Integrated Proteomics and Metabolomics: Building an Optimal Multi-Omics Strategy

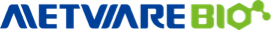

In the post-genomic era, single-omics studies (only genomics, only transcriptomics, only proteomics, or only metabolomics) are often not enough to explain complex phenotypes such as cancer progression, immune–metabolic disorders, plant stress responses, or fruit quality traits.

Integrating proteomics with metabolomics within a multi-omics framework allows researchers to connect molecular mechanisms to observable phenotypes in a causal, systems-level way. By jointly interrogating proteins and metabolites, integrated proteomics and metabolomics can reveal pathway activity, regulatory bottlenecks, and biomarkers that are invisible to any single data layer.

In this blog, we focus on how to design and execute integrated proteomics–metabolomics projects, covering:

- The biological rationale for integrating proteomics and metabolomics

- The main analytical platforms for metabolomics and proteomics (with comparison tables)

- A step-by-step multi-omics workflow from study design to data integration

- Application cases in human disease and plant research

- Practical tips and FAQs for planning multi-omics projects with a service provider

Why Integrate Proteomics and Metabolomics?

Biological systems follow a tightly connected information chain: Genome → Transcriptome → Proteome → Metabolome → Phenotype

Proteomics characterizes the full complement of proteins in a biological system, including abundance, post-translational modifications (PTMs), subcellular localization, and interaction networks. In other words, it answers “who is doing the work, and how?”.

Metabolomics profiles small-molecule metabolites that represent the ultimate biochemical outputs of gene and protein activity. Because metabolites sit closest to the phenotype, they are highly sensitive to environment, diet, drugs, and disease state.

Integrating proteomics and metabolomics:

- Links enzyme abundance or modification state to changes in pathway flux (for example, glycolysis, TCA cycle, kynurenine pathway, lipid metabolism).

- Helps distinguish cause versus consequence: is a metabolite shift driven by a specific enzyme, upstream signaling, or external exposures?

- Increases power for biomarker discovery, mechanism-of-action studies, and patient or line stratification compared with any single-omics layer alone.

In short, integrated proteomics–metabolomics workflows enable researchers to connect protein function to metabolic outputs and phenotypes in a more mechanistic, multi-omics way.

Figure 1. From Genotype to Phenotype: The Value of Integrating Proteomics and Metabolomics

Core Analytical Platforms for Metabolomics and Proteomics

Choosing the right analytical platform is the foundation of a successful multi-omics integration strategy. Below we summarize commonly used metabolomics and proteomics technologies and their typical strengths and limitations.

Table 1. Overview of Main Metabolomics Platforms

|

Technology |

Typical vendor platforms |

Key strengths |

Main limitations |

|

LC–MS (Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry) |

Orbitrap, Q-TOF, triple quadrupole systems |

• High sensitivity for a broad range of polar and non-polar metabolites • Simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analysis • Dominant platform for untargeted metabolomics, targeted metabolomics, and lipidomics |

• Metabolite databases and spectral libraries are still incomplete • Structural isomers can be difficult to distinguish without MS/MS and authentic standards |

|

GC–MS (Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry) |

Typical GC–MS systems from major vendors |

• Excellent chromatographic resolution and reproducibility • Mature EI spectral libraries enabling high-confidence identification • Ideal for volatile and derivatizable metabolites (organic acids, amino acids, sugars) |

• Requires derivatization and more complex sample preparation • Biased toward volatile, thermally stable compounds; less suitable for labile lipids or large polar metabolites |

|

NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) |

High-field NMR instruments |

• Inherently quantitative and non-destructive • Minimal sample preparation • Good for distinguishing structural isomers and elucidating structures |

• Lower sensitivity and dynamic range than MS-based methods • Typically lower metabolite coverage; often used for targeted or fingerprinting applications |

In practice, LC–MS-based metabolomics (using reversed-phase LC for lipids and HILIC for polar metabolites) is widely adopted in clinical metabolomics, plant metabolomics, and food metabolomics. GC–MS and NMR serve as complementary platforms for specific questions. (Learn more at: LC-MS VS GC-MS: What's the Difference)

