Cell Surface Proteomics (Surfaceome) Guide: Definition, Workflow, and Translational Applications

Imagine if we could read a cell’s ID card, understand its job description, and even predict its next move—all by examining its outer surface. This is not science fiction, but the tangible promise of cell surface proteomics. Every cell in our body communicates, senses its environment, and defines its identity through a dynamic layer of proteins on its membrane. This intricate “surfaceome” holds the keys to revolutionary advancements in disease diagnosis, drug development, and personalized medicine. In this comprehensive guide, we will demystify this critical cellular frontier, exploring fundamental role in modern biomedical research, its indispensable contributions to understanding cellular function, and how cutting-edge technologies are unlocking its secrets to power the next generation of therapeutic breakthroughs.

1. What is Cell Surface Proteomics? Decoding the Cellular “Social Network”

At the heart of cellular identity and communication lies a specialized set of molecules acting as the cell’s interface with the world. Cell surface proteomics is the systematic, large-scale study of this very interface—the “surfaceome.” This chapter will define this crucial cellular compartment and explore its fundamental components, setting the stage for understanding its immense biological and clinical significance.

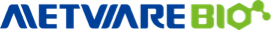

Schematic representation of different membrane protein types.

Image reproduced from de Jong and Koker, 2023, Membranes, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

1.1 Core Definition: The Cellular “Interface” and “Identity”

The cell surface proteome, or surfaceome, is defined as the complete set of proteins located on the exterior of the plasma membrane, featuring domains accessible to the extracellular space. It constitutes the primary physical and functional boundary through which a cell interacts with neighboring cells, the extracellular matrix, signaling molecules, pathogens, and drugs (Bausch-Fluck, Hofmann, & Wollscheid, 2012). Far from being a static shell, this protein layer is a dynamic, information-rich network that defines cellular function and state. The surfaceome is composed of several key protein classes, each playing a distinct role in cellular life:

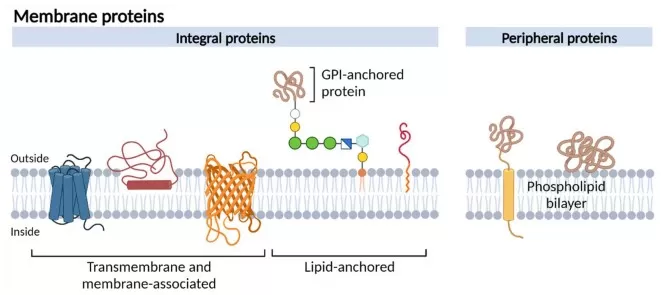

- Receptors: Such as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), these proteins act as molecular antennas, receiving hormonal, growth factor, and cytokine signals to trigger intracellular cascades.

- Adhesion Molecules: Including integrins and cadherins, they mediate critical cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, ensuring tissue integrity, facilitating immune responses, and guiding cell migration.

- Transporters and Channels: These proteins regulate the precise flow of ions, nutrients, and other molecules across the membrane, maintaining cellular homeostasis.

- Enzymes: Ecto-enzymes on the cell surface catalyze localized reactions, playing roles in signal modulation, extracellular matrix remodeling, and metabolite processing.

- Structural Proteins: They help organize membrane microdomains, such as lipid rafts, and provide physical stability to the cell surface architecture.

Membrane Protein Functions.

Image created with Biorender by Samara Ona, source link: https://www.biorender.com/template/membrane-protein-functions

1.2 The Dynamic and Complex Nature of the Surfaceome

Understanding the surfaceome requires appreciating its inherent complexity and dynamism. It is not a fixed entity but a highly regulated compartment that remodels itself in response to a multitude of cues. This plasticity is central to both normal physiology and disease.

