From Biomarkers to Mechanisms: How Proteomics Is Reshaping Metabolic Disease Studies

In the few seconds it takes you to read this sentence, millions of protein molecules across your body are orchestrating exquisitely coordinated metabolic processes. Yet when we confront modern epidemics such as type 2 diabetes (T2D) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), we are often observing a systemic breakdown of these protein networks. Heterogeneity is the central challenge: under the same diagnostic label, T2D and NAFLD can arise through distinct biological routes—ranging from predominant insulin resistance to β-cell dysfunction, or from indolent steatosis to rapidly progressive fibrosis. Conventional clinical markers (e.g., HbA1c, fasting glucose, and liver enzymes) rarely capture this complexity, contributing to delayed detection, coarse subtyping, and suboptimal monitoring. Proteomics is changing that. By quantifying thousands of proteins at once, proteomics can move beyond association to illuminate mechanisms, support causal inference, and enable predictive modeling—shifting metabolic disease research from static indicators to dynamic, actionable biology. In this blog, we highlight how technological advances and large-scale population studies are accelerating this transition.

Why Metabolic Diseases Need Proteomics

Metabolic diseases such as T2D and NAFLD share a common limitation: their clinical labels conceal substantial biological diversity. For example, T2D is not a single entity but a spectrum that includes subgroups with distinct etiologies—such as severe insulin resistance versus primary insulin deficiency—each carrying different risks for complications including kidney disease and retinopathy [1]. Similarly, NAFLD encompasses highly variable trajectories: some individuals progress quickly to steatohepatitis (MASH) and fibrosis, while others remain stable for years [2][3]. This diversity reflects dysregulation in protein networks governing glucose homeostasis, lipid handling, and inflammation—networks that routine biomarkers (e.g., HbA1c or ALT) cannot resolve. Clinically, this matters because insufficient molecular resolution can miss high-risk individuals, such as those with isolated impaired glucose tolerance (iIGT) who may not be captured by standard screening strategies [4].

Proteomics addresses this gap by focusing on proteins—the functional effectors of cellular pathways. Compared with genomics (which captures inherited potential) and transcriptomics (which reflects transient gene expression), proteomics more directly reports real-time physiological states, including post-translational modifications (PTMs) that can decisively alter protein function. Recent advances in high-throughput proteomic platforms have pushed the field beyond exploratory discovery and enabled three major shifts:

1. Generalizable risk prediction and stratification: moving from isolated protein associations to validated signatures that identify individuals likely to develop disease or progress.

2. Causal inference and drug-target prioritization: integrating genetics to distinguish causal drivers from correlated bystanders.

3. Near-clinical applications: advancing non-invasive diagnostics and treatment monitoring toward real-world use.

Together, these shifts support earlier intervention by identifying at-risk individuals before overt symptoms and by guiding therapies toward biologically defined subtypes [4][5].

Liver and Metabolic Diseases

Image reproduced from Guilliams et al., 2022, Cell, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Technological Revolution: From “Blind Men Touching an Elephant” to Panoramic Scanning

Proteomics has progressed from fragmented, partial views to increasingly comprehensive “panoramic” measurement, propelled by a growing ecosystem of complementary platforms. This evolution is especially important for metabolic diseases, where interacting pathways and tissue-specific biology mean no single method can capture the full picture. Different technologies offer distinct strengths in depth, breadth, throughput, and biological context.

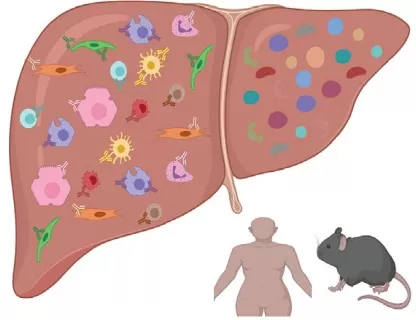

· Mass spectrometry (e.g., DIA/TMT): Mass spectrometry excels in deep mechanistic interrogation, including pathway coverage and PTM mapping (e.g., phosphorylation, acetylation). In T2D, MS-based profiling has revealed how endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress–related proteins such as MAP3K5 contribute to β-cell apoptosis under stress, helping explain how certain genetic variants elevate diabetes risk [6]. PTM sensitivity is also critical in NAFLD: fructose-induced acetylation of CPT1α can reduce fatty acid oxidation in disease models, uncovering regulatory mechanisms not apparent at the abundance level alone [7]. These features make MS particularly valuable for tissue-focused studies where mechanistic resolution is essential.

