Quantitative Proteomics: Pioneering Techniques and Future Directions

1. What is Quantitative Proteomics?

Proteomics is the comprehensive study of the entire set of proteins expressed within a biological system—whether cells, tissues, or organisms—under specific conditions. This field goes beyond simple identification by also investigating protein functions, interactions, modifications, and regulation. Unlike genomics or transcriptomics, which focus on genetic blueprints or RNA molecules, proteomics offers a snapshot of the active molecular state within a cell or organism.

Quantitative proteomics is focused on precisely measuring protein abundance and its dynamic changes across different biological states. This approach allows researchers to link molecular dynamics with cellular function, physiological conditions, and disease progression. Unlike traditional methods that merely catalog proteins, quantitative proteomics goes a step further by quantifying protein amounts, providing a deeper understanding of how these levels shift under various conditions. In quantitative proteomics, the primary objective is to measure protein abundance—how much of each protein is present in a sample. This is achieved through two key approaches: relative quantification, which compares protein levels between different conditions (e.g., treated vs. untreated), and absolute quantification, which determines the exact amount of protein in a sample. These measurements allow researchers to explore differential protein expression, identify biomarkers, and study biological processes in a quantifiable manner.

2. Key Technologies in Quantitative Proteomics

Quantitative proteomics has revolutionized our ability to measure protein abundance and its dynamic changes across different biological states. The most common techniques used in quantitative proteomics include mass spectrometry (MS), isotope labeling, label-free quantification (LFQ), and targeted approaches like SRM/PRM. However, recent advancements in affinity-based proteomic platforms such as Olink and SomaScan have introduced new methods that offer high-throughput, high-sensitivity protein quantification, enabling more comprehensive proteomic analyses. These methods are becoming increasingly valuable for large-scale studies, including biomarker discovery and clinical applications.

2.1 Isotope Label-Based Quantification

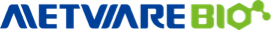

Isotopic labeling techniques, such as SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture) and TMT/iTRAQ (Tandem Mass Tags/Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantification), are widely used in quantitative proteomics to provide precise and reproducible comparisons of protein abundance across experimental conditions. These techniques involve incorporating stable isotopes or chemical tags into peptides, enabling relative quantification by comparing mass differences between labeled and unlabeled peptides.

SILAC involves the incorporation of heavy isotopes of amino acids into proteins during cell culture. After labeling, the light and heavy peptides are mixed, analyzed by MS, and their relative abundance is determined based on the ratio of light to heavy ions. This method is particularly useful for studying dynamic processes such as cell signaling and disease progression in controlled in vitro systems.

In contrast, TMT and iTRAQ use isobaric tags, which allow multiple samples to be analyzed simultaneously in a single mass spectrometry run. These tags have identical mass precursors but release distinct reporter ions during fragmentation. The reporter ions can then be quantified to determine protein abundance across different samples. This method is especially valuable for high-throughput proteomics studies, including biomarker discovery and clinical research, where large sets of samples need to be analyzed rapidly and efficiently.

A comparison of detection methods used in quantitative proteomics.

Image reproduced from Yang, X. L., Shi, Y., Zhang, D. D. et al., 2021, Molecular Therapy Oncolytics, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

2.2 Label-Free Quantification (LFQ)

Label-free quantification (LFQ) methods provide an alternative to isotopic labeling by directly measuring peptide signal intensities or spectral counts in the mass spectrometer. These methods are highly suitable for high-throughput studies, particularly when working with large sample sets. LFQ is cost-effective and eliminates the need for labeling reagents, making it ideal for comparative proteomics across multiple conditions.

A notable label-free technique is Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) using LC-MS/MS, which represents a significant advancement in label-free proteomics. DIA enables the systematic fragmentation of all precursor ions in a sample, providing a comprehensive and unbiased view of the proteome. Unlike traditional Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA), which fragments only the most abundant peptides, DIA captures every detectable peptide, enhancing proteome coverage and quantification reliability. This method is particularly useful for large-scale clinical proteomics and high-throughput studies, as it offers robust reproducibility and requires fewer sample preparations than isotope-based methods.

In LFQ workflows, quantification is based on peptide signal intensities or spectral counts, where higher intensity corresponds to greater protein abundance. While LFQ is less sensitive than isotope-labeling methods, it offers significant advantages in terms of cost-effectiveness and scalability, especially for experiments with many samples. However, its sensitivity for detecting low-abundance proteins may be lower, and the reproducibility of data can be influenced by factors such as ion suppression and sample complexity.