The composition of the surfaceome is precisely regulated by the cell’s developmental stage, cell cycle phase, metabolic status, and disease condition (e.g., cancer or inflammation). External factors, including drug treatments, mechanical forces, and signals from the microenvironment, can also trigger rapid reshuffling of surface proteins (Di Meo e al., 2024). This allows a cell to adapt its “social profile” instantly—like changing its wardrobe for different occasions—to respond to threats, communicate new needs, or assume a specialized function. However, this very dynamism and diversity present significant technical challenges for researchers. Surface proteins are often of low abundance, embedded in a hydrophobic lipid environment, and exist in diverse forms (transmembrane, GPI-anchored), making their comprehensive isolation and analysis a non-trivial feat that requires specialized methodologies.

2. Why Study Cell Surface Proteomics? The Gateway to Biomarker and Drug Discovery

Having established the surfaceome as the dynamic “social interface” of the cell, a pivotal question emerges: why does it warrant dedicated, systematic investigation? The answer lies in its unparalleled translational value. This chapter will delve into why surface proteomics is far more than an analytical technique; it is a strategic bridge connecting fundamental biological discovery to next-generation clinical applications, serving as the essential gateway in biomarker and drug discovery.

2.1 The Unrivaled “Druggability” and Accessibility of Surface Proteins

The foremost principle in drug development is that a target must be accessible. In this fundamental attribute, cell surface proteins possess a natural, insurmountable advantage over intracellular targets, making them a goldmine for therapeutic intervention. It is estimated that over 60% of current drug targets are membrane proteins, predominantly located on the cell surface. This is because the extracellular domains of surface proteins are directly accessible to therapeutic antibodies, small molecules, peptide therapies, and advanced cellular therapeutics like CAR-T (Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell) therapy, without the need to overcome complex intracellular delivery barriers. This direct accessibility significantly simplifies drug design and increases the probability of successful development. For example, many cancer therapies aim to target surface receptors that are overexpressed or mutated in tumor cells. Targeting these proteins can disrupt the processes that drive cancer cell proliferation and metastasis.

Furthermore, surface proteins are ideal sources for clinical biomarkers. Due to their exterior location, surface proteins or their shed extracellular domains (e.g., soluble receptors) can be released into circulation (e.g., blood, cerebrospinal fluid). This enables non-invasive or minimally invasive detection through techniques like liquid biopsy, providing a convenient molecular window for early disease diagnosis, prognosis, and real-time treatment monitoring.

2.2 The Surfaceome As Cellular “Command Center” and Information Hub

If “accessibility” is the formal advantage, the role of surface proteins as master regulators of cellular function constitutes their indispensable intrinsic value.

The surfaceome acts as the master regulator of cellular decision-making, serving as the starting point for nearly all signal transduction pathways. Virtually all cellular responses—including growth, differentiation, migration, metabolic reprogramming, and programmed cell death—are triggered when surface receptors receive extracellular signals. Targeting these receptors allows for intervention at the very apex of signaling cascades, enabling efficient and specific alteration of cell behavior in a way that targeting downstream intracellular components often cannot.

As the cell's most sensitive window to the environment, the surfaceome also provides a real-time "molecular barcode" of cellular health. The expression profile, post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation), and spatial conformation of the surfaceome undergo rapid and specific reprogramming in response to cell type, activation status, metabolic stress, and disease progression. Therefore, the surfaceome serves as an up-to-the-minute reflection of cellular physiology and pathology, offering the most direct means to accurately identify specific cell subsets, such as cancer stem cells or exhausted T cells. This heightened sensitivity enables researchers to detect the earliest molecular signatures of disease before any significant phenotypic changes occur.

3. How to Capture and Decode the Elusive Surfaceome? The Complete Workflow of Cell Surface Proteomics

Understanding the immense value of the surfaceome naturally leads to the pivotal question: how do we capture and decode this elusive proteome? A successful surface proteomics project is a multi-stage endeavor that hinges on the seamless integration of strategic design, precise wet-lab techniques, advanced mass spectrometry, and specialized bioinformatics. Each step must be carefully optimized to maximize protein recovery, specificity, and accuracy, while minimizing contamination or loss of important proteins. This chapter provides a clear, step-by-step roadmap, demystifying the complete workflow from initial sample preparation to final biological insight.