DIA MS Proteomics

· Proximity extension assay (PEA; e.g., Olink): PEA is optimized for high-throughput measurement with strong technical reproducibility, making it well suited for large cohort studies. For example, in the China Kadoorie Biobank, PEA enabled quantification of 2,923 plasma proteins in ~2,000 participants while minimizing technical variability, supporting robust associations with incident T2D and downstream model development [5]. Such stability is indispensable for risk prediction, where batch effects can otherwise overwhelm biological signals.

· Aptamer-based platforms (e.g., SomaScan): Aptamer technologies provide ultra-broad proteome coverage—often assaying >4,000 proteins—enabling unbiased discovery and multi-protein signatures. In the Cardiovascular Health Study, profiling 4,776 proteins identified 51 novel associations with diabetes risk, including plexin-B2, which has been linked to pancreatic dysfunction [8]. This breadth is especially useful in heterogeneous conditions like NAFLD, where unexpected pathways may carry diagnostic or prognostic value [3].

· Post-translational modification (PTM) profiling: Increasingly routine PTM analyses add a functional layer beyond protein abundance. In NAFLD, acetylome studies showed how fructose upregulates ketohexokinase (KHK-C), reshaping global protein acetylation to promote lipogenesis—insights that may inform therapeutic targeting [7]. Because PTMs can respond rapidly to environment and diet, they provide a powerful readout of dynamic regulation.

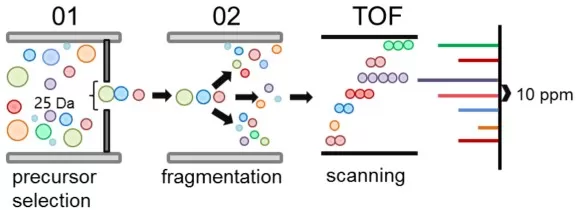

· Single-cell and spatial proteomics: These emerging approaches map proteins within cellular and tissue architecture. In the liver, spatial proteomics integrated with transcriptomics has resolved zonation patterns and cell-type distributions in healthy versus obese states, helping explain regional susceptibility to injury and remodeling [9]. Such methods move beyond bulk averages to reveal where and how proteins act in situ.

Hepatic macrophage populations reside in distinct niches

Image reproduced from Guilliams et al., 2022, Cell, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

These technologies are not merely additive—they are synergistic. Mass spectrometry provides mechanistic depth, PEA offers cohort-scale stability, aptamers enable wide discovery, PTM profiling captures regulation, and spatial methods restore anatomical context. Together, they enable a multi-dimensional view of metabolic disease biology, including how protein networks shift in response to diet and therapy [3][7].

Proteomics for Risk Prediction and Stratification: Who Gets Sick, Who Progresses?

Proteomics is making metabolic disease prediction and progression stratification substantially more precise. This matters because earlier identification can prevent downstream complications—for instance, detecting individuals at high risk of T2D before glucose abnormalities become clinically apparent, or identifying NAFLD patients most likely to progress so that biopsies and intensive surveillance are reserved for those who need them. By capturing network-level dysregulation that single biomarkers miss, proteomics transforms “risk scores” into actionable tools.

