How to Choose the Right Proteomics Technology? A Decision Guide from Sample to Goal

Proteomics plays a pivotal role in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying diseases, cellular functions, and biological processes. However, selecting the appropriate proteomics technology for your research can be daunting due to the wide range of sample types, research objectives, and available methods. This guide provides a structured approach to navigating the complexities of proteomics technology selection, from understanding your sample to defining your research goals and choosing the most suitable technology.

1. Understand Your Sample Type and Its Challenges

The first crucial step in selecting the right proteomics technology is understanding the characteristics and challenges associated with your sample. Different sample types exhibit unique properties that necessitate specific methods for optimal proteomics analysis. Below, we discuss various sample types, their inherent challenges, and key considerations when selecting the most appropriate technology for analysis.

1.1 Sample Type: Challenges and Proteomics Methods

- Cell Lines: Cell lines are commonly utilized in proteomics due to their reproducibility and well-defined protein expression profiles. While these samples are relatively straightforward to work with, they present challenges in terms of sample complexity and the need for efficient protein extraction. DDA is typically employed for large-scale protein identification in cell lines, whereas DIA can be used for quantitative proteomics. However, while cell lines provide a relatively simple proteome, post-translational modifications (PTMs) and protein interactions can still introduce variability, necessitating careful data interpretation.

- Tissues: Tissue samples are inherently more complex, with considerable heterogeneity within different regions. This complexity makes protein extraction challenging, as the protein composition varies significantly between tissue types. Additionally, high-abundance proteins can overshadow low-abundance biomarkers. While DDA works well for discovery-driven studies in tissue samples, isobaric labeling (TMT/iTRAQ) is often employed for comparative analysis across multiple tissue types. DIA is especially valuable for large-scale or high-throughput studies involving tissue samples, providing reliable and reproducible quantification despite the tissue's complexity.

- Biofluids (Plasma, Serum, Urine): Biofluids, particularly plasma and serum, are among the most complex samples for proteomics due to their vast dynamic range of protein concentrations. Highly abundant proteins, such as albumin and immunoglobulins, can mask the detection of low-abundance proteins that are often critical biomarkers. To overcome this challenge, protein depletion strategies are commonly applied. DIA is frequently used to provide reproducible results in biofluid analysis, while targeted proteomics (PRM/SRM) is more suited to studying specific biomarkers in plasma or serum.

- Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): EVs are small membrane-bound vesicles secreted by cells, containing proteins, lipids, and RNA. Due to their low abundance and the difficulty in isolating EVs, specialized methods are required to analyze these low-input samples effectively. Microproteomics techniques, which focus on high sensitivity and minimizing sample loss, are ideal for working with EVs. For quantitative analysis of EV proteins, PRM or DIA are commonly employed, providing a reliable means to study the protein composition and alterations in EVs.

- Bacteria: Bacterial proteomics presents unique challenges due to the presence of a dense cell wall and the high abundance of certain proteins, such as ribosomal proteins, which can dominate the proteome. While bacterial proteomes are less complex than those of multicellular organisms, efficient protein extraction is critical. DDA is effective for discovery-driven bacterial proteomics, whereas DIA is useful for comparing bacterial strains or analyzing the response to different treatments.

1.2 Sample Quantity and Reproducibility

The amount of available sample significantly influences the choice of proteomics technology, particularly when working with low-input or rare samples. In cases such as tissue biopsies, single cells, or precious samples, it is essential to utilize methods that maximize the sensitivity and minimize sample loss during protein extraction. Detecting low-abundance proteins in small samples necessitates highly sensitive techniques.

For low-input samples, targeted proteomics methods like PRM/SRM are ideal due to their high sensitivity and the ability to quantify proteins with minimal starting material. Additionally, microproteomics approaches are highly effective for small sample volumes, focusing on optimizing protein extraction while minimizing sample loss. These methods are particularly useful when dealing with limited quantities, allowing researchers to analyze proteins even from small or rare samples.

Reproducibility is another critical factor in proteomics studies, especially when working with rare or clinical samples. Variability in sample collection, preparation, or storage can lead to inconsistent results. Establishing highly optimized sample preparation protocols that minimize loss and ensure reproducible outcomes across replicates is key to ensuring reliable results.