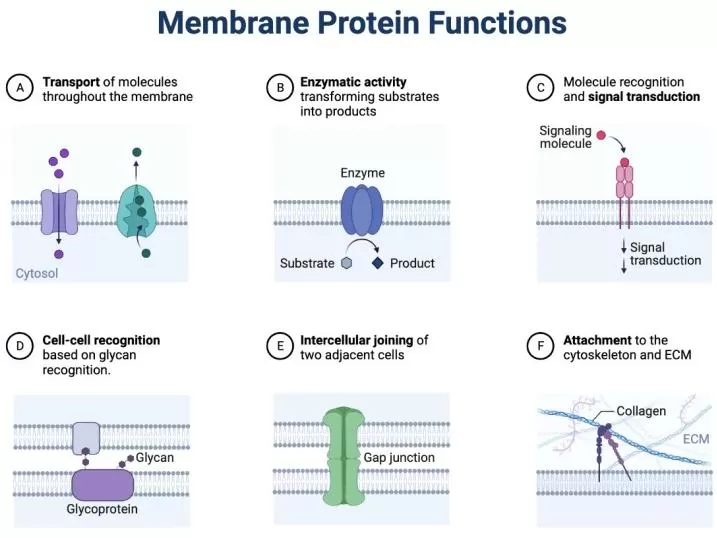

Profiling cell surface sialoglycoproteins via the bio-orthogonal chemical reporter strategy combined with quantitative shotgun proteomics.

Image reproduced from Autelitano et al., 2014, PloS one, licensed under the Creative Commons CC0.

3.1 Sample Selection and Preparation

Sample preparation is one of the most critical stages in the cell surface proteomics workflow. The quality of the sample directly influences the success of subsequent enrichment, analysis, and interpretation. In surface proteomics, common sample types include adherent cells, suspension cells, tissue samples, and extracellular vesicles (EVs). Each type requires different preparation methods:

i. Adherent Cells: Cells grown on surfaces must be carefully detached without damaging surface proteins. Enzymatic dissociation or mechanical scraping can be used, but these methods need to be optimized to avoid excessive disruption.

ii. Suspension Cells: These cells are more easily processed, as they do not require detachment. However, they may still present challenges in terms of surface protein recovery.

iii. Tissue Samples: For tissue samples, careful homogenization and enrichment protocols are needed to isolate specific cell types and avoid contamination from other tissue components.

iv. Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): These tiny vesicles, which carry surface proteins, require specialized isolation methods, such as ultracentrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography.

To ensure that proteins remain intact and functional during the preparation process, it is essential to maintain sample viability and prevent degradation. Proper handling includes keeping the samples on ice, using protease inhibitors to prevent protein degradation, and processing the samples quickly to reduce any changes in protein expression that could affect downstream analyses.

3.2 Targeted Enrichment of Surface Proteins

Targeted enrichment of surface proteins is a critical step in surface proteomics, enabling researchers to isolate cell surface proteins of interest from complex samples. The goal is to capture a highly specific set of surface proteins while minimizing contamination from intracellular proteins. To achieve this, several enrichment strategies based on different principles are used, each with its own advantages and challenges.

