Bottom-Up Proteomics Guide: Principles, Workflows, and LC–MS/MS Applications

Bottom-up proteomics has become the workhorse strategy of mass spectrometry–based proteomics, often referred to as shotgun proteomics. By digesting complex protein mixtures into peptides and analyzing them with high-resolution LC–MS/MS, researchers can identify and quantify thousands of proteins from plasma, tissues, cells, and even single cells in a single experiment.

This article walks through the key principles, standard workflows, data acquisition modes, and real-world applications of bottom-up proteomics, and serves as a practical guide for researchers planning LC–MS/MS-based experiments or considering outsourcing to specialized proteomics service providers such as MetwareBio.

From Genomics to Proteomics: Why Mass Spectrometry–Based Bottom-Up Proteomics?

Genomics and transcriptomics describe what could be expressed in a cell, but proteins are the actual executors of biological function. Their abundance, localization, and post-translational modifications (PTMs) change dynamically in response to environment, disease, or drug treatment. These changes are often invisible at the DNA level, which is why proteomics has become essential for understanding disease mechanisms, signaling pathways, and therapeutic response.

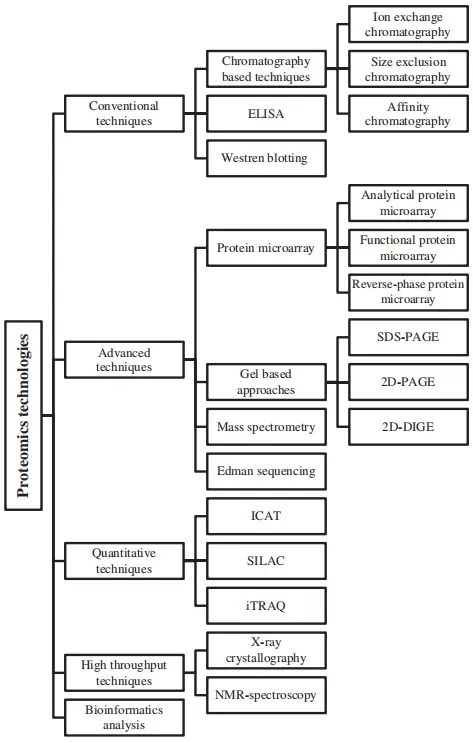

Over the past two decades, a broad toolkit of proteomics technologies has emerged. Conventional approaches include chromatography-based separation, ELISA, and Western blotting (learn more at: ELISA vs. Western Blot). Advanced methods add protein microarrays, gel-based techniques such as SDS–PAGE and 2D-PAGE, and, crucially, mass spectrometry–based proteomics. Among MS-driven strategies, bottom-up LC–MS/MS currently offers the best combination of depth, sensitivity, and throughput for complex biological samples.

Figure 1. Overview of proteomics technologies from conventional methods to advanced mass spectrometry–based approaches.

What Is Bottom-Up Proteomics (Shotgun Proteomics)?