Table 2. Common Quantitative Proteomics Strategies

|

Strategy |

Data acquisition mode |

Key strengths |

Main limitations |

|

Isobaric tag–based quantification (e.g., TMT) |

DDA (Data-Dependent Acquisition) |

• High multiplexing (many samples per run) • Accurate relative quantification with good reproducibility • Suitable for controlled, same-species, same-tissue comparisons |

• Not ideal for presence/absence detection of very low-abundance proteins • Ratio compression and more complex workflows • Higher reagent and instrument costs |

|

DIA proteomics (Data-Independent Acquisition; e.g., 4D-DIA, microDIA) |

DIA |

• Very high proteome coverage and reproducibility • Well suited for large cohorts and clinical proteomics • More robust to missing values across batches |

• Requires specialized software and computing resources • Often relies on spectral libraries or advanced library-free algorithms |

|

Label-free quantification (LFQ) |

DDA |

• Widely used and cost-effective • Flexible for variable sample numbers; no labeling required |

• Lower quantitative accuracy and reproducibility than isobaric tags or optimized DIA • More sensitive to batch effects and LC–MS variability |

For integrated proteomics–metabolomics projects, LC–MS-based metabolomics paired with DIA-based quantitative proteomics often provides an optimal balance between depth, reproducibility, and scalability within a multi-omics study design. (Learn more at: DIA Proteomics vs DDA Proteomics: A Comprehensive Comparison)

Step-by-Step Workflow for Integrated Proteomics–Metabolomics Projects

A successful multi-omics project is not just about adding more assays. It requires coordinated design across the entire workflow, from biological question to validation.

Figure 2. End-to-End Multi-Omics Study Design Combining Proteomics and Metabolomics

Step 1 – Define Clear Biological Questions and Study Design

Begin with precise biological questions that match your system and phenotype of interest. In biomedical research, you may ask which protein–metabolite signatures predict the onset of inflammatory bowel disease or diabetic nephropathy, or how a drug candidate reshapes signaling pathways and downstream metabolism. In plant and agricultural research, key questions often include which proteins and metabolites drive drought tolerance, disease resistance, or fruit flavor and aroma, and how light, temperature, or UV-B treatments alter secondary metabolite pathways.

Key design principles:

- Choose biologically meaningful comparison groups (cases vs controls, treated vs untreated, resistant vs susceptible lines, different time points, etc.).

- Use sufficient biological replicates across both proteomics and metabolomics.

- Minimize confounders (age, sex, environment, diet, growth conditions, time of sampling).

- Plan sample randomization and blocking to reduce technical bias.

Step 2 – Sample Collection, Preparation, and Quality Control

Different sample types (serum, plasma, tissue, FFPE, plant leaves, fruit, cell pellets, microbial cultures) require optimized extraction protocols for proteins and metabolites.

For proteomics, ensure adequate protein yield and quality. For standard quantitative proteomics, workflows often target at least tens of micrograms of total protein per sample. When protein input is limited (for example, 2–30 μg), micro-input DIA workflows (such as 4D-microDIA) can still achieve good proteome coverage with carefully optimized methods.

For metabolomics, rapidly quench metabolism (e.g., snap-freezing, cold solvents) to capture a true snapshot. Use consistent extraction solvents and protocols across all samples. Include pooled QC samples, blanks, and (if possible) internal standards.

Quality control metrics such as retention time stability, mass accuracy, peak shapes, identification rates, and missing value rates are essential to ensure data quality before multi-omics data integration.

Step 3 – Omics Data Acquisition and Pre-Processing

Proteomics workflow (for example, DIA):

- Protein extraction, reduction, alkylation, and tryptic digestion.

- LC–MS/MS acquisition with appropriate gradients, MS resolution, and DIA window schemes.

- Database searching using a high-quality species-specific protein database (such as UniProt). For non-model organisms, transcriptome-derived protein databases or databases from closely related species may be used when necessary, but performance is typically lower.

Metabolomics workflow:

- Untargeted LC–MS or GC–MS to profile thousands of metabolite features.

- Optional targeted panels for specific pathways (such as the kynurenine pathway, TCA cycle, amino acid metabolism, one-carbon metabolism).