2.3 Targeted Quantitative Proteomics (SRM/PRM)

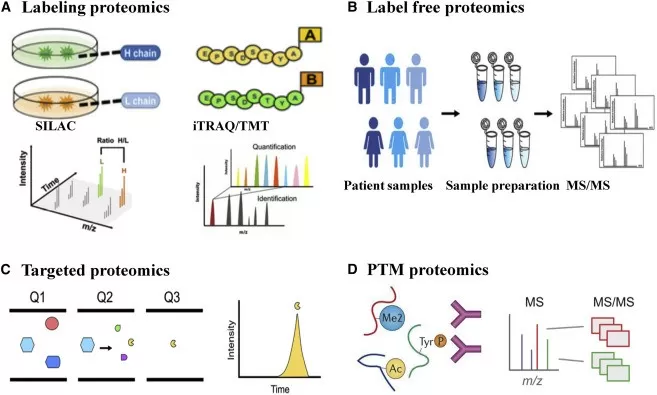

Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) and Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) are targeted proteomics techniques that enable highly specific and sensitive quantification of particular peptides. These methods are especially valuable for validating biomarkers or studying low-abundance proteins. By focusing on pre-selected peptides, SRM and PRM provide precise measurements, making them indispensable tools for clinical proteomics and biomarker validation.

Schematic Comparison of SRM and PRM Techniques for Targeted Quantitative Proteomics.

Image reproduced from Toghi Eshghi, S., Auger, P., Mathews, W. R., 2018, Clinical Proteomics, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

2.4 Emerging Technologies: Olink and SomaScan

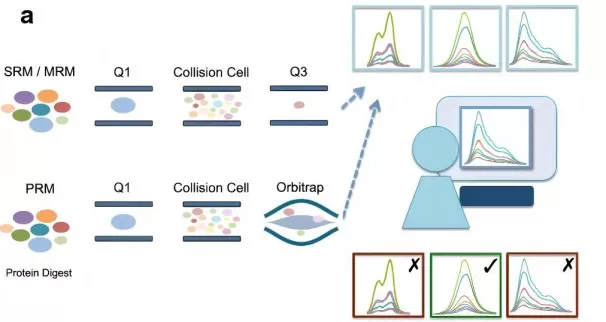

In addition to traditional proteomic techniques, recent developments in high-throughput, affinity-based proteomics platforms such as Olink and SomaScan have greatly expanded the capabilities of quantitative proteomics, especially in large-scale studies. These technologies utilize unique principles and provide substantial advantages in protein quantification, especially for clinical and epidemiological research.

Comparison of Quantitative Proteomics Technologies: Mass Spectrometry, SomaScan, and Olink.

Image reproduced from Palstrøm, N. B., Matthiesen, R., Rasmussen et al., 2022, Biomedicines, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

Olink leverages the Proximity Extension Assay (PEA), a highly sensitive and specific method for measuring protein abundance. In PEA, a pair of antibodies conjugated with unique DNA tags are used to bind to a target protein. When both antibodies bind the same protein, the DNA tags come into close proximity, allowing a polymerase extension to occur and generate a quantifiable DNA signal. This method provides high multiplexing capabilities (with panels measuring up to 92 proteins simultaneously) and is particularly advantageous for profiling proteins in small sample volumes. Its high sensitivity allows the detection of low-abundance proteins, making it an ideal tool for clinical biomarker discovery and personalized medicine.

SomaScan, developed by SomaLogic, is based on SOMAmer reagents—synthetic aptamers that bind to target proteins with high specificity and affinity. These aptamers are selected through a process called SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment). Once bound to a target protein, the aptamers are quantified through fluorescence or other readouts, offering ultra-high multiplexing capability (detecting up to 7,000–11,000 proteins simultaneously). SomaScan is especially valuable in large cohort studies due to its high sensitivity and wide dynamic range, making it an excellent tool for clinical research and disease monitoring.

Unlike traditional targeted proteomics methods such as SRM/PRM, which focus on the precise quantification of pre-selected proteins, Olink and SomaScan provide high-throughput proteomic quantification across hundreds or thousands of proteins in a single assay. These technologies leverage affinity-based assays (PEA for Olink and aptamers for SomaScan) to enable multiplex protein analysis, offering several distinct advantages in quantification: High sensitivity and specificity, broad multiplexing capability, high scalability and throughput. These platforms are often used in conjunction with large population reference datasets, which provide robust data for comparative analyses. This ensures that the results are not only scientifically valid but also translatable across different patient populations. By integrating Olink and SomaScan into quantitative proteomic workflows, researchers can achieve a higher level of multiplexing and sensitivity, making them powerful tools for clinical applications, biomarker discovery, and large-scale proteomic studies.