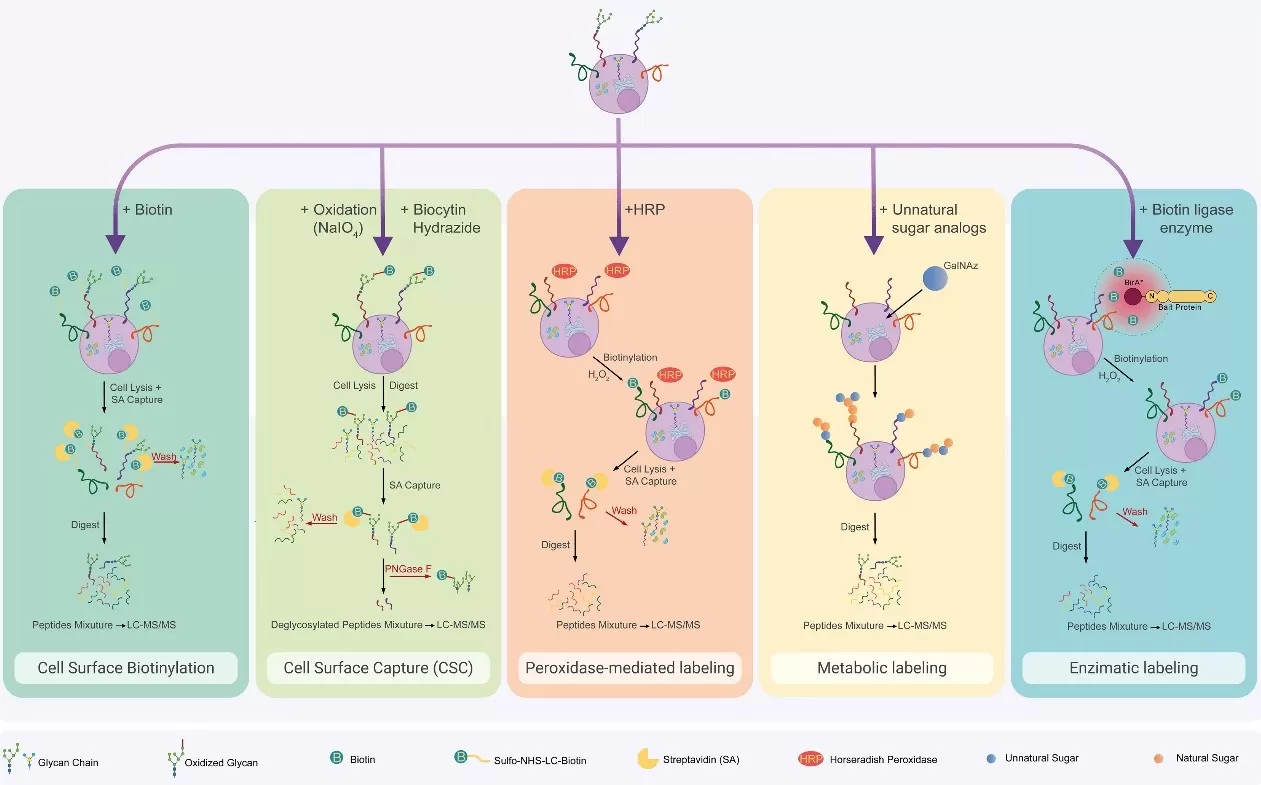

Surfaceome chemical enrichment methods. Cell surface biotinylation

Image reproduced from Di Meo et al., 2024, Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy

3.2.1. Chemical Tag-Based Enrichment (Biotinylation)

Chemical tag-based enrichment, particularly biotinylation, involves labeling surface proteins with membrane-impermeable biotinylation reagents, which attach to the extracellular domains of the proteins. These biotinylated proteins can then be captured using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads, ensuring specific enrichment of surface proteins while minimizing intracellular contamination. This method is widely used for large-scale surface proteomics studies across different cell types and samples. Its main advantages are high specificity, efficiency, and broad applicability. However, it can have limitations, such as incomplete labeling or difficulty accessing certain membrane proteins, which may affect the capture of some surface proteins.

Biotinylation-based enrichment involves three key steps: labeling, capture, and stringent washing & elution.

1) Labeling: The first step is to covalently label surface proteins with a membrane-impermeable biotinylation reagent. Optimizing the reagent concentration and incubation time is crucial to ensure efficient labeling while avoiding cellular stress that could affect protein expression.

2) Capture: After labeling, cells are lysed to release proteins. Lysis should be gentle enough to maintain the integrity of surface proteins while breaking down the cell membrane. Biotinylated surface proteins are then isolated using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads, ensuring high specificity for surface proteins and minimal intracellular contamination.