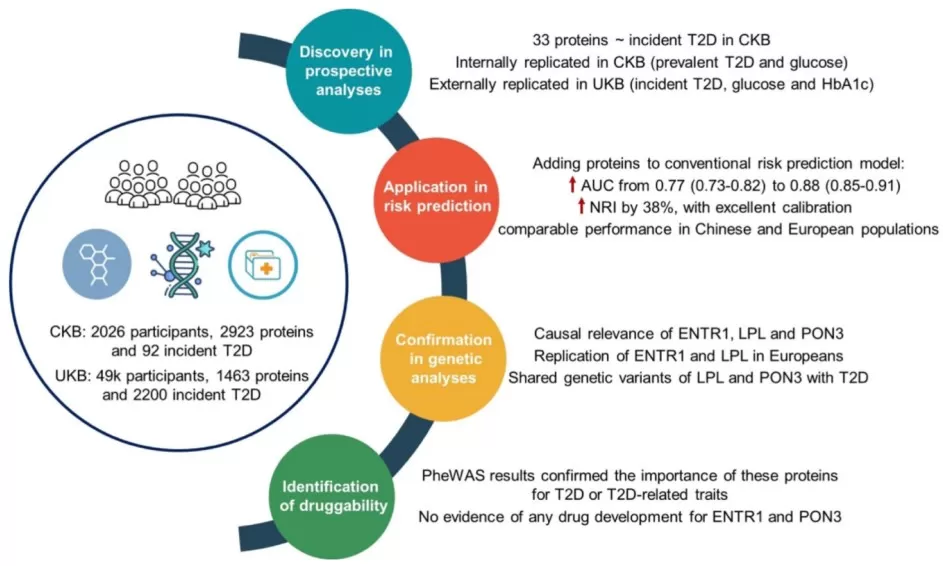

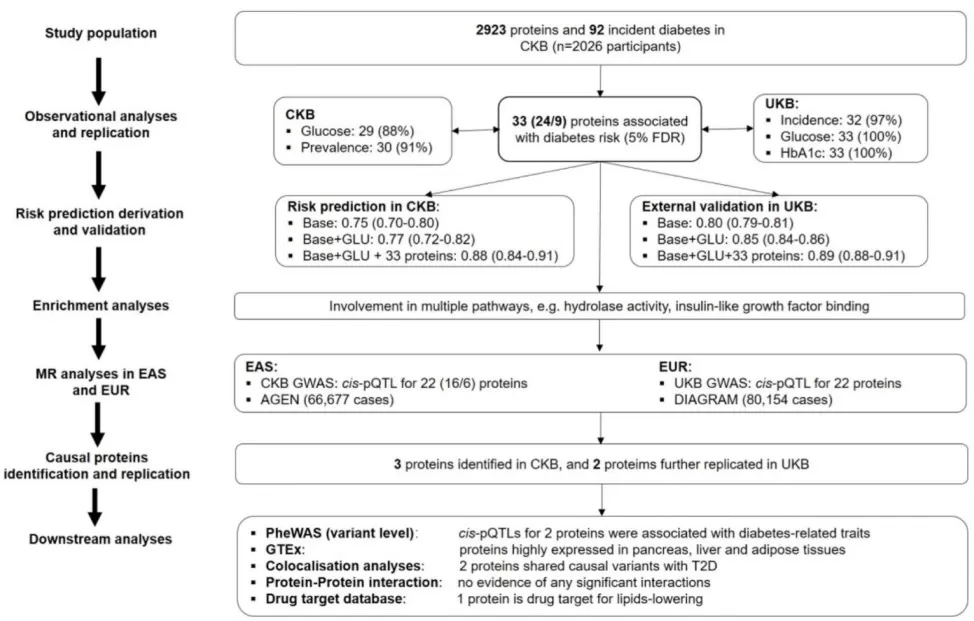

· Diabetes risk prediction: Protein signatures can outperform traditional clinical models. In the China Kadoorie Biobank, adding 33 plasma proteins (e.g., IGFBP1 and GHR) to a standard risk model increased AUC from 0.77 to 0.88 and improved net reclassification by 38%, indicating more accurate identification of high-risk individuals [5]. In the Fenland study, a panel of three proteins (RTN4R, CBPM, GHR) improved detection of iIGT, raising AUROC to 0.80 relative to clinical predictors alone [4]. Such gains are clinically meaningful because they enable earlier lifestyle or pharmacologic interventions for “silent” high-risk states.