3. Detailed Workflow of Quantitative Proteomics

Quantitative proteomics is a multi-step process that involves careful planning, precise sample preparation, and high-throughput data analysis. Below is a detailed breakdown of the typical proteomic workflow:

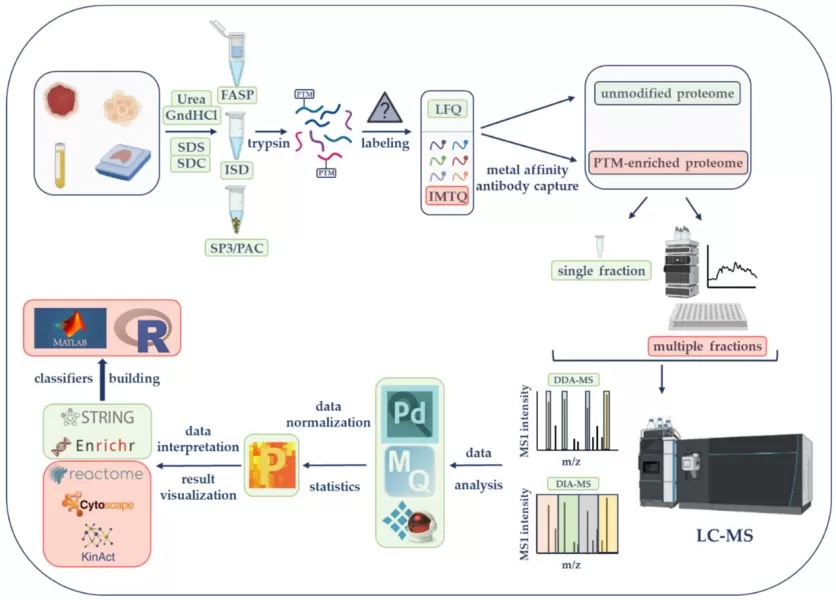

General Workflow of a Quantitative Proteomics Experiment.

Image reproduced from Carrillo-Rodriguez, Selheim, and Hernandez-Valladares, 2023, Cancers, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

3.1 Experimental Design and Sample Collection

A well-designed experimental setup is crucial for generating meaningful proteomic data. Key considerations include the selection of sample groups and biological replicates. It is recommended to use at least three biological replicates per condition to ensure statistical reliability. Additionally, minimizing technical variation by randomizing sample collection and controlling batch effects is essential for reproducibility.

Once the experimental design is established, samples such as tissues, biofluids (e.g., plasma, serum), or cultured cells are collected and preserved, often through cryopreservation to prevent protein degradation.

3.2 Protein Extraction and Quantification

After sample collection, proteins are extracted using optimized lysis buffers containing detergents and protease inhibitors to maintain protein integrity. Protein concentrations are then measured using assays like BCA or Bradford to ensure equal loading for subsequent analysis.

3.3 Protein Digestion

Proteins are enzymatically digested, commonly using trypsin, which cleaves proteins into smaller peptides suitable for mass spectrometry. The digestion conditions—including enzyme-to-substrate ratios, incubation time, and temperature—must be carefully optimized for each sample type. After digestion, peptides are typically purified through solid-phase extraction (SPE) or reverse-phase HPLC to remove contaminants that may interfere with mass spectrometry analysis.

(Learn more at: A Comprehensive Guide to Protein Digestion and Desalting)

3.4 Labeling and Quantitation Preparation

Depending on the experimental strategy:

- Label-Free: Samples are analyzed individually, with quantification based on signal intensities or spectral counts.

- SILAC: Cells are metabolically labeled with heavy isotopes before protein extraction.

- Isobaric Tags (TMT/iTRAQ): Peptides are chemically tagged after digestion and pooled for analysis.

3.5 Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

In this step, peptides are separated using nano-liquid chromatography and analyzed by mass spectrometry. High-resolution instruments like Orbitrap and Q-TOF are often used for their sensitivity and precision, enabling accurate peptide detection and quantification. During the MS1 scan, precursor ions are detected, and in the MS/MS fragmentation step, peptide sequences are derived from fragment ions.

3.6 Data Processing and Protein Identification

Raw data from MS analysis is processed using bioinformatics tools like MaxQuant, Mascot, or Sequest, which compare the spectra to protein databases like UniProt to identify peptides and proteins in the sample. Protein abundance is quantified by measuring peak intensities or reporter ion signals in labeled techniques such as TMT.

3.7 Statistical, Biological Analysis, Validation, and Visualization

Once quantification is complete, statistical methods like t-tests or ANOVA are used to identify differential protein expression across conditions. Biological interpretation is enhanced by functional annotation and pathway analysis, often integrating data from Gene Ontology (GO) or KEGG pathways.

