every 5–10 samples) to track signal drift, retention-time stability, and overall reproducibility across the batch.

- Blanks (Solvent / Procedural): Identify contaminants, carryover, or background noise introduced during sample prep or LC–MS runs.

- Randomization: Random sample run order to avoid systematic batch or time-dependent bias.

- Feature Filtering: Removal of metabolites with high CV in QCs, unstable retention times, or low signal quality.

Using multiple QC layers ensures that urine metabolite test results are robust, comparable across batches, and suitable for downstream biological interpretation.

Kidney and Urological Applications of Urine Metabolomics

Urine directly reflects glomerular filtration and tubular reabsorption, making urine metabolomics a powerful tool for renal and urological research. Altered levels of amino acids, organic acids, and acylcarnitines in the urine metabolome can signal early tubular injury or impaired filtration before serum markers change.

Recent high-impact studies show strong predictive value. A recent genome-wide association study of 54 urinary metabolites identified 33 novel genetic loci linked to kidney function and chronic kidney disease, highlighting how urinary metabolomics complements traditional markers such as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) for risk stratification.

Applications extend to urological conditions. Untargeted LC–MS profiling has identified metabolic fingerprints for bladder cancer, interstitial cystitis, and nephrolithiasis. In a 2024 study, urine metabolomics detected UTIs by identifying microbe-derived metabolites such as agmatine with AUC > 0.95, enabling culture-independent, rapid diagnostics.

Overall, urinary metabolites offer early, non-invasive indicators for CKD, AKI, kidney transplant monitoring, and bladder pathology—supporting both mechanistic insight and clinical screening.

Nutritional and Microbiome-Derived Signatures in the Urine Metabolome

Diet and the gut microbiome strongly shape the urine metabolome, making urine an objective matrix for nutritional assessment and host–microbe interaction studies. Polyphenol-rich diets increase excretion of benzoic acid, phenolic acids, and other antioxidant metabolites, whereas Western diets elevate markers of oxidative stress.

Microbiome-derived metabolites provide particularly rich information. Hippurate, indoxyl sulfate, p-cresol sulfate, and TMAO appear consistently in urine when the gut microbiota is active. Controlled feeding studies show a sharp decline in hippurate under microbiome depletion, confirming its microbial origin.

Urine metabolomics also distinguishes dietary patterns, including fiber intake, protein load, and choline-rich foods. In a 2024 controlled intervention, antioxidant-enriched diets shifted urinary pathways related to inflammation, methylation, and lipid oxidation.

Because urine integrates both dietary exposures and microbial metabolism, urinary metabolites serve as sensitive readouts for nutrition research, personalized diet evaluation, and microbiome-driven metabolic health.

Toxicological and Occupational Exposure Biomarkers in Urine Metabolomics

The urine metabolome captures both endogenous metabolism and absorbed environmental chemicals, enabling non-invasive detection of toxic exposures. Workers exposed to metals or solvents show consistent perturbations in oxidative stress and mitochondrial pathways detectable in untargeted urine metabolomics.

Firefighters represent a well-studied example: post-fire urine samples reveal elevated hippuric acid, TMAO, indole derivatives, and hormone catabolites, reflecting smoke inhalation, toxin load, and acute stress response. More than 200 exposure-associated metabolites have been identified in recent LC–HRMS analyses.

Emerging evidence also links vaping exposure to distinct urinary metabolic shifts. E-cigarette users excrete higher levels of diethyl phthalate, flavoring chemicals, and altered acylcarnitine profiles, suggesting lipid and oxidative stress pathways are affected.

Urine metabolomics can detect pesticides, phthalates, BPA metabolites, and other xenobiotics long before clinical symptoms appear. As an unbiased screening tool, urine metabolite tests support exposomics, occupational monitoring, and environmental health surveillance.

Using Urinary Metabolites for Stress and Endocrine Monitoring

Urine provides an integrated view of hormonal output, making it ideal for monitoring stress physiology through urinary metabolites. Cortisol, cortisone, tetrahydrocortisol, and related steroid catabolites are excreted continuously, offering better temporal integration than single serum measurements.

Metabolomics studies of burnout, shift work, and chronic stress show consistent alterations in steroid pathways, catecholamine breakdown (VMA, HVA), and long-chain acylcarnitines. A 2025 healthcare-worker study identified disrupted cortisol–cortisone metabolism and impaired tryptophan–serotonin pathways in high-burnout individuals.

The approach extends beyond psychological stress. Urine metabolomics detects endocrine disorders such as Cushing’s disease, adrenal insufficiency, and thyroid dysfunction by profiling steroid and energy-related metabolites. Serial urine sampling allows circadian hormone rhythm mapping without invasive collection.

Overall, urine metabolomics offers a sensitive, non-invasive window into HPA-axis function, catecholamine turnover, and endocrine dysregulation—supporting both research and clinical hormone monitoring.

FAQs About Urine Metabolomics and Urinary Metabolites

Q1. What is urine metabolomics?

Urine metabolomics is the comprehensive profiling of urinary metabolites using LC–MS, GC–MS or NMR to characterize the urine metabolome. It is used to discover biomarkers related to diet, microbiome, kidney function, exposure, and disease.

Q2. What types of metabolites can a urine metabolite test detect?

A urine metabolite test can measure amino acids, organic acids, SCFAs, bile acids, steroids, vitamins, xenobiotics, and many microbiome-derived compounds. Coverage depends on the platform and whether the method is targeted or untargeted.

Q3. When should I collect first-morning vs random urine?