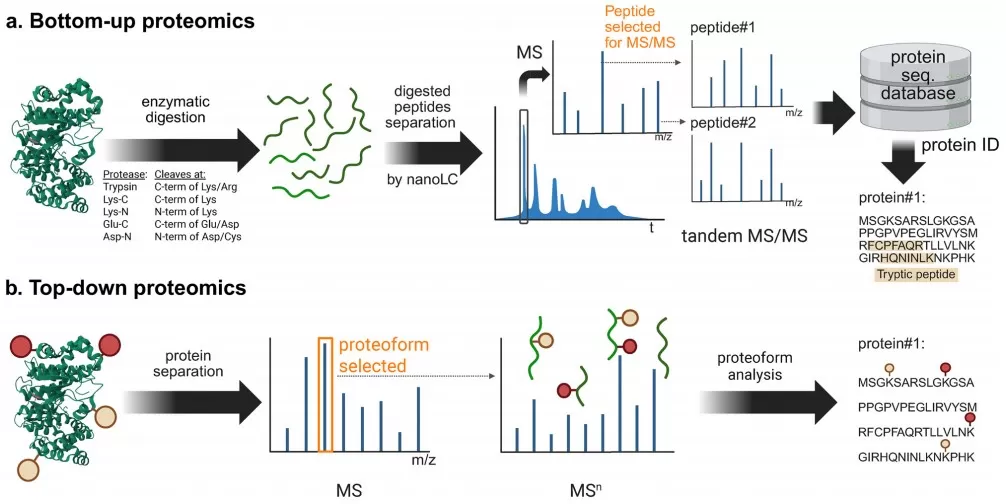

In bottom-up proteomics, proteins from a biological matrix—plasma, serum, tissue, cultured cells, or microbial communities—are first extracted and denatured. They are then reduced, alkylated, and digested with sequence-specific proteases, most commonly trypsin and Lys-C, to generate a complex mixture of peptides. After desalting and cleanup, peptides are separated by nano-flow reversed-phase liquid chromatography (nanoLC) and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). Database search algorithms match acquired MS/MS spectra to theoretical spectra generated from protein sequence databases, thereby identifying peptides and inferring the underlying proteins.

Because peptides are easier to separate and ionize than intact proteins, this bottom-up strategy enables deep coverage of low-abundance proteins and diverse PTMs. It is compatible with label-free quantification, isobaric labeling (TMT, iTRAQ), SILAC, and targeted proteomics such as PRM, making it highly versatile for both discovery and hypothesis-driven studies. (learn more at: Label-based Protein Quantification Technology—iTRAQ, TMT, SILAC)

Core Workflow of Bottom-Up Proteomics by LC–MS/MS

Although the exact protocol depends on sample type and instrument platform, most bottom-up LC–MS/MS experiments follow three main stages: sample preparation, LC–MS/MS data acquisition, and computational analysis.

Sample Collection, Protein Extraction, and Depletion

Sample preparation converts the biological specimen into a high-quality peptide mixture. In plasma and serum proteomics, a major challenge is the extreme dynamic range of protein concentrations: a few high-abundance proteins (albumin, immunoglobulins, transferrin, etc.) dominate the signal and can obscure lower-abundance biomarkers.

To address this, many workflows employ nanoparticle- or magnetic bead–based depletion and enrichment. Nano-magnetic beads exploit the formation of a “protein corona” and the Vroman effect to preferentially bind low-abundance proteins while reducing high-abundance components. Such strategies can significantly increase identification depth in blood-based proteomics and are widely used in clinical biomarker discovery.

For other sample types, proteins are typically extracted in a harsh denaturing buffer, clarified by centrifugation, and quantified to ensure consistent protein input across samples.

Reduction, Alkylation, and Enzymatic Digestion

Next, proteins undergo chemical processing to guarantee efficient and reproducible digestion. Disulfide bonds are reduced (for example, with DTT or TCEP), and cysteine residues are alkylated (commonly with iodoacetamide) to prevent re-oxidation. Proteases such as trypsin and Lys-C then cleave proteins into peptides with predictable C-terminal residues and charge states, simplifying database search and quantitative analysis.

After digestion, peptides are desalted using C18 solid-phase extraction to remove salts, detergents, and other contaminants that suppress ionization. The peptide concentration is adjusted to a defined range to allow consistent injection onto the LC–MS system.

Peptide Cleanup and LC Injection

Desalted peptides are dried (for example, by vacuum centrifugation) and reconstituted in a low-organic solvent such as 0.1% formic acid in water. This solution is compatible with reversed-phase nanoLC and promotes efficient loading on the trap column. At this stage, samples are ready for nanoLC–MS/MS analysis.

Figure 2. Comparison of bottom-up and top-down proteomics workflows for LC–MS/MS analysis.

Data Acquisition Strategies in Bottom-Up Proteomics

NanoLC Separation and MS Detection

In modern bottom-up proteomics, nano-flow UHPLC systems are coupled directly to high-resolution mass spectrometers such as Orbitrap-based instruments. Peptides are first trapped and concentrated on a short precolumn and then separated on a long analytical column (e.g., C18 with sub-2-µm particles) using shallow organic gradients. Low nano-flow rates (nL–µL/min) substantially improve electrospray ionization efficiency, sensitivity, and dynamic range.