3) Stringent Washing & Elution: A series of stringent washes removes non-specifically bound proteins. Biotinylated proteins are then eluted, typically by cleaving the disulfide linker in the reagent using a reducing agent like DTT.

One key technical challenge is optimizing the "purity vs. yield" balance. Overly stringent washing can reduce the recovery of low-abundance surface proteins, while insufficient washing may lead to cytoplasmic contamination. Protocols must be tailored to the sample type, and quality control measures, such as Western blotting for known surface and intracellular markers, are essential to ensure enrichment specificity.

3.2.2. Immunoaffinity-Based Enrichment

Immunoaffinity-based enrichment uses antibodies specific to surface proteins or their extracellular domains to isolate the target proteins. These antibodies are typically conjugated to magnetic beads, allowing for the selective capture of the surface proteins. This method is ideal for targeted studies where specific surface proteins or families of proteins are of interest. It provides high specificity and can be used for both broad or focused enrichment. However, its main drawbacks include the availability of high-quality antibodies and the potential for non-specific binding, which can introduce contamination. Despite these challenges, it remains a powerful tool for studying known surface proteins with precision.

3.2.3 Other Enrichment Methods

In addition to biotinylation and immunoaffinity-based techniques, emerging methods like Mass Cytometry (CyTOF) and Cell Surface Capture (CSC) provide new ways to enrich and analyze surface proteins. CyTOF uses metal-labeled antibodies to profile multiple surface proteins at the single-cell level, offering high-dimensional data that reveals cellular heterogeneity and is especially useful in immunology and cancer research. CSC, on the other hand, leverages affinity reagents such as lectins to capture a broad spectrum of surface proteins, allowing for comprehensive proteomic analysis. These methods are highly advantageous for large-scale, high-throughput studies and single-cell resolution, but they come with the challenges of complexity, specialized equipment, and higher costs. Despite these limitations, they expand the analytical capabilities of surface proteomics, enabling more detailed and comprehensive investigations.

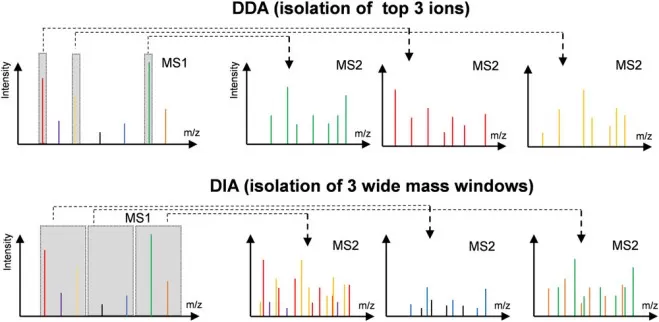

3.3 Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Once surface proteins are enriched, they are digested into smaller peptides using enzymes like trypsin, which facilitates their analysis by mass spectrometry (MS). Peptides are then separated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) based on hydrophobicity before being ionized and analyzed in the mass spectrometer. MS acquisition can be performed in two main modes: Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA), where the most abundant peptides are selected for fragmentation, and Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA), which collects all ions in a predefined mass range for more reproducible quantification. Protein quantification can be achieved using label-based techniques such as Tandem Mass Tags (TMT) or Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantification (iTRAQ), or label-free methods that rely on ion intensity. Each approach has its advantages depending on the experimental goals and design.

Difference in MS1 isolation windows for the DDA and DIA modes.

Image reproduced from Tian, X., Permentier, H. P., Bischoff, R, 2023, Mass spectrometry reviews, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

3.4 Bioinformatics & Data Interpretation

After mass spectrometry analysis, the complex MS data is processed using specialized bioinformatics pipelines to identify and quantify proteins. Software tools like MaxQuant or Spectronaut match MS/MS spectra against protein databases to identify peptides and infer protein identities. Quantitative data is extracted, normalized, and subjected to statistical analysis to determine significant differences across conditions.