First-morning urine is preferred for most urine metabolomics studies because it is more concentrated and less affected by recent diet or hydration. Random (spot) urine is acceptable for large cohorts but requires careful normalization.

Q4. How is dilution handled in urine metabolomics data?

Most studies use creatinine normalization to correct for urine dilution, especially in adult cohorts. Specific gravity, osmolality, and PQN are additional strategies used in untargeted urine metabolomics workflows.

Q5. How is urine metabolomics different from blood metabolomics?

Blood reflects tightly regulated, real-time circulating metabolism, whereas urine captures excreted end-products, toxins, and many microbiome-derived metabolites. For non-invasive, repeated sampling and exposomics, the urine metabolome is often preferable.

Q6. What is the difference between targeted and untargeted urine metabolomics?

Targeted LC–MS urine metabolomics quantifies a defined panel of metabolites with high precision. Untargeted LC–HRMS screens thousands of features in the urine metabolome for discovery of new biomarkers and pathways.

Get Started with Urine Metabolomics and Urine Metabolite Testing

Urine metabolomics unlocks detailed insights into metabolism, kidney function, diet, microbiome, and exposure using LC–MS–based untargeted and targeted metabolomics. Our team supports projects from early study design to data interpretation, including advice on sample volume, collection tubes, stabilization, and shipping for urine samples.

We offer LC–MS untargeted urine metabolomics for broad pathway discovery, and targeted urine metabolite panels (e.g., organic acids, SCFAs, amino acids, bile acids, tryptophan pathway, steroids) for precise quantification and validation. Contact us to discuss your study goals, choose an appropriate urine metabolomics workflow, and turn urinary metabolite profiles into clear, actionable results.

Reference

- Balhara N, Devi M, Balda A, Phour M, Giri A. Urine; a new promising biological fluid to act as a non-invasive biomarker for different human diseases. Urine. 2023;5(1):40–52. doi:10.1016/j.urine.2023.06.001.

- Weldon KC, Panitchpakdi M, Caraballo-Rodríguez AM, et al. Urinary Metabolomic Profile is Minimally Impacted by Common Storage Conditions and Additives. Int Urogynecol J. 2025;36(4):839-847. doi:10.1007/s00192-025-06069-2

- Jeppesen MJ, Powers R. Multiplatform untargeted metabolomics. Magn Reson Chem. 2023;61(12):628-653. doi:10.1002/mrc.5350

- Khodadadi M, Pourfarzam M. A review of strategies for untargeted urinary metabolomic analysis using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Metabolomics. 2020;16(6):66. Published 2020 May 18. doi:10.1007/s11306-020-01687-x

- Sun J, Xia Y. Pretreating and normalizing metabolomics data for statistical analysis. Genes Dis. 2023;11(3):100979. Published 2023 Jul 7. doi:10.1016/j.gendis.2023.04.018

- González-Domínguez Á, Estanyol-Torres N, Brunius C, Landberg R, González-Domínguez R. QComics: Recommendations and Guidelines for Robust, Easily Implementable and Reportable Quality Control of Metabolomics Data. Anal Chem. 2024;96(3):1064-1072. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.3c03660

- Broeckling CD, Beger RD, Cheng LL, et al. Current Practices in LC-MS Untargeted Metabolomics: A Scoping Review on the Use of Pooled Quality Control Samples. Anal Chem. 2023;95(51):18645-18654. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.3c02924

- Jiang X, Liu X, Qu X, et al. Integration of metabolomics and peptidomics reveals distinct molecular landscape of human diabetic kidney disease. Theranostics. 2023;13(10):3188-3203. Published 2023 May 21. doi:10.7150/thno.80435

- Valo E, Richmond A, Mutter S, et al. Genome-wide characterization of 54 urinary metabolites reveals molecular impact of kidney function. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):325. Published 2025 Jan 2. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-55182-1

- Singh D, Ham D, Kim SA, et al. Urine metabolomics unravel the effects of short-term dietary interventions on oxidative stress and inflammation: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):15277. Published 2024 Jul 3. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-65742-6

- Furlong MA, Liu T, Snider JM, et al. Evaluating changes in firefighter urinary metabolomes after structural fires: an untargeted, high resolution approach. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):20872. Published 2023 Nov 27. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-47799-x

- Siwakoti RC, Iyer G, Banker M, et al. Metabolomic Alterations Associated with Phthalate Exposures among Pregnant Women in Puerto Rico. Environ Sci Technol. 2024;58(41):18076-18087. doi:10.1021/acs.est.4c03006

- Lu P, He R, Wu Y, et al. Urinary metabolic alterations associated with occupational exposure to metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons based on non-target metabolomics. J Hazard Mater. 2025;487:137158. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.137158

- Cavalier H, Long SE, Rodrick T, et al. Exploratory untargeted metabolomics analysis reveals differences in metabolite profiles in pregnant people exposed vs. unexposed to E-cigarettes secondhand in the NYU children's health and environment study. Metabolomics. 2025;21(4):92. Published 2025 Jun 26. doi:10.1007/s11306-025-02280-w

- Vogg N, Müller T, Floren A, et al. Targeted metabolic profiling of urinary steroids with a focus on analytical accuracy and sample stability. J Mass Spectrom Adv Clin Lab. 2022;25:44-52. Published 2022 Jul 25. doi:10.1016/j.jmsacl.2022.07.006

- Bouatra S, Aziat F, Mandal R, et al. The human urine metabolome. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73076. Published 2013 Sep 4. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073076

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.