Eluting peptides are ionized—most commonly by nano-electrospray ionization (nESI)—and enter the mass spectrometer, where both precursor masses (MS1) and fragment ion spectra (MS2) are recorded. Fragmentation is typically achieved by higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) or related CID methods, producing rich b- and y-ion series for confident peptide sequencing.

DDA, DIA, and Targeted PRM

Several acquisition modes are used in bottom-up LC–MS/MS:

- Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) records an MS1 survey scan and then selects the most intense precursor ions for fragmentation in each cycle. DDA is widely used in discovery proteomics and for building spectral libraries, but may suffer from missing values in large cohorts.

- Data-independent acquisition (DIA) divides the m/z range into consecutive isolation windows and fragments all precursors within each window. DIA-MS generates comprehensive and highly reproducible “digital proteome maps” that are particularly attractive for quantitative clinical proteomics and longitudinal studies.

- Parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) is a targeted bottom-up method in which specific peptide precursors are isolated and all their fragment ions are recorded with high resolution. PRM assays are ideal for protein biomarker verification and clinical assay development because they combine high selectivity with excellent sensitivity.

The choice among DDA, DIA, and PRM depends on experimental goals: broad discovery, large-cohort quantification, or targeted validation. (learn more at: Mass Spectrometry Acquisition Mode Showdown: DDA vs. DIA vs. MRM vs. PRM)

Next-Generation Bottom-Up Workflows for Single-Cell Proteomics

Recent advances in instrument sensitivity and chromatographic performance have pushed bottom-up proteomics into the single-cell regime. The Orbitrap Astral mass spectrometer, for example, enables highly sensitive label-free and DIA-based acquisition schemes that can robustly quantify hundreds to more than a thousand proteins from low-input to single-cell samples while maintaining excellent quantitative precision and accuracy. Systematic method surveys on this platform have optimized parameters such as isolation window width, MS2 resolution, and ion injection times specifically for single-cell bottom-up proteomics, providing a practical blueprint for routine high-throughput applications.

In parallel, multiplexed single-cell bottom-up strategies such as SCoPE2 combine TMT or TMTpro isobaric labeling with minimal sample preparation workflows (for example, mPOP) to analyze hundreds of single cells per day on widely available LC–MS/MS systems. These methods routinely quantify more than 1,000 proteins per cell and can scale to thousands of cells per experiment, enabling detailed dissection of tumor heterogeneity, immune cell states, and developmental trajectories at proteome resolution. These emerging single-cell bottom-up workflows point toward the next generation of ultra-sensitive clinical and translational proteomics.

Protein Identification and Quantitative Bottom-Up Proteomics

Database Search and FDR Control

Raw MS data are processed with specialized software that matches experimental MS/MS spectra to theoretical spectra derived from in silico digestion of protein databases such as UniProt or Ensembl. Peptide-spectrum matches are scored and filtered to control the false discovery rate (FDR), typically to 1% at both peptide and protein levels, using target–decoy strategies.

Identified peptides are then assembled into protein groups, considering shared and unique peptides. The result is a list of confidently identified proteins, their observed peptides, and modification sites.

Quantitative Proteomics Strategies

Bottom-up proteomics supports multiple quantitative strategies for comparing protein abundance across samples or conditions:

- Label-free quantification (LFQ) uses MS1 or DIA signal intensities to estimate peptide and protein abundance across runs. It is attractive for large cohorts because it does not require chemical labeling.

- Isobaric labeling (TMT, iTRAQ) chemically tags peptides from different samples with isobaric reagents that generate distinct low-m/z reporter ions upon HCD fragmentation. Multiplexed LC–MS/MS runs can quantify many samples simultaneously, minimizing batch effects and enabling high-throughput clinical studies.

- Metabolic labeling (SILAC) incorporates stable isotope–labeled amino acids into cellular proteins so that light and heavy peptide pairs can be directly compared in a single run, providing highly accurate relative quantification in cell culture systems.

- Targeted SRM/PRM monitors predefined peptide transitions, offering precise and highly sensitive quantification for focused panels of candidate biomarkers or pathway proteins.

Together, these quantitative proteomics approaches make bottom-up LC–MS/MS a powerful tool for differential expression studies, time-course experiments, and drug-response profiling.