A critical step in surface proteomics is filtering proteins for their likelihood of being true surface proteins. Bioinformatics tools such as TMHMM (for transmembrane helices), SignalP (for signal peptides), and PredGPI (for GPI-anchors) help predict membrane integration or secretion motifs, distinguishing surface proteins from intracellular ones. After identifying a high-confidence list of surface proteins, functional annotation is performed using Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment to uncover biological roles. Additionally, protein-protein interaction network analysis helps identify clusters of co-regulated surface proteins, providing insights into key cellular processes. Finally, independent validation techniques like flow cytometry, immunofluorescence, or Western blotting are employed to confirm the surface localization and expression of candidate proteins in new biological samples.

4. From Discovery to Therapy: Transformative Applications of Cell Surface Proteomics

The true power of cell surface proteomics is realized in its transformative applications. By providing a systematic map of the cellular exterior, this technology moves beyond basic science to directly impact drug discovery, therapeutic development, and our understanding of disease mechanisms. This chapter explores key applications through recent case studies, demonstrating how surfaceome data is being translated into tangible advances in biomedicine.

4.1 Precision Oncology & Biomarker Discovery

Cell surface proteomics has become a cornerstone in precision oncology by enabling the unbiased discovery of tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) and clinically actionable biomarkers. Using advanced mass spectrometry enrichments of the surfacome, researchers can directly quantify differential expression of surface proteins between tumors and normal cells, revealing proteins uniquely or highly expressed on cancer cell surfaces. For example, plasma membrane profiling of primary multiple myeloma cells led to the identification of semaphorin-4A (SEMA4A), a surface protein not previously implicated in myeloma biology, as a highly specific target. Functional follow-up demonstrated that antibody–drug conjugates targeting SEMA4A selectively killed myeloma cells in vitro and in vivo (Anderson et al., 2022), illustrating how surface proteomics directly yields biomarkers tied to cellular physiology and therapeutic consequence. These discoveries not only advance tumor subclass stratification but also enable detection of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and predictive biomarkers for treatment response, feeding into liquid biopsy strategies and personalized therapeutic decisions.

4.2 Drug Target Discovery and Validation

Surface proteomics accelerates druggable target identification by systematically comparing the cell surface protein landscape of diseased versus healthy cells, revealing high-value receptors and transporters suitable for pharmacological modulation. This approach places special emphasis on protein classes that are inherently targetable, such as GPCRs, ion channels, and membrane transporters, which comprise a disproportionate share of clinically successful drug targets. Through quantitative membrane proteomics, researchers have mapped thousands of cell surface proteins on RAS-driven cancer cells, identifying upregulated surface proteins like CDCP1 that are selectively enriched on mutant cells and validated as actionable targets. Subsequent antibody development against CDCP1 demonstrated preclinical efficacy, underscoring how surfacome profiling can prioritize drug targets that are both disease-specific and amenable to therapeutic intervention (Ye et al., 2024). This strategy enhances the efficiency of drug development pipelines by focusing on surface proteins with favorable expression patterns and functional relevance, improving the chance of translating basic discoveries into clinical candidates.

4.3 Next–Generation Biotherapeutics: ADCs and Cell Therapies

Cell surface proteomics has emerged as a strategic enabler for next-generation biotherapeutics such as antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and CAR-T/TCR-T cell therapies by informing antigen selection and design optimization. ADC efficacy depends on selecting surface antigens that are abundant on tumor cells but minimally expressed on normal tissues to maximize specificity and reduce toxicity. Surfaceome profiling generates high-resolution antigen expression maps that guide the choice of ADC targets and help refine linker and payload strategies. Similarly, for adoptive cell therapies, surfacome data identifies optimal targets for chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) with sufficient tumor specificity and minimal off-tumor engagement. Comprehensive reviews of surface proteomics-aided target discovery highlight how profiling approaches, including quantitative MS and proximity labeling, accelerate the identification of CAR-T targets beyond canonical antigens and support design decisions based on expression patterns and structural context (Hosen, 2024). By anchoring therapeutic design in empirical surfaceome evidence, researchers improve the safety and efficacy profiles of engineered biologics.