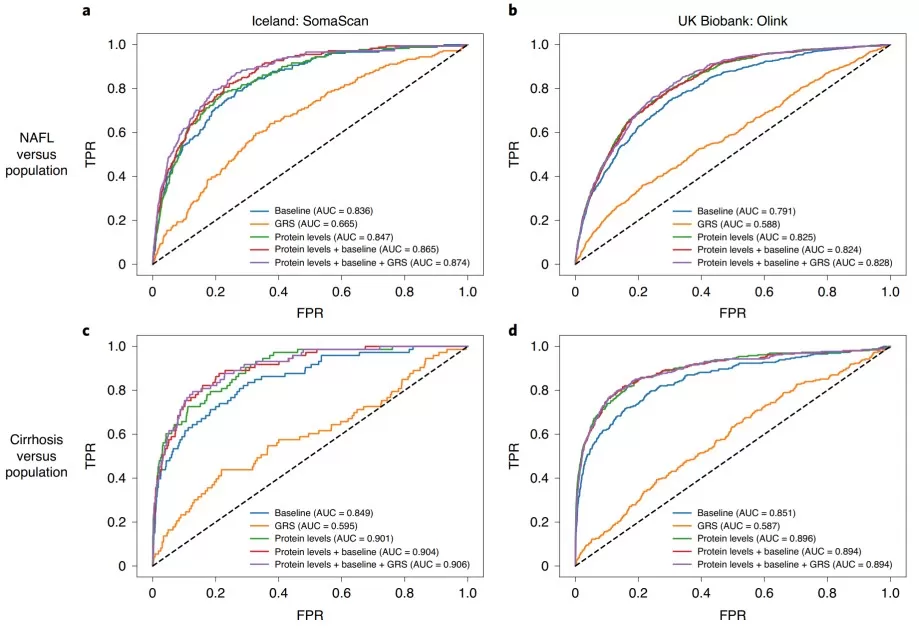

· Molecular stratification for personalized management: Proteomics-based subtyping can better anticipate complication risks than conventional classifications. In the Swedish All New Diabetics cohort, proteomics-informed clustering revealed five T2D subgroups; the subgroup characterized by severe insulin resistance showed higher risk of diabetic kidney disease, whereas the insulin-deficient subgroup was more prone to retinopathy [1]. In NAFLD, multi-protein signatures can distinguish steatosis from advanced fibrosis with AUCs up to 0.92, enabling non-invasive monitoring that may reduce reliance on biopsy [2][3]. Collectively, these results illustrate a shift from one-size-fits-all assessment to precision risk management driven by protein-network biology.

ROC for models trained to discriminate between NAFL and cirrhosis.

Image reproduced from Sveinbjornsson et al., 2022, Nature Genetics, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Mechanism Elucidation and “Causal Protein” Screening: Turning Candidates into Targets

Identifying protein associations is relatively straightforward; demonstrating that a protein is causal—and therefore a credible therapeutic target—is far harder. This challenge has historically limited translation in metabolic research because correlation does not imply mechanism. By integrating proteomics with human genetics, approaches such as Mendelian randomization (MR) and colocalization can strengthen causal inference and prioritize targets with greater confidence.