Bioinformatics, Quality Control, and Functional Interpretation in Bottom-Up Proteomics

Robust bioinformatics and statistics are essential to convert large bottom-up data sets into biologically meaningful insights.

Proteomics Quality control starts with removing contaminants and low-confidence identifications, inspecting peptide length distributions, missed cleavages, and protein coverage, and ensuring that intensity distributions look comparable across samples. Correlation heatmaps, principal component analysis (PCA), and hierarchical clustering help visualize sample similarity, detect outliers, and evaluate whether biological groups separate as expected.

For differential expression analysis, protein abundance matrices are usually log-transformed and normalized. Statistical tests such as t-tests or ANOVA are then applied, and p-values are corrected for multiple testing using FDR-controlling procedures (for example, Benjamini–Hochberg). This reduces the risk of false positives when thousands of proteins are assessed simultaneously.

To interpret protein lists in a systems biology context, researchers commonly perform:

- Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment, summarizing affected biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components.

- Pathway analysis using KEGG, Reactome, or similar resources to highlight dysregulated signaling and metabolic networks.

- Protein–protein interaction network analysis to identify hubs, modules, and potential drug targets.

(learn more at: GO vs KEGG vs GSEA: How to Choose the Right Enrichment Analysis?)

These layers of analysis connect proteomic changes to disease mechanisms, drug responses, and phenotypic outcomes.

Clinical and Biomedical Applications of Bottom-Up Proteomics

In clinical proteomics, bottom-up LC–MS/MS is used to profile plasma, serum, tissue, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and other biofluids across patient cohorts. The goal is to discover and validate diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, stratify patients, and understand mechanisms of disease.

Recent Examples of DIA-Based Large-Cohort Plasma Proteomics

Several recent studies illustrate how advanced sample preparation and DIA-MS can transform plasma bottom-up proteomics into a deep, large-cohort technology. One “deep mining” strategy combines magnetic covalent organic framework beads that form a protein corona with DIA-MS and DIA-NN-based data analysis to dramatically increase proteome coverage compared with conventional depletion workflows, while still remaining compatible with clinical sample volumes and turnaround times.

Other work has shown that moderate prefractionation coupled with DIA can significantly improve plasma depth in real patient cohorts. For example, a DIA-based workflow applied to plasma from a COVID-19 cohort used simple depletion, fractionation, and three DIA injections per sample to achieve deep coverage in a cost-efficient manner suitable for biomarker discovery. On the instrumentation side, large-cohort performance has been demonstrated on the Orbitrap Astral platform, where workflows profiling approximately 9,000 proteins from human cell lines and around 700 proteins from undepleted plasma at a throughput of about 100 samples per day were maintained over more than 10 consecutive days with excellent reproducibility. These case studies highlight how DIA-based bottom-up proteomics is maturing into a robust technology for clinical and epidemiological plasma proteomics, and they inform how to design scalable DIA workflows for biomarker projects.

Improvements in sample preparation, LC–MS instrumentation, and DIA-MS workflows have dramatically increased the depth and reproducibility of plasma proteomics, enabling detection of subtle changes in low-abundance proteins and PTMs. Applications span oncology, cardiovascular and metabolic disease, neurology, kidney disease, and infectious disease. For example, cancer studies frequently combine label-free or isobaric-tagged bottom-up proteomics with machine-learning models to identify therapy-response signatures and support personalized treatment decisions.

Bottom-up proteomics also underpins modern chemical proteomics and mechanism-of-action studies in drug discovery. A key example is thermal proteome profiling (TPP), which combines the cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) with quantitative LC–MS/MS to read out drug-induced changes in protein thermal stability across the proteome. By measuring soluble protein abundance over a temperature series, TPP can identify both on-target and off-target proteins whose melting behavior is altered by small-molecule binding, without the need for drug derivatization or immobilization. TPP and related MS-CETSA workflows have been widely applied to map drug–protein interactions, protein–metabolite interactions, and even protein–protein complexes in live cells and tissues.