- Peak picking, alignment, normalization, and metabolite identification/annotation using in-house and public libraries.

- After pre-processing, you obtain protein intensity matrices and metabolite abundance matrices, ready for integrated proteomics–metabolomics analysis.

Step 4 – Proteomics and Metabolomics Data Integration

Common multi-omics integration approaches include:

Unsupervised integration

Joint dimensionality reduction (e.g., multi-block PCA, multi-block PLS, MOFA) on combined proteome–metabolome matrices to reveal shared variation and co-regulated protein–metabolite modules.

Supervised integration for phenotype prediction

Multi-omics PLS-DA, random forests, elastic nets, or deep learning models that use proteins and metabolites together to classify disease vs control, responder vs non-responder, or high- vs low-quality lines, helping identify multi-omic biomarkers with stronger effect sizes than single-omics markers.

Pathway- and network-based integration

Mapping proteins and metabolites to KEGG, Reactome, and other pathway databases to visualize coordinated shifts in entire pathways, and building protein–metabolite interaction networks to identify key hubs (for example, rate-limiting enzymes, central metabolites).

The choice of methods depends on sample size, biological question, and data structure, but the goal is always to connect molecular changes across layers in a mechanistic way.

Step 5 – Molecular Validation and Functional Experiments

Multi-omics analyses generate hypotheses; experimental validation confirms biological relevance:

Proteomics validation: Western blotting, PRM/MRM assays, functional assays such as knockdown, knockout, or overexpression.

Metabolomics validation: targeted LC–MS quantification of selected metabolites.

Mechanistic follow-up: genetic or pharmacological perturbation of candidate pathways, dietary interventions, or stress treatments.

Application Case 1 – Integrated Proteomics–Metabolomics Signatures in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

A large nested case–control study in population cohorts has shown that plasma proteomics can reveal preclinical signatures of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) years before diagnosis. Hundreds of plasma proteins were profiled across tens of thousands of participants, and a multi-protein signature predicting Crohn’s disease many years before clinical onset was identified, capturing immune activation and early gut barrier changes. Such proteomic signatures highlight how circulating proteins can act as sensitive sentinels of subclinical disease activity and risk.

Within an integrated proteomics–metabolomics framework, these immune- and barrier-related proteins can be linked to metabolites reflecting microbiome activity and host metabolic state, such as bile acids, microbial metabolites, and oxidative stress markers. Combining proteomics and metabolomics into multi-omics risk models is expected to improve both sensitivity and specificity for IBD prediction and monitoring compared with single-omics markers alone, and may support earlier intervention and stratified patient management.

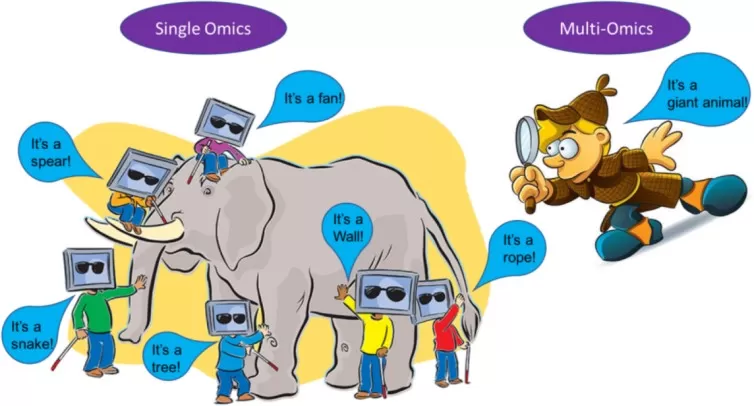

Application Case 2 – Maternal High-Fat Diet, Immune–Metabolic Crosstalk, and Offspring Neurodevelopment

Maternal high-fat diet (mHFD) is known to induce maternal immune activation (MIA), which can disrupt fetal brain development. Recent work has begun to reveal the underlying immune–metabolic mechanisms that connect maternal diet to long-term neurobehavioral outcomes. In experimental models, mHFD elevates lipopolysaccharide and inflammatory cytokines, triggering MIA and reshaping tryptophan metabolism. This shift drives the kynurenine pathway toward neurotoxic metabolites that accumulate in the embryonic brain, induce oxidative stress, impair neuronal migration, and ultimately lead to social behavioral deficits in offspring. Interventions that reduce immune activation, modulate the kynurenine pathway, or supplement antioxidants such as N-acetylcysteine can partially rescue these effects, highlighting tractable mechanistic nodes.