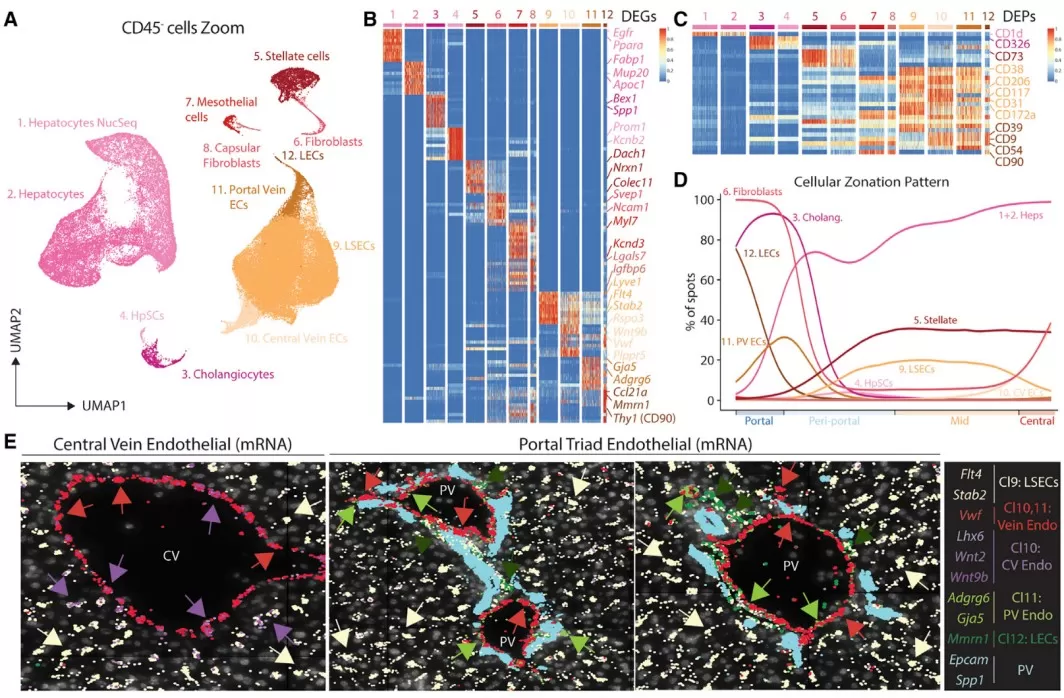

· Causal protein identification: Proteome-wide MR leverages genetic variants as instruments to test whether genetically predicted protein levels influence disease risk. In one analysis of 1,886 plasma proteins, MR implicated 47 proteins as causal for T2D, including HLA-DRA and AGER, which were also linked to microvascular complications [10]. In Chinese cohorts, proteins such as LPL and PON3 showed strong colocalization evidence (e.g., pH4 > 0.6), suggesting shared causal variants affecting both protein levels and T2D risk [5]. Such evidence can elevate candidates like ENTR1 for drug development by reducing the likelihood that associations are driven by confounding [5].

Proteomic analyses in diverse populations improved riskprediction for type 2 diabetes

Image reproduced from Yao et al., 2024, Diabetes Care, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

· Mechanistic pathway resolution: Beyond target prioritization, proteomics can pinpoint dysregulated pathways and mechanistic nodes. For instance, ER stress proteins including MAP3K5 have been linked to β-cell apoptosis, and elevated expression in diabetic islets provides a mechanistic bridge between genetic susceptibility and cellular failure [6]. In NAFLD, proteomic studies have shown that fructose-induced KHK-C can remodel acetylation programs and suppress fatty acid oxidation, with functional validation via knockdown experiments [7]. Proteomics has also implicated complement cascade proteins in diabetic comorbidities, highlighting additional druggable pathways [11]. By connecting association to mechanism, proteomics accelerates mechanism-driven translation and de-risks target selection [5].

Fatty Liver/MASH’s “Liquid Biopsy”: From Biopsy to Blood-Based Models

For NAFLD and MASH, liver biopsy is invasive, costly, and unsuitable for population-scale screening or frequent monitoring. Proteomics offers a compelling alternative: blood-based “liquid biopsy” signatures that can track inflammation and fibrosis non-invasively. This capability can improve patient management and make clinical trials more feasible by enabling repeated, quantitative assessment over time.

Multiple studies demonstrate that protein signatures can diagnose and stage NAFLD with strong performance. For example, panels built on 37 proteins achieved AUCs of 0.85 for fibrosis, 0.79 for steatosis, and 0.83 for ballooning in validation cohorts [3]. Importantly, these signatures include proteins not previously linked to NAFLD, offering insight into lipid metabolism and inflammatory pathways [2][3]. Proteomics can also monitor treatment response: in interventional studies, protein scores shifted significantly with therapies such as pioglitazone or vitamin E, outperforming placebo and mirroring histological improvement [3]. Moreover, KHK-C–related acetylation changes can be detectable in serum and may serve as early indicators of metabolic dysfunction [7]. Taken together, proteomics functions as a dynamic “liquid biopsy” that can guide risk-adapted follow-up and therapy escalation for rapid progressors, while reducing reliance on invasive procedures [3].