2. Define Your Research Goals: Qualitative vs Quantitative Proteomics

Once you understand your sample, the next step is to define your research goals. Are you focused on identifying proteins, or is your primary goal to quantify protein abundance and assess differences between conditions? The distinction between qualitative and quantitative proteomics will largely determine the technology and methodology you select for your study.

2.1 Qualitative Proteomics

Qualitative proteomics involves the identification of proteins within a sample and understanding their roles within the context of biological processes. If your goal is to map the protein landscape of a sample, methods like DDA are ideal. DDA facilitates comprehensive protein identification by selecting precursor ions for fragmentation based on their intensity. This method is particularly useful for discovery-based studies, allowing researchers to identify novel proteins or characterizing protein families.

However, DDA is not well-suited for large-scale quantitative analysis due to its stochastic nature and missing data issues. It is best employed when the primary objective is protein identification, while quantitative measurements are secondary.

2.2 Quantitative Proteomics

Quantitative proteomics is employed when measuring the abundance of proteins across different conditions or experimental groups is the focus. Techniques such as DIA, isobaric labeling (TMT/iTRAQ), and label-free quantification are tailored for accurate quantification of proteins. DIA offers reproducible and consistent quantification by fragmenting all ions within predefined m/z windows, which is ideal for large datasets, biomarker discovery, or comparing multiple experimental groups. It is particularly useful for complex samples like plasma, serum, or tissues with high sample variability.

Isobaric labeling (TMT/iTRAQ) allows for multiplexed analysis by tagging peptides from multiple samples with identical chemical labels, enabling simultaneous analysis in a single mass spectrometry run. This approach is cost-effective for high-throughput studies, especially in large-scale biomarker discovery.

For targeted quantification of specific proteins, PRM/SRM are the gold standards. These methods offer high sensitivity and reproducibility, making them particularly valuable for studying protein pathways or validating biomarkers identified in discovery-based studies.

2.3 Sample Size and Throughput Requirements

The number of samples you need to process will influence the method you choose, particularly in terms of throughput and resolution. For small-scale studies, where in-depth analysis of a limited number of samples is the primary goal, DDA or PRM methods are ideal. These techniques provide detailed protein identification and quantification but are more resource-intensive and time-consuming when processing a large number of samples.

In contrast, large-scale studies that involve high-throughput proteomics require methods that can handle many samples simultaneously. DIA and isobaric labeling (TMT/iTRAQ) are particularly well-suited for high-throughput applications, enabling the processing of large numbers of samples without compromising data quality. DIA ensures reproducibility and high precision, while TMT/iTRAQ allows for the efficient comparison of multiple experimental groups in a single run.

For very large-scale studies, especially when focusing on predefined protein sets, non-MS-based technologies such as Olink PEA or SomaScan can be highly effective. These methods offer fast, cost-effective quantification of specific proteins across large cohorts, making them ideal for biomarker discovery and validation studies in clinical research.

3. Choose the Right Proteomics Technology Based on Your Goals and Samples

Choosing the appropriate proteomics technology involves aligning your sample characteristics and research objectives with the strengths and limitations of different methods. Below is a detailed breakdown of various proteomics technologies, the sample types they are best suited for, and their respective advantages and disadvantages.

3.1 Mass Spectrometry-based Proteomics

Mass spectrometry (MS) is the cornerstone of proteomics analysis, offering both qualitative and quantitative data with high sensitivity. The primary MS-based methods used in proteomics are DDA, DIA, and isobaric labeling.

· DDA (Data-Dependent Acquisition):

DDA is a discovery-based approach that identifies as many proteins as possible by selecting ions for fragmentation based on their intensity. This method is ideal for exploring new proteomes or when detailed protein identification is the primary objective. DDA works well with simple samples like cell lines or moderate complexity tissues, but it is not suited for large-scale quantitative analysis due to missing data and variability in ion selection.

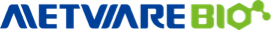

· DIA (Data-Independent Acquisition):

DIA offers a more robust approach for quantitative proteomics. Unlike DDA, which fragments ions based on intensity, DIA fragments all ions within defined m/z windows. This results in consistent and reproducible quantification, making it ideal for complex samples like plasma, serum, or large datasets from cohort studies. DIA provides high-precision data with minimal missing values, making it particularly useful for large-scale biomarker discovery or condition-based studies.