In an ideal integrated proteomics–metabolomics study, proteomics would quantify cytokines, signaling proteins, and synaptic proteins across maternal serum, placenta, and fetal brain, while metabolomics simultaneously measures tryptophan, kynurenine, downstream metabolites, glutathione, and oxidative stress markers. Joint integration of these datasets would help identify immune–metabolic modules linking maternal diet, inflammation, and neurodevelopment, and could prioritize candidate pathways for therapeutic modulation.

Figure 3. Maternal High-Fat Diet–Induced Maternal Immune Activation and Kynurenine Pathway Dysregulation in Fetal Brain

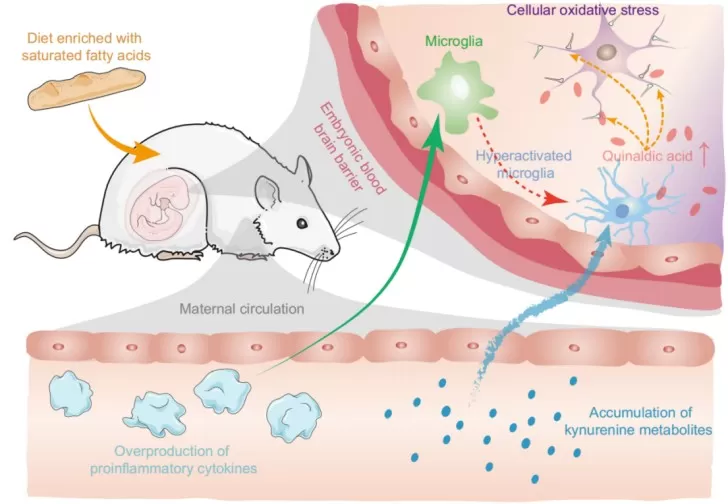

Application Case 3 – Multi-Omics Decoding of Fruit Aroma Under UV-B in Peach

In plant science, integrating proteomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics is highly effective for dissecting secondary metabolism and quality traits. A recent study on detached peach fruit under UV-B irradiation illustrates how a multi-omics approach can uncover regulatory modules controlling aroma. UV-B irradiation significantly decreases levels of the monoterpene linalool, a key aroma compound in peach. Multi-omics analysis identified PpMADS2, a MADS-box transcription factor, as a central regulator that activates the terpene synthase gene PpTPS1 to promote linalool biosynthesis. Under UV-B, the E3 ubiquitin ligase PpCOP1 ubiquitinates PpMADS2 and triggers its degradation, which suppresses PpTPS1 expression and linalool production.

Overexpression of PpMADS2 in peach and tomato fruits increases linalool levels, functionally confirming its regulatory role. By aligning proteome changes (PpMADS2, PpCOP1) with metabolome changes (linalool and related volatiles) and transcriptome data for terpene pathway genes, this integrated proteomics–metabolomics–transcriptomics strategy provides a coherent mechanistic model for how UV-B reshapes fruit aroma.

Figure 4. UV-B–Triggered PpCOP1–PpMADS2–PpTPS1 Module Controlling Linalool Biosynthesis in Peach Fruit

Practical Design Tips for Integrated Proteomics–Metabolomics Projects

When planning a project with a service provider such as MetwareBio, consider the following practical points.

Cohort and batch design

Avoid splitting a single proteomics experiment into multiple, widely separated batches whenever possible, as batch effects can seriously compromise quantitative comparisons.

If batching is unavoidable, use consistent protocols, shared control samples, and statistical batch-correction methods. (Learn more at: Metabolomics Batch Effects and Transcriptomics batch effects)

Sample amount and platform choice

Confirm expected protein and metabolite yields for each sample type in advance.

If protein input is limited, ask whether micro-input DIA workflows are available.

For metabolomics, ensure sufficient volume or tissue for both untargeted and targeted panels.