Challenges and Next Steps: Bridging the Gap to the Clinic

Despite rapid progress, several barriers must be addressed before proteomics becomes routine in metabolic disease care. These challenges are not peripheral; they directly determine whether proteomic discoveries translate into reproducible, clinically deployable tests.

· Technical and analytical considerations: Batch effects, platform-specific biases, and cohort heterogeneity can compromise reproducibility. Large studies in resources such as the UK Biobank and China Kadoorie Biobank underscore how population genetics and environment influence protein–disease associations, reinforcing the need for large, diverse validation cohorts [5][10][11]. Differences in assay coverage across platforms (e.g., SomaScan vs Olink) also require harmonized protocols and cross-platform benchmarking to ensure signatures generalize [5][8].

Study design and analytic approaches for proteomic analyses of type 2 diabetes population

Image reproduced from Yao et al., 2024, Diabetes Care, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

· Translation and implementation: Cost, interpretability, and regulatory validation remain key constraints. Broad assays can be expensive, motivating the development of smaller, targeted panels (e.g., 3–5 proteins for iIGT detection) that balance affordability with performance [4]. Clinically usable outputs must be interpretable—often distilled into risk scores or staging metrics with clear decision thresholds, as illustrated by NAFLD models with high AUCs [3]. In addition, regulatory pathways require evidence that proteomic tests improve outcomes beyond existing standards, as exemplified by work showing incremental value for peripheral artery disease (PAD) prediction in T2D [12].

· Future directions: Maximizing clinical impact will likely require integrated, multi-omics frameworks. Combining proteomics with genetics and other omics can strengthen causal inference, identify convergent pathways (e.g., complement cascade contributions to T2D comorbidities), and prioritize novel targets such as FAM3D [11]. In parallel, low-cost panels for high-risk T2D and liver fibrosis could enable longitudinal monitoring and treatment adjustment based on proteomic trajectories—supporting a shift from reactive to preventive care [3][7].

These steps are essential if proteomics is to become a cornerstone of precision metabolic medicine.

Conclusion: A New Lens on Metabolic Health

Proteomics is more than a technological upgrade—it is a conceptual shift in how we study and manage metabolic disease. By reframing T2D and NAFLD through the lens of protein networks, we move from isolated measurements (e.g., glucose excursions or liver enzymes) to a systems-level view of dysregulation. Proteomics can reveal mechanisms, support early risk prediction, and enable non-invasive monitoring, as demonstrated by the studies highlighted here. While challenges in cost, standardization, and reproducibility remain, integration with genetics and multi-omics is rapidly advancing causal interpretation and test development. In the near future, routine “proteomic health checks” may help preempt metabolic disease, turning the tide against these growing epidemics. The message is clear: proteins are not only markers—they are gateways to mechanism-driven translation.

References

1. Ahlqvist E, Storm P, Käräjämäki A, Martinell M, Dorkhan M, Carlsson A, Vikman P, Prasad RB, Aly DM, Almgren P, et al. Novel subgroups of adult-onset diabetes and their association with outcomes: a data-driven cluster analysis of six variables. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 May;6(5):361-369. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30051-2.

2. Sveinbjornsson G, Ulfarsson MO, Thorolfsdottir RB, Jonsson BA, Einarsson E, Gunnlaugsson G, Rognvaldsson S, Arnar DO, Baldvinsson M, Bjarnason RG; et al. Multiomics study of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2022 Nov;54(11):1652-1663. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01199-5.

3. Sanyal AJ, Williams SA, Lavine JE, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Alexander L, Ostroff R, Biegel H, Kowdley KV, Chalasani N, Dasarathy S, Diehl AM, Loomba R, Hameed B, Behling C, Kleiner DE, Karpen SJ, Williams J, Jia Y, Yates KP, Tonascia J. Defining the serum proteomic signature of hepatic steatosis, inflammation, ballooning and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2023 Apr;78(4):693-703. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.11.029.