Difference in MS1 isolation windows for the DDA and DIA modes.

Image reproduced from Tian, X., Permentier, H. P., Bischoff, R, 2023, Mass spectrometry reviews, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

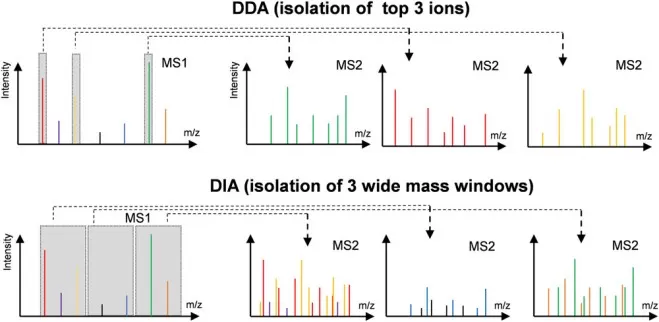

· Isobaric Labeling (TMT/iTRAQ):

TMT and iTRAQ are isobaric tagging methods used for multiplexing, where peptides from different samples are labeled with identical mass tags. These tags allow the simultaneous analysis of multiple samples in a single mass spectrometry run, making them ideal for high-throughput quantitative proteomics. They are particularly useful for comparative studies across different conditions. However, in complex samples like plasma or tissues, co-isolation interference can lead to quantification inaccuracies. As the number of samples increases, the sensitivity and accuracy of these methods may decrease, limiting their applicability for very large-scale studies.

Schematic view of TMT quantitative proteomics strategies.

Image reproduced from Giambruno, R., Mihailovich, M., Bonaldi, T, 2018, Frontiers in molecular biosciences, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

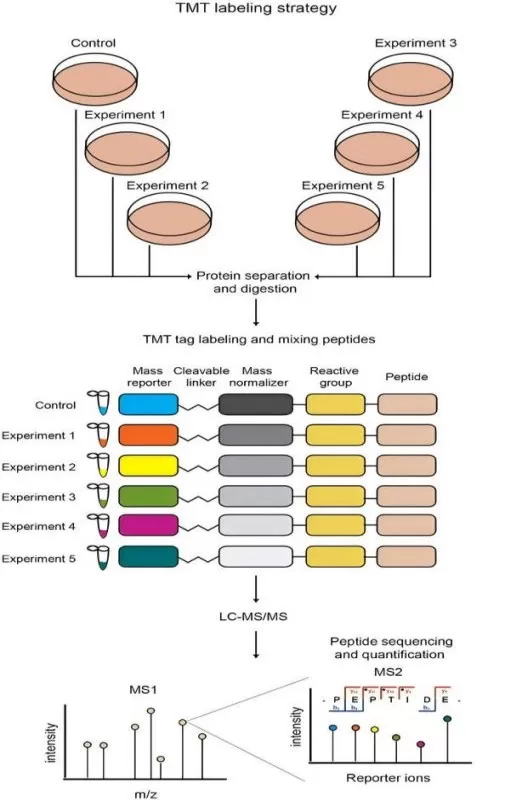

· Targeted Proteomics (PRM/SRM):

For studies focusing on specific proteins or biomarkers, PRM (Parallel Reaction Monitoring) and SRM (Selected Reaction Monitoring) are the most appropriate methods. These techniques provide highly reproducible and precise quantification of predefined proteins. They are particularly useful for biomarker validation and pathway studies. PRM/SRM are also well-suited for low-input samples, such as rare biopsies or single cells, as they allow targeted analysis of specific proteins with minimal sample material.

Schematic Comparison of SRM and PRM Techniques for Targeted Quantitative Proteomics.

Image reproduced from Toghi Eshghi, S., Auger, P., Mathews, W. R., 2018, Clinical Proteomics, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

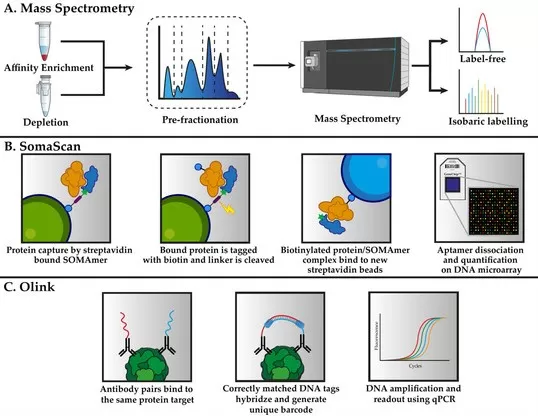

3.2 Non-MS-based Proteomics

Non-MS technologies like Olink PEA and SomaScan provide alternative approaches for proteomics, offering high-throughput capabilities and focusing on specific protein sets.