More recently, a precipitate-supported TPP (PSTPP) variant has been introduced to further increase sensitivity and specificity. Instead of analyzing only the soluble fraction, PSTPP quantifies proteins in both supernatant and precipitate fractions at carefully chosen temperatures where substantial precipitation occurs, and then integrates these complementary signals—often with the aid of deep-learning models—distinguish true drug targets from background. These PSTPP workflows have successfully uncovered previously missed drug targets and off-target liabilities in complex lysates, demonstrating how innovative bottom-up LC–MS/MS–based chemoproteomic assays can deconvolute mechanisms of action at proteome scale.

PTM-focused bottom-up workflows—such as phosphoproteomics, glycoproteomics, ubiquitinomics, and acetylomics—provide large-scale maps of dynamic signaling networks. These approaches have yielded key insights into kinase–substrate relationships, immune signaling, and host–pathogen interactions.

Bottom-Up Proteomics in Industrial Biotechnology and Synthetic Biology

Beyond medicine, bottom-up LC–MS/MS proteomics is increasingly important in industrial biotechnology and synthetic biology. Label-free quantitative bottom-up workflows are widely used to compare proteome profiles between wild-type and engineered strains, identify metabolic bottlenecks, and prioritize enzymes for pathway optimization. For example, increasing the expression of key enzymes in the ethanol production pathway (such as alcohol dehydrogenase and upstream glycolytic enzymes) can significantly boost biofuel yields.

Bottom-up proteomics–driven enzyme engineering also evaluates expression levels, stability, and activity of enzyme variants in parallel, accelerating directed evolution campaigns for greener and more efficient biocatalysts. Emerging single-cell and ultra-low-input proteomics workflows further enable high-resolution mapping of cell-state heterogeneity in microbial communities and mammalian production cell lines, providing actionable insight for bioprocess control and strain selection.

Bottom-Up vs Top-Down: Complementary Proteomics Strategies

Despite rapid advances in top-down proteomics, which analyzes intact proteoforms directly, bottom-up LC–MS/MS remains the primary strategy for large-scale proteome characterization. Bottom-up workflows deliver higher proteome coverage in complex samples, are more tolerant of sample variability, and integrate seamlessly with DIA-MS, multiplexed TMT labeling, and automated sample preparation pipelines. (learn more at: Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Proteomics)

Top-down methods excel when detailed information about specific proteoforms and combinatorial PTMs is required, particularly for relatively simple protein mixtures or purified targets. In practice, many research programs adopt a hybrid strategy: bottom-up proteomics for broad discovery and quantification, complemented by top-down or middle-down workflows for in-depth characterization of selected proteins.

Conclusion: Bottom-Up Proteomics as a Core LC–MS/MS Strategy

Bottom-up proteomics has transformed how we study proteins in health, disease, and engineered biological systems. By integrating robust sample preparation, sensitive nanoLC–MS/MS, flexible acquisition modes such as DDA, DIA-MS, and PRM, and powerful bioinformatics pipelines for quantitative proteomics and functional analysis, researchers can now profile thousands of proteins and PTMs across large sample cohorts with high confidence.

As LC–MS instrumentation, single-cell workflows, and AI-driven data analysis continue to improve, bottom-up proteomics will remain a central pillar of systems biology, clinical proteomics, and industrial biotechnology, turning complex proteomes into actionable molecular insights.

For research teams that prefer to focus on biological questions rather than instrument maintenance, specialized providers such as MetwareBio offer end-to-end bottom-up proteomics services—from sample preparation and nanoLC–MS/MS data acquisition to comprehensive bioinformatics and biological interpretation—helping accelerate discovery and translation.

FAQs About Bottom-Up Proteomics

Q1. What is the main difference between bottom-up and top-down proteomics?

Bottom-up proteomics digests proteins into peptides before LC–MS/MS analysis and then infers proteins from the identified peptides. Top-down proteomics, in contrast, analyzes intact proteoforms directly. Bottom-up offers higher depth and throughput for complex samples, whereas top-down preserves full proteoform information but is currently more technically demanding and lower throughput.

Q2. When should I choose DIA instead of DDA in a bottom-up workflow?