4. Carrasco-Zanini J, Pietzner M, Lindbohm JV, Wheeler E, Oerton E, Kerrison N, Simpson M, Westacott M, Drolet D, Kivimaki M, Ostroff R, Williams SA, Wareham NJ, Langenberg C. Proteomic signatures for identification of impaired glucose tolerance. Nat Med. 2022 Nov;28(11):2293-2300. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02055-z.

5. Yao P, Iona A, Pozarickij A, Said S, Wright N, Lin K, Millwood I, Fry H, Kartsonaki C, Mazidi M, Chen Y, Bragg F, Liu B, Yang L, Liu J, Avery D, Schmidt D, Sun D, Pei P, Lv J, Yu C, Hill M, Bennett D, Walters R, Li L, Clarke R, Du H, Chen Z; China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group. Proteomic Analyses in Diverse Populations Improved Risk Prediction and Identified New Drug Targets for Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2024 Jun 1;47(6):1012-1019. doi: 10.2337/dc23-2145.

6. Sokolowski EK, Kursawe R, Selvam V, Bhuiyan RM, Thibodeau A, Zhao C, Spracklen CN, Ucar D, Stitzel ML. Multi-omic human pancreatic islet endoplasmic reticulum and cytokine stress response mapping provides type 2 diabetes genetic insights. Cell Metab. 2024 Nov 5;36(11):2468-2488.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2024.09.006.

7. Helsley RN, Park SH, Vekaria HJ, Sullivan PG, Conroy LR, Sun RC, Romero MDM, Herrero L, Bons J, King CD, Rose J, Meyer JG, Schilling B, Kahn CR, Softic S. Ketohexokinase-C regulates global protein acetylation to decrease carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a-mediated fatty acid oxidation. J Hepatol. 2023 Jul;79(1):25-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.02.010.

8. Cronjé HT, Mi MY, Austin TR, Biggs ML, Siscovick DS, Lemaitre RN, Psaty BM, Tracy RP, Djoussé L, Kizer JR, Ix JH, Rao P, Robbins JM, Barber JL, Sarzynski MA, Clish CB, Bouchard C, Mukamal KJ, Gerszten RE, Jensen MK. Plasma Proteomic Risk Markers of Incident Type 2 Diabetes Reflect Physiologically Distinct Components of Glucose-Insulin Homeostasis. Diabetes. 2023 May 1;72(5):666-673. doi: 10.2337/db22-0628.

9. Guilliams M, Bonnardel J, Haest B, Vanderborght B, Wagner C, Remmerie A, Bujko A, Martens L, Thoné T, Browaeys R, et al. Spatial proteogenomics reveals distinct and evolutionarily conserved hepatic macrophage niches. Cell. 2022 Jan 20;185(2):379-396.e38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.018.

10. Yuan S, Xu F, Li X, Chen J, Zheng J, Mantzoros CS, Larsson SC. Plasma proteins and onset of type 2 diabetes and diabetic complications: Proteome-wide Mendelian randomization and colocalization analyses. Cell Rep Med. 2023 Sep 19;4(9):101174. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101174.

11. Loesch DP, Garg M, Matelska D, Vitsios D, Jiang X, Ritchie SC, Sun BB, Runz H, Whelan CD, Holman RR, Mentz RJ, Moura FA, Wiviott SD, Sabatine MS, Udler MS, Gause-Nilsson IA, Petrovski S, Oscarsson J, Nag A, Paul DS, Inouye M. Identification of plasma proteomic markers underlying polygenic risk of type 2 diabetes and related comorbidities. Nat Commun. 2025 Mar 3;16(1):2124. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-56695-z.

12. Yu H, Zhang J, Qian F, Yao P, Xu K, Wu P, Li R, Qiu Z, Li R, Zhu K, Li L, Geng T, Yu X, Li D, Liao Y, Pan A, Liu G. Large-Scale Plasma Proteomics Improves Prediction of Peripheral Artery Disease in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2025 Mar 1;48(3):381-389. doi: 10.2337/dc24-1696.

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.