4.4 Host–Pathogen Interactions and Infection Biology

In infection biology, cell surface proteomics provides deep insights into host–pathogen interactions by defining how pathogens engage and exploit host surface proteins during the infection cycle. Viral entry often hinges on specific interactions between viral proteins and host surface receptors, and comprehensive surfaceome analyses reveal both known and novel host factors that mediate attachment, entry, and immune evasion. Large-scale interactome studies combining affinity purifications and mass spectrometry have mapped hundreds of high-confidence interactions between SARS-CoV-2 proteins and human host proteins, illuminating how viral components interface with the cell’s proteomic landscape. Quantitative interactomes then serve as rational bases for identifying host factors that could be targeted for antiviral interventions, or as diagnostics for identifying infection-associated alterations in cell surface expression (Zhou et al., 2023). These surface proteomic and interactomic insights are critical for understanding pathogen tropism, uncovering vulnerability nodes in host cells, and ultimately informing the development of antiviral drugs and vaccines.

References:

1. de Jong, E., & Kocer, A. (2023). Current Methods for Identifying Plasma Membrane Proteins as Cancer Biomarkers. Membranes, 13(4), 409. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes13040409

2. Autelitano, F., Loyaux, D., Roudières, S., Déon, C., Guette, F., Fabre, P., Ping, Q., Wang, S., Auvergne, R., Badarinarayana, V., Smith, M., Guillemot, J. C., Goldman, S. A., Natesan, S., Ferrara, P., & August, P. (2014). Identification of novel tumor-associated cell surface sialoglycoproteins in human glioblastoma tumors using quantitative proteomics. PloS one, 9(10), e110316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110316

3. Bausch-Fluck, D., Hofmann, A., & Wollscheid, B. (2012). Cell surface capturing technologies for the surfaceome discovery of hepatocytes. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 909, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-61779-959-4_1

4. Di Meo, F., Kale, B., Koomen, J. M., & Perna, F. (2024). Mapping the cancer surface proteome in search of target antigens for immunotherapy. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy, 32(9), 2892–2904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.07.019

5. Tian, X., Permentier, H. P., & Bischoff, R. (2023). Chemical isotope labeling for quantitative proteomics. Mass spectrometry reviews, 42(2), 546–576. https://doi.org/10.1002/mas.21709

6. Anderson, G. S. F., Ballester-Beltran, J., Giotopoulos, G., Guerrero, J. A., Surget, S., Williamson, J. C., So, T., Bloxham, D., Aubareda, A., Asby, R., Walker, I., Jenkinson, L., Soilleux, E. J., Roy, J. P., Teodósio, A., Ficken, C., Officer-Jones, L., Nasser, S., Skerget, S., Keats, J. J., … Chapman, M. A. (2022). Unbiased cell surface proteomics identifies SEMA4A as an effective immunotherapy target for myeloma. Blood, 139(16), 2471–2482. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2021015161

7. Ye X. (2024). Quantitative Membrane Proteomics for Discovery of Actionable Drug Targets at the Surface of RAS-Driven Human Cancer Cells. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 2823, 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-3922-1_3

8. Hosen N. (2024). Identification of cancer-specific cell surface targets for CAR-T cell therapy. Inflammation and regeneration, 44(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41232-024-00329-2

9. Zhou, Y., Liu, Y., Gupta, S., Paramo, M. I., Hou, Y., Mao, C., Luo, Y., Judd, J., Wierbowski, S., Bertolotti, M., Nerkar, M., Jehi, L., Drayman, N., Nicolaescu, V., Gula, H., Tay, S., Randall, G., Wang, P., Lis, J. T., Feschotte, C., … Yu, H. (2023). A comprehensive SARS-CoV-2-human protein-protein interactome reveals COVID-19 pathobiology and potential host therapeutic targets. Nature biotechnology, 41(1), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01474-0

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.