DDA is well suited for discovery studies and building spectral libraries, but it can suffer from missing values in large cohorts. DIA systematically fragments all precursors across the m/z range, generating highly reproducible “digital proteome maps.” For quantitative clinical proteomics, longitudinal studies, and large sample sets, DIA-MS is often the preferred choice.

Q3. Which sample types are suitable for bottom-up proteomics?

Bottom-up LC–MS/MS can be applied to a wide range of samples, including plasma and serum, fresh or FFPE tissues, cultured cells, body fluids such as CSF or urine, as well as microbial communities and bioprocess samples. The key is to adapt the sample preparation protocol—especially lysis, depletion, and digestion—to the specific matrix.

References

- Dupree EJ, Jayathirtha M, Yorkey H, Mihasan M, Petre BA, Darie CC. A Critical Review of Bottom-Up Proteomics: The Good, the Bad, and the Future of this Field. Proteomes. 2020;8(3):14. Published 2020 Jul 6. doi:10.3390/proteomes8030014

- Jiang Y, Rex DAB, Schuster D, et al. Comprehensive Overview of Bottom-Up Proteomics Using Mass Spectrometry. ACS Meas Sci Au. 2024;4(4):338-417. Published 2024 Jun 4. doi:10.1021/acsmeasuresciau.3c00068

- Kowalczyk T, Ciborowski M, Kisluk J, Kretowski A, Barbas C. Mass spectrometry based proteomics and metabolomics in personalized oncology. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(5):165690. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165690

- Krasny L, Huang PH. Data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) for proteomic applications in oncology. Mol Omics. 2021;17(1):29-42. doi:10.1039/d0mo00072h

- Nakayasu ES, Gritsenko M, Piehowski PD, et al. Tutorial: best practices and considerations for mass-spectrometry-based protein biomarker discovery and validation. Nat Protoc. 2021;16(8):3737-3760. doi:10.1038/s41596-021-00566-6

- Zhu Y. Plasma/Serum Proteomics based on Mass Spectrometry. Protein Pept Lett. 2024;31(3):192-208. doi:10.2174/0109298665286952240212053723

- Fröhlich K, Fahrner M, Brombacher E, et al. Data-Independent Acquisition: A Milestone and Prospect in Clinical Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2024;23(8):100800. doi:10.1016/j.mcpro.2024.100800

- Meissner, F., Geddes-McAlister, J., Mann, M. et al. The emerging role of mass spectrometry-based proteomics in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 21, 637–654 (2022). doi.org/10.1038/s41573-022-00409-3

- Petelski AA, Emmott E, Leduc A, et al. Multiplexed single-cell proteomics using SCoPE2. Nat Protoc. 2021;16(12):5398-5425. doi:10.1038/s41596-021-00616-z

- Petrosius V, Aragon-Fernandez P, Arrey TN, et al. Quantitative Label-Free Single-Cell Proteomics on the Orbitrap Astral MS. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2025;24(6):100982. doi:10.1016/j.mcpro.2025.100982

- Wang J, Xie W, Sun L, et al. Establishment and clinical application evaluations of a deep mining strategy of plasma proteomics based on nanomaterial protein coronas. Anal Chim Acta. 2023;1275:341569. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2023.341569

- Ward B, Pyr Dit Ruys S, Balligand JL, et al. Deep Plasma Proteomics with Data-Independent Acquisition: Clinical Study Protocol Optimization with a COVID-19 Cohort. J Proteome Res. 2024;23(9):3806-3822. doi:10.1021/acs.jproteome.4c00104

- Mateus A, Kurzawa N, Becher I, et al. Thermal proteome profiling for interrogating protein interactions. Mol Syst Biol. 2020;16(3):e9232. doi:10.15252/msb.20199232

- Ruan C, Ning W, Liu Z, et al. Precipitate-Supported Thermal Proteome Profiling Coupled with Deep Learning for Comprehensive Screening of Drug Target Proteins. ACS Chem Biol. 2022;17(1):252-262. doi:10.1021/acschembio.1c00936

- Kurzawa N, Leo IR, Stahl M, et al. Deep thermal profiling for detection of functional proteoform groups. Nat Chem Biol. 2023;19(8):962-971. doi:10.1038/s41589-023-01284-8

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.