For validation, techniques such as Western blotting, ELISA, or targeted mass spectrometry (SRM/PRM) are commonly used to independently confirm protein abundance. The findings are often cross-referenced with transcriptomic or metabolomic data to explore pathway enrichment or gene-protein interactions.

Data visualization is a key step in proteomics analysis, as it helps transform complex quantitative data into clear, interpretable insights. The visual tools, including volcano plots and network diagrams, are essential for distilling complex data into understandable formats. They play a critical role in summarizing proteomics findings, making them accessible not only to researchers but also to clinicians, thus facilitating the interpretation and application of proteomics data in both scientific and clinical contexts.

4. Challenges and Future Directions in Quantitative Proteomics

Quantitative proteomics has revolutionized our ability to understand complex biological systems, but several technical and conceptual challenges still need to be addressed. These include the complexities of data analysis, issues with sensitivity for low-abundance proteins, variability in reproducibility, and the integration of advanced technologies. Overcoming these challenges will not only improve the accuracy and scope of proteomic analysis but also accelerate its application in clinical diagnostics, drug discovery, and personalized medicine.

4.1 Overcoming Data Complexity and Improving Analysis

High-throughput proteomic technologies, such as mass spectrometry, generate enormous amounts of data that are often complex and difficult to interpret. The need for advanced computational tools to handle this complexity is critical. Additionally, integrating data from multiple studies and platforms requires standardized protocols to ensure consistency and reproducibility. Future progress in bioinformatics, machine learning algorithms, and data processing will be key to improving data analysis efficiency, allowing researchers to extract meaningful biological insights from vast proteomic datasets.

4.2 Enhancing Sensitivity for Low-Abundance Proteins

The detection of low-abundance proteins remains a significant challenge in proteomics, particularly for proteins that play critical roles in diseases like cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. These proteins are often present at levels too low for traditional proteomic techniques to detect accurately. Advances in mass spectrometry sensitivity, as well as the development of new enrichment strategies and data-independent acquisition (DIA) techniques, are essential to address this issue. Improving sample preparation and using novel affinity-based approaches will further enhance the ability to detect low-abundance biomarkers and expand proteomics' clinical applications.

4.3 Ensuring Reproducibility and Standardizing Workflows

Reproducibility remains a key issue for the widespread adoption of proteomics, particularly across different laboratories and experimental conditions. Variations in sample handling, instrument calibration, and data analysis techniques can lead to discrepancies in results. Standardizing workflows from sample collection to data analysis is critical to ensuring consistent and reliable outcomes. The creation of universally accepted reference materials and quality control measures will help address this challenge, enabling more accurate comparisons across studies and fostering greater confidence in proteomic results, especially in clinical and diagnostic settings.

4.4 Integrating AI and Multi-Omics Approaches for Deeper Insights

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) with proteomics is poised to revolutionize protein identification and quantification, enabling more accurate biological interpretations. By leveraging AI algorithms to analyze and interpret complex proteomic data, researchers can enhance the precision of their findings and accelerate discovery. Furthermore, combining proteomics with other omics technologies—such as genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics—will provide a holistic understanding of biological systems. Multi-omics integration, powered by AI, will allow for a more comprehensive exploration of disease mechanisms and pave the way for more personalized and effective treatments.

Reference:

1. Yang, X. L., Shi, Y., Zhang, D. D., Xin, R., Deng, J., Wu, T. M., Wang, H. M., Wang, P. Y., Liu, J. B., Li, W., Ma, Y. S., & Fu, D. (2021). Quantitative proteomics characterization of cancer biomarkers and treatment. Molecular therapy oncolytics, 21, 255–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2021.04.006

2. Toghi Eshghi, S., Auger, P., & Mathews, W. R. (2018). Quality assessment and interference detection in targeted mass spectrometry data using machine learning. Clinical proteomics, 15, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-018-9209-x

3. Palstrøm, N. B., Matthiesen, R., Rasmussen, L. M., & Beck, H. C. (2022). Recent Developments in Clinical Plasma Proteomics-Applied to Cardiovascular Research. Biomedicines, 10(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10010162

4. Carrillo-Rodriguez, P., Selheim, F., & Hernandez-Valladares, M. (2023). Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics Workflows in Cancer Research: The Relevance of Choosing the Right Steps. Cancers, 15(2), 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15020555

Next-Generation Omics Solutions:

Proteomics & Metabolomics

Ready to get started? Submit your inquiry or contact us at support-global@metwarebio.com.