Database and species support

For proteomics, a curated species-specific database such as UniProt is preferred. (Learn more at: Proteomics Databases)

For non-model organisms, high-quality transcriptome-derived protein databases can be used but may reduce identification depth and specificity.

Downstream deliverables

Clarify what you need from the analysis: differential proteins and metabolites, pathway enrichment, correlation networks, candidate biomarkers, predictive models, and publication-ready figures and tables.

MetwareBio offers integrated proteomics, metabolomics, and multi-omics analysis services, from study design and high-throughput data generation to pathway-level interpretation and report preparation, supporting both biomedical and plant/agricultural research.

FAQs About Proteomics and Metabolomics in Multi-Omics

Q1. Can I send proteomics samples in multiple batches and still analyze them together?

This is generally not recommended. Quantitative proteomics is sensitive to batch effects arising from instrument drift, LC column changes, and reagent lots. Splitting a single study across different batches can distort fold-changes and reduce confidence in differential protein results. If batching is unavoidable, involve your service provider early to design appropriate controls and batch-correction strategies.

Q2. What if my protein amount is too low for standard quantitative proteomics?

First, measure actual protein yield after extraction. As a rough guide:

Above about 30 μg of total protein per sample: standard DIA or label-free workflows are usually suitable.

Between about 2 μg and 30 μg: micro-input DIA workflows can often deliver good performance with optimized sample preparation and LC–MS settings.

Below about 2 μg: the number of reliably quantified proteins will be limited; consider pooling samples, optimizing extraction, or revisiting sampling strategy.

Q3. How do I choose the right protein database for non-model organisms?

Recommended steps:

Use a curated species-specific protein database if available.

If not available, consider a high-quality transcriptome-derived protein database for that species.

As a last resort, use a database from a closely related species.

Remember that transcriptome-derived or related-species databases usually yield fewer identifications and more ambiguous assignments, so they should be treated as temporary solutions.

Q4. Can highly homologous proteins be distinguished by proteomics?

Not always. Shotgun proteomics detects and quantifies peptides, not intact proteins. If two proteins share most or all peptides (high sequence homology), only unique peptides can distinguish them. When unique peptides are absent or below detection, the proteins may appear as a combined protein group in the results.

Conclusion: Turning Proteomics–Metabolomics Integration into Actionable Multi-Omics Insights

Integrated proteomics and metabolomics has become a core strategy in multi-omics research. By connecting protein function with metabolic outputs, integrated studies can:

- Reveal disease mechanisms and early biomarkers before clinical onset

- Illuminate immune–metabolic crosstalk in complex disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, and neurodevelopmental disease

- Decode how environmental cues reshape plant metabolism, yield, and quality traits

With robust study design, appropriate platform choices, advanced multi-omics data integration, and rigorous validation, proteomics–metabolomics integration provides a powerful route to mechanistic insight and actionable biomarkers.

MetwareBio supports researchers across human, animal, and plant systems with end-to-end proteomics and metabolomics services, as well as comprehensive multi-omics data integration and interpretation.

References

- Grännö O, Bergemalm D, Salomon B, et al. Preclinical Protein Signatures of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Nested Case-Control Study Within Large Population-Based Cohorts. Gastroenterology. 2025;168(4):741-753. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2024.11.006

- Wei C, Yang H, Ye B, et al. Ubiquitination of the PpMADS2 transcription factor controls linalool production during UV-B irradiation in detached peach fruit. Plant Physiol. 2025;198(1):kiaf159. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiaf159

- Sun P, Wang M, Chai X, et al. Disruption of tryptophan metabolism by high-fat diet-triggered maternal immune activation promotes social behavioral deficits in male mice. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):2105. Published 2025 Mar 2. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-57414-4

- Wörheide MA, Krumsiek J, Kastenmüller G, Arnold M. Multi-omics integration in biomedical research - A metabolomics-centric review. Anal Chim Acta. 2021;1141:144-162. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2020.10.038

- Pinu FR, Beale DJ, Paten AM, et al. Systems Biology and Multi-Omics Integration: Viewpoints from the Metabolomics Research Community. Metabolites. 2019;9(4):76. Published 2019 Apr 18. doi:10.3390/metabo9040076

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.