· Olink PEA (Proximity Extension Assay):

Olink PEA is a highly sensitive method that utilizes antibody pairs linked to DNA oligos. When the antibodies bind to the same target protein, the oligos are extended, producing a quantifiable signal. This approach allows for the simultaneous measurement of up to hundreds of proteins, making it ideal for clinical biomarker discovery and large-scale cohort studies. However, Olink PEA is not suitable for discovery-based studies as it is limited to predefined protein panels.

· SomaScan:

SomaScan employs SOMAmers (modified aptamers) that bind specific proteins for simultaneous analysis of up to 1,300 proteins. This platform is particularly useful for large-scale proteomic studies, especially when examining a predefined set of proteins. Like Olink PEA, SomaScan is limited by the proteins included in its library and cannot identify novel proteins outside that set.

Comparison of Quantitative Proteomics Technologies: Mass Spectrometry, SomaScan, and Olink.

Image reproduced from Palstrøm, N. B., Matthiesen, R., Rasmussen et al., 2022, Biomedicines, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

4. Common Scenarios and Recommended Pathways

4.1 Clinical Biomarker Discovery in Plasma

Plasma proteomics is inherently challenging due to the extreme dynamic range of protein concentrations. High-abundance proteins such as albumin and immunoglobulins can mask the detection of low-abundance biomarkers, which are often crucial for disease diagnosis. To address this, protein depletion is used to remove the abundant proteins, followed by DIA for comprehensive profiling of low-abundance proteins. For validation of biomarkers, PRM/SRM is employed to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the identified biomarkers. In large-scale studies, SomaScan can be used for high-throughput analysis of predefined proteins, allowing for efficient screening across large patient cohorts.

4.2 Signaling Pathway Mechanism Study

When investigating cellular signaling pathways, particularly those involving post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation), it is essential to enrich for phosphoproteins. Phosphopeptide enrichment techniques, such as IMAC or TiO₂, are employed to isolate modified proteins. Following enrichment, high-resolution LC-MS/MS is used to identify phosphorylation sites and map the signaling networks. Functional validation techniques, such as Western blotting, are crucial for confirming the biological significance of the observed phosphorylation events and their impact on cellular functions.

4.3 Drug Target Identification

In drug discovery, identifying potential drug targets is critical. Chemical proteomics methods, such as affinity purification-MS, are used to isolate protein-drug complexes and identify interacting proteins. Once potential targets are identified, PRM/SRM is employed for targeted validation of the interactions between the drug and its targets. This approach enables precise quantification of protein-drug interactions and facilitates the discovery of drug targets involved in specific cellular processes.

Reference

1. Tian, X., Permentier, H. P., & Bischoff, R. (2023). Chemical isotope labeling for quantitative proteomics. Mass spectrometry reviews, 42(2), 546–576. https://doi.org/10.1002/mas.21709

2. Giambruno, R., Mihailovich, M., & Bonaldi, T. (2018). Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics to Unveil the Non-coding RNA World. Frontiers in molecular biosciences, 5, 90. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2018.00090

3. Toghi Eshghi, S., Auger, P., & Mathews, W. R. (2018). Quality assessment and interference detection in targeted mass spectrometry data using machine learning. Clinical proteomics, 15, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-018-9209-x

4. Palstrøm, N. B., Matthiesen, R., Rasmussen, L. M., & Beck, H. C. (2022). Recent Developments in Clinical Plasma Proteomics-Applied to Cardiovascular Research. Biomedicines, 10(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10010162

5. Aebersold, R., & Mann, M. (2016). Mass-spectrometric exploration of proteome structure and function. Nature, 537(7620), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature19949

6. Geyer, P. E., Kulak, N. A., Pichler, G., Holdt, L. M., Teupser, D., & Mann, M. (2016). Plasma Proteome Profiling to Assess Human Health and Disease. Cell systems, 2(3), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2016.